Abusive, Cartoonish, Obscene: How Kara Walker Painted Trump’s America

Revolting.

That is the word black American assemblage artist Betye Saar used in 1997 to describe the work of Kara Walker. At the time, Walker was known primarily for two things: her use of paper cutouts and her propensity for twisting history’s darkest moments into sick jokes. The two distinguishing characteristics collide in her graphic tableaux of the antebellum South, where the brutal horrors of slavery come out to play. From a distance, Walker’s silhouettes resemble children’s book illustrations, which makes the inevitable realization ― that the figures are engaged in lynching, raping, beating and vomiting ― all the more vile.

Walker’s figures aren’t quite people but archetypes, caricatures, myths and fantasies, many of which were cooked up in the imaginations of white supremacists. Some black women are depicted naked, their splayed bodies reading feral and oversexed, while white women wear hoop skirts and bonnets, pictures of Southern civility even when holding someone’s severed head in their gloved hands.

Saar argued Walker’s propagation of racist stereotypes and warping of unspeakable horrors into crude jokes did more harm than good. “The trend today is to be as nasty as you want to be,” she wrote in the International Review of African American Art. “The goal is to be rich and famous. There is no personal integrity.”

It has been 20 years since Saar condemned Walker’s work for being too ugly, too crass, too attention-seeking. Today, rich and famous Donald Trump is president of the United States, leading a White House that romanticizes the Confederacy and sympathizes with white supremacists. The commander in chief’s disturbing, circus-like rule serves as the perfect backdrop for Walker’s current exhibition, itself a nightmarish carnival of racially charged hostility. The exhibition of collaged drawings, paintings and silhouettes Walker made during the summer of 2017 is currently on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co in New York City. Now, Walker’s twisted fantasies feel more like premonitions.

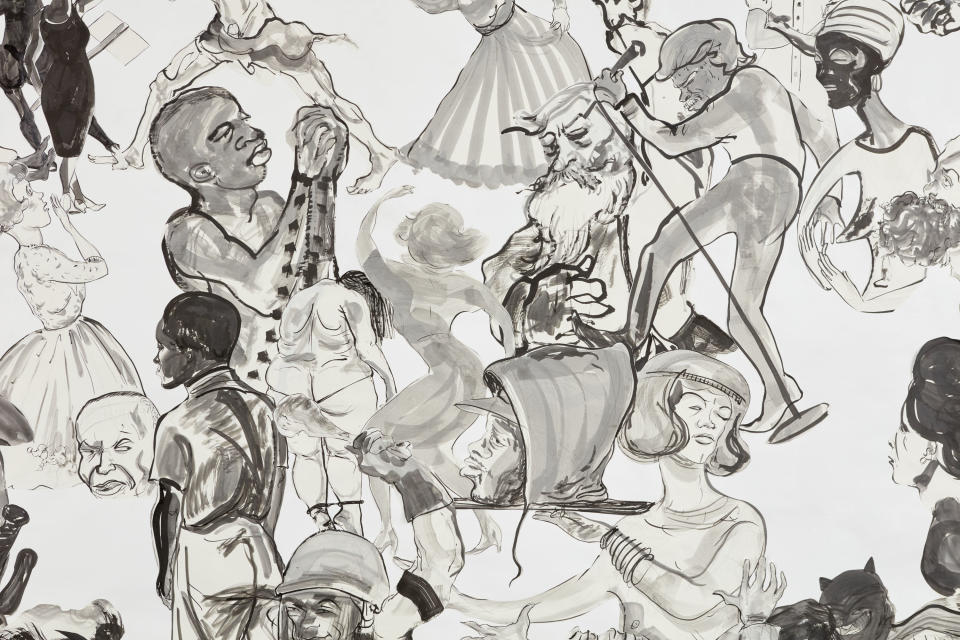

The centerpiece of Walker’s show is the massive 11-by-18-foot collage “Christ’s Entry into Journalism.” Riffing off “Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem,” the piece is teeming with Sumi ink drawings depicting figures real and imagined, past and present, from James Brown to Martin Luther King, Jr., Donald Trump to Frederick Douglass.

Rendered in shades of gray, the Honoré Daumier-like drawings converge on the canvas like a fantastical rally. A cop in riot gear strikes a black man with one hand and films it on his iPhone with the other. A white woman tenders forth Trayvon Martin’s decapitated head, still wearing a hoodie. In the background, a man hangs limp from a tree branch, a noose around his neck, as two women swing trapeze-style on either side of him. A Confederate flag, an American flag, a Nazi salute. Two white men in powder wigs compare penis sizes. A man resembling Trump pokes out from between the legs of a man in a KKK robe, tongue out, shitting on the floor.

Walker’s masterpiece feeds off the logic of legends, nightmares and clichés, carefully arranged through suspicion, paranoia and twisted pleasure. In some unavoidable ways the painting’s composition resembles Trump’s twitter feed. The biting caricatures mirror Trump’s references to public figures slighted by belittling nicknames. Walker’s conjuring of knotted up histories recalls Trump’s habit of presenting bigoted historical falsehoods as facts. The jokey nature of the swampy gathering alludes to Trump’s common defense: that his most loathsome comments, memes and jabs are made in jest.

Walker’s work envisions a mangled American nightmare that felt at a certain time, to some, excessive in its barbarity, dangerous in its dredging up of racism’s dead and buried ghosts. Yet as Hilton Als wrote in a 2007 review of Walker’s work, “slavery is a nightmare from which no American has yet awakened,” and Trump’s inability to condemn white supremacy makes that statement abundantly clear. In 2017 Walker’s satire is not so far-fetched and reckless; it bears a striking resemblance to our reality.

Walker’s images never exist purely in one time or place. The collage “The Pool Party of Sardanapalus (after Delacroix, Kienholz)” adopts the styles of 18th century artist Eugène Delacroix and 20th century Edward Kienholz while still alluding to current events. As Roberta Smith noted in The New York Times, the image depicts a battalion of black women in bathing suits, perhaps a reference to a black teenage girl who was tackled by a white male police officer at a pool party in 2015.

This constant conflation of here and there, now and then, communicates the undead grip racism and misogyny hold on our country. As Walker said in her press release: “How many ways can a person say racism is the real bread and butter of our American mythology ...”

Walker’s cut-outs and collages not only mix up history’s axes, but its players, as well, muddling victims and oppressors in a universally shameful chaos of degradation. Viewers aren’t just encouraged to gaze upon white cruelty and black suffering; instead, they too become complicit in warped memories of historical narratives, rendered from the perspective of the black female artist scouring the mind of the white supremacist.

The act of visiting the gallery contributes to these feelings of discomfort and disgust, too. It’s understandably a disjointed experience to enter a pristine gallery filled mostly with affluent New York collectors to mull over such scathing, bloodthirsty images. “How much is the grave robber one?” an older white woman asked a gallerist during our visit. “What about the little boy being stabbed?” No doubt some of these grisly works will end up on the walls of at least one rich, white collector’s brownstone.

These contradictory and sometimes nauseating aspects of the art world only seem to pique Walker’s interest. A press release promoting her new show went viral for its unusual tone, like a 19th century circus announcer, framing Walker both as genius and spectacle. Walker’s own artist statement similarly stirred conversation before the exhibition even opened:

I don’t really feel the need to write a statement about a painting show. I know what you all expect from me and I have complied up to a point. But frankly I am tired, tired of standing up, being counted, tired of “having a voice” or worse “being a role model.” Tired, true, of being a featured member of my racial group and/or my gender niche. It’s too much, and I write this knowing full well that my right, my capacity to live in this Godforsaken country [...] is under threat by random groups of white (male) supremacist goons who flaunt a kind of patched together notion of race purity with flags and torches and impressive displays of perpetrator-as-victim sociopathy. I roll my eyes, fold my arms and wait. How many ways can a person say racism is the real bread and butter of our American mythology ... ?

Walker’s interest in audience responses dates back before her most well-known work, the 2014 “A Subtlety,” a 75-foot-long, 40-foot tall sphinx sculpture made from sugar and installed at the Domino Sugar Factory in NYC. That piece quickly became a viral phenomenon, too, with viewers flocking to take a selfie with the massive creature, sometimes pointing suggestively at her breasts, ass and labia. Some attendees were appalled by the flippant reaction to a piece addressing sugar’s relationship to the slave trade, industrialization and gentrification.

But Walker, who, it was later revealed, was filming every single audience interaction in the factory, predicted that viewers’ responses would play into her work. “I put a giant 10-foot vagina in the world and people respond to giant 10-foot vaginas in the way that they do,” she said during a 2014 talk at The Broad. “It’s not unexpected. Maybe I’m sick... [But] human behavior is so mucky and violent and messed-up and inappropriate. And I think my work draws on that.”

Since the 1990s, Walker appalled and mesmerized viewers with images that insult and traumatize; poke fun at people and turn them on; lie, recount facts and generally make a mess. Her work spares no one ― regardless of race or status, subject or viewer ― from being stuck in a big, timeless web. Whether you love the work, hate the work, buy the work, make the work, snap a selfie next to it or give it a glowing review, you’re in some way engaging with the dark stain of American history, and tainted because of it.

Today we see some of Walker’s gutting visual tactics ― the trickery, the abuse, the gaslighting, the “telling it like it is” ― mirrored in the leader of the free world. His American history, collapsed into cartoonish stereotypes, the “very fine people” and the “rapists,” “criminals,” and “sick people.” His political circus, a real life version of Walker’s America, a “freak show that is almost impossible to watch, let alone to understand.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Kara Walker’s “Sikkema Jenkins and Co. is Compelled to present The most Astounding and Important Painting show of the fall Art Show viewing season!” is on view at Sikkema Jenkins & Co in New York until October 14, 2017.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.