Democrats Are Terrified Of Losing Virginia's Big Election. They Should Be.

In Virginia’s gubernatorial race on Tuesday, the Democratic Party has a chance to score its first major political win since President Donald Trump’s election.

Many Democrats worry, however, that the party is going to blow what once seemed like a made-to-order opportunity.

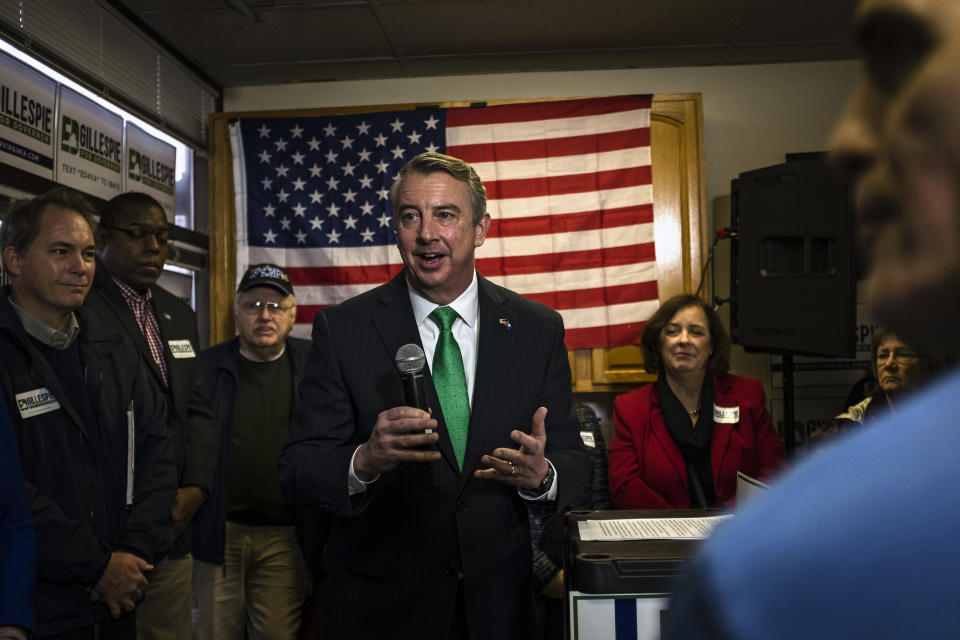

A victory for Democrat Ralph Northam, the current lieutenant governor, would provide the restive party a much-needed dose of optimism. But the consequences of a win by Republican Ed Gillespie, an inveterate Beltway power broker, would have reverberations far beyond Tuesday.

It would signal to Republicans, once wary of Trump’s toxicity, that wielding his brand of right-wing populism is a winning strategy ― even in a state with a popular Democratic governor that Hillary Clinton carried by a 5-percentage-point margin in the 2016 presidential election.

“It will be incredibly demoralizing,” said Yasmin Taeb, a Virginia Democratic National Committee member who has been volunteering for Northam’s campaign.

Taeb, who organized many of the Washington-based protests against Trump’s ban on travel from majority-Muslim countries, frets that a Northam loss could dull the enthusiasm of many of the people inspired to become politically active by the president’s election.

“If they feel as though they’ve been showing up since January, and it ends up not paying off on Nov. 7, I’m worried that we’ll see a lot of folks dropping off,” she said.

And that could hurt Democrats in other states in the 2018 midterm elections, in which the party hopes that anti-Trump fervor will propel it to gains.

If Northam loses, it will not be because of a lack of investment from state and national Democrats. His campaign had raised nearly $34 million as of the end of October, including some $7 million from the Democratic Governors Association. Gillespie, by contrast, had raised $24.5 million, of which some $10 million came from the Republican Governors Association.

The DNC also spent $1.5 million to help elect Northam and other Democratic candidates in the state. The Republican National Committee has spent $5 million to boost Republicans up and down the ballot.

The net result is a race where Northam and Gillespie are neck-and-neck. In RealClearPolitics’ average of major polls, Northam leads by 3.3 percentage points ― a sum within the margin of statistical error in most surveys.

Rather than suggesting a clear favorite in the race, the polling underscores a high level of uncertainty ahead of Tuesday’s results. Recent surveys have shown wildly disparate figures ― one poll showed a 17-point lead for the Democrat, another an 8-point advantage for his rival. Reasons for the disparity likely include differences in methodology and in estimates of who is likely to turn out.

Every statewide candidate officially runs independently in Virginia. But Northam is part of a de facto joint Democratic ticket with Justin Fairfax, running for lieutenant governor, and Attorney General Mark Herring, who is up for re-election. If elected, Fairfax, a 38-year-old attorney from the Washington suburb of Annandale, would be Virginia’s second black statewide elected official. (The first, Democrat Douglas Wilder, served as governor from 1990-1994.)

As a candidate, Northam, a 58-year-old pediatric neurologist, has emphasized his all-American biography and career. Born and raised on Virginia’s rural Eastern Shore, he graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and worked as an Army doctor during Operation Desert Storm before building a successful medical practice in the Hampton Roads region of southeast Virginia.

Northam has a long history as a moderate Democrat. He has admitted to voting for George W. Bush in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections ― votes he has said he regrets and attributes to his political inattentiveness at the time. As a state senator in 2009, Northam flirted with switching parties, and during his 2011 re-election bid, he described health care as a “privilege.”

Northam’s past stances and initial reluctance to make the race a referendum on Trump prompted a robust primary challenge from former Rep. Tom Perriello. Perriello’s backers included Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), as well as Our Revolution, the legacy organization from Sanders’ presidential campaign. Northam, who had the support of virtually every elected Democrat in Virginia, responded by revving up his anti-Trump rhetoric and tacking to the left on several economic issues. He ended up handily defeating Perriello in June.

In the general election, Northam has run on a relatively mainstream Democratic platform, including protecting women’s reproductive rights, using Affordable Care Act funds to expand Medicaid in the state, continuing to restore the voting rights of felons who have completed their sentences and increasing public education funding. He has touted the state’s strong economic performance under his and Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s leadership. And he has proposed providing free tuition for two years of community college or trade school in high-demand fields like information technology and health care, so long as the people who get their degrees commit to a year of public service of some kind.

Perhaps most of all, Northam has sought to appeal to widespread disdain for Trump in Virginia ― where, according to one recent poll, just 34 percent of residents approve of the job the president is doing.

But at times, Northam has appeared to be straining to appease all sides of the political spectrum. He puzzled observers with an ad promising that if Trump, the man Northam once called a “narcissistic maniac,” is “helping Virginia, I’ll work with him.” And last week, he said that as governor he would sign legisation banning “sanctuary cities” ― municipalities that limit their cooperation with federal immigration authorities. His comment dismayed progressives, and prompted one group to call his stance “gutless” and “racist.”

The flap shifted scarce media and activist attention to an internecine dispute in the final days before the election, and prompted hand-wringing about whether Northam was a strong candidate.

“If Northam loses, the progressive left says, ‘Perriello would have won because he would have run as a progressive populist and that’s what the base of Democratic Party is yearning for right now,’” said Quentin Kidd, a political science professor at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia.

Gillespie, 56, a former RNC chairman and longtime corporate lobbyist who grew up in New Jersey, personifies the kind of pro-business establishment Republican who is increasingly rare in national politics. As a GOP official and onetime White House aide to George W. Bush, Gillespie pushed the party to become more welcoming to people of color and backed comprehensive immigration reform that would provide a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

Right-wing populist and Trump campaign veteran Corey Stewart waged a nasty primary challenge against Gillespie fueled largely by promises to crack down on undocumented immigrants and safeguard Virginia’s Confederate monuments and heritage. Stewart even adopted a Trump-like epithet for Gillespie, deriding him as “Establishment Ed.” Gillespie ultimately prevailed, but by a shockingly close margin of just one percentage point.

Gillespie responded to the near-fatal populist challenge by doing his utmost to shore up the rural right-wing base that turned out for Stewart.

On the campaign trail, Gillespie has stuck to traditional, fiscally conservative Republican talking points. The heart of his platform is a proposal to cut Virginia income taxes by 10 percent across the board, one of several policies he argues will jump-start the state’s economic growth.

But on the airwaves, Gillespie has launched a scorched-earth campaign to paint Northam as an enabler of sexual predators and gangs of undocumented immigrants. In ads rife with racial overtones that began in September, Gillespie argued that policies embraced by his opponent have allowed the El Salvadoran gang MS-13 to run amok in Virginia.

Gillespie’s ads also have said that Northam, as governor, would try to strip Virginia of its Confederate history ― something the Republican stresses he won’t do.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

In final days of election, @EdWGillespie joins @realDonaldTrump in attacking athletes' right to free expression. Stand against hate. Vote. pic.twitter.com/gGFBdHhpyI

— Latino Victory (@latinovictoryus) November 3, 2017

Given Gillespie’s decision to pander to Virginia’s white-resentment-fueled right wing, a victory for him will again show Republicans that racial fear-mongering is a winning electoral strategy, said Kidd, the political science professor.

“Ironically, Republicans have criticized Democrats for two decades at least for running identity political campaigns, but Republicans ran what has by and large been an identity politics campaign with a little economic populism mixed in,” Kidd said. “If Gillespie wins it might mark another front in the culture wars in which Republicans embrace white identity politics.”

Indeed, other Republican candidates across the country are attacking Democrats by tying their policies to gang violence.

A Gillespie victory would almost certainly magnify that effect because it would occur in Virginia, “the place where [Trump] lost,” said Christian Dorsey, a Democrat on the Arlington County, Virginia, board of supervisors.

Of course, the most concrete impact of a Republican victory would be in the Old Dominion State itself, where McAuliffe has stood as a self-described “brick wall” between Virginians and the socially conservative policies of the Republican-controlled legislature ― particularly efforts to curb women’s reproductive rights. He has vetoed more bills than any governor in Virginia’s history, stymieing legislation that would have defunded Planned Parenthood, restricted voting rights and expanded access to handguns.

For Virginia Democrats, their neighboring state of North Carolina, where a Republican governor passed an infamous “bathroom bill” barring transgender residents from using the public restrooms of their choice, offers a frightening look at what life under unified GOP control could look like. (Following the election of a Democratic governor last year, the state repealed the law.)

“I look at North Carolina and everything that’s happened there and I say, ‘There but by the grace of God goes Virginia,’” said Atima Omara, president of the Young Democrats of America and a DNC member.

In addition, a Democratic loss at the top of the ticket would likely extinguish all hope of making major gains in the Virginia House of Delegates (no state Senate seats are on the ballot). Democrats, who recruited their largest number of House candidates in recent memory, are running in 17 GOP-held districts where Clinton won in 2016. Winning all 17 seats, though unlikely, would hand them control of the legislative chamber.

Even a narrower victory for Northam than had been hoped for could limit the Democratic pickups, said Taeb, the Northam volunteer.

If Democrats can pick up “6 to 8 seats, I would count it as a success,” she said.

But the implications of a Gillespie win extend well beyond the single four-year term to which he would be limited. During his last year in office in 2021, after the 2020 census, Gillespie would have the power to sign legislation redrawing Virginia’s congressional and state legislative districts for another decade.

And partisan gerrymandering is a Gillespie specialty. He helped oversee the GOP’s nationwide push to win control of state legislatures for the express purpose of redrawing political boundaries after the 2010 census to benefit the party. The severely gerrymandered districts that came out of that effort have handed Republicans nearly an unshakable hold on the U.S. House of Representatives and resulted in a net gain of hundreds of state legislative seats.

A Democratic governor could, by contrast, veto a Virginia redistricting plan offered by the Republicans and use the “bully pulpit” to inveigh against efforts to unduly favor the GOP, Dorsey said.

Omara of the Young Democrats of America remains “optimistic” that Virginia’s increasingly diverse demographics, disapproval of Trump and significantly stronger turnout in the primary bode well for Northam. But some people forget that Virginia is still a swing state that elected a Republican governor as recently as 2009, she added.

“We are a good reflection of what the country looks like,” Omara said. “We are a purple state. We have to fight for every vote.”

Ariel Edwards-Levy contributed reporting.

Also on HuffPost

Alabama State Capitol (Montgomery, Ala.)

Alaska State Capitol (Juneau, Alaska)

Arizona State Capitol (Phoenix)

Arkansas State Capitol (Little Rock, Ark.)

California State Capitol (Sacramento, Calif.)

Colorado State Capitol (Denver)

Connecticut State Capitol (Hartford, Conn.)

Delaware State Capitol (Dover, Del.)

Florida State Capitol (Tallahassee, Fla.)

Georgia State Capitol (Atlanta)

Hawaii State Capitol (Honolulu)

Idaho State Capitol (Boise, Idaho)

Illinois State Capitol (Springfield, Ill.)

Indiana State Capitol (Indianapolis)

Iowa State Capitol (Des Moines, Iowa)

Kansas State Capitol (Topeka, Kan.)

Kentucky State Capitol (Frankfort, Ky.)

Louisiana State Capitol (Baton Rouge, La.)

Maine State Capitol (Augusta, Me.)

Maryland State House (Annapolis, Md.)

Massachusetts State House (Boston)

Michigan State Capitol (Lansing, Mich.)

Minnesota State Capitol (St. Paul, Minn.)

Mississippi State Capitol (Jackson, Miss.)

Missouri State Capitol (Jefferson City, Mo.)

Montana State Capitol (Helena, Mont.)

Nebraska State Capitol (Lincoln, Neb.)

Nevada State Capitol (Carson City, Nev.)

New Hampshire State House (Concord, N.H.)

New Jersey State House (Trenton, N.J.)

New Mexico State Capitol (Santa Fe, N.M.)

New York State Capitol (Albany, N.Y.)

North Carolina State Capitol (Raleigh, N.C.)

North Dakota State Capitol (Bismarck, N.D.)

Ohio Statehouse (Columbus, Ohio)

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.