Density Isn’t Destiny in the Fight Against Covid-19

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As a Manhattan resident, I’ll be the first to admit that New York City in general and Manhattan in particular are not optimally designed for social distancing. People here tend to get around not in their own automobiles but on foot or by bus, subway, taxi or ride-share. We buy our groceries mostly not in giant wide-aisled supermarkets but in cramped little stores. We live cheek-by-jowl in apartment buildings, with elevators usually too small to accommodate the 6-foot rule. Most of us don’t have our own outdoor spaces, meaning that walking the dog or just getting some fresh air requires venturing out in public. And surely Manhattan is the only place in the U.S. where having your own washing machine is such a luxury that even lots of people in the top 10% of income distribution don’t (not because they can’t afford it but because their buildings ban them for fear of overtaxing ancient plumbing).

I am skeptical of the argument, though, that density equals danger in this age of Covid-19. For one thing, a bunch of East Asian cities even more densely populated than New York have successfully withstood the initial onslaught of the disease, indicating that well-conceived and well-executed public-health measures can more than counteract the disadvantages posed by millions of people living on top of one another. For another, New York City’s density is so anomalous in the U.S. context that I doubt its trials tell us much of anything about which other areas of the country are best equipped to fight off a pandemic.

What inspired this thought was actually not one of the many essays published lately heralding what anti-urban urbanist Joel Kotkin called a “coming age of dispersion” accelerated by the coronavirus. No, what got me wondering what kind of density does matter in a pandemic was a throwaway line in an otherwise perfectly fine Washington Post article about the apparent success of social distancing efforts in slowing the spread of Covid-19 in the states of California and Washington:

Some lessons of social distancing from West Coast cities also could be geographically and economically unique. They’ve got a fraction of the population density of many East Coast areas.

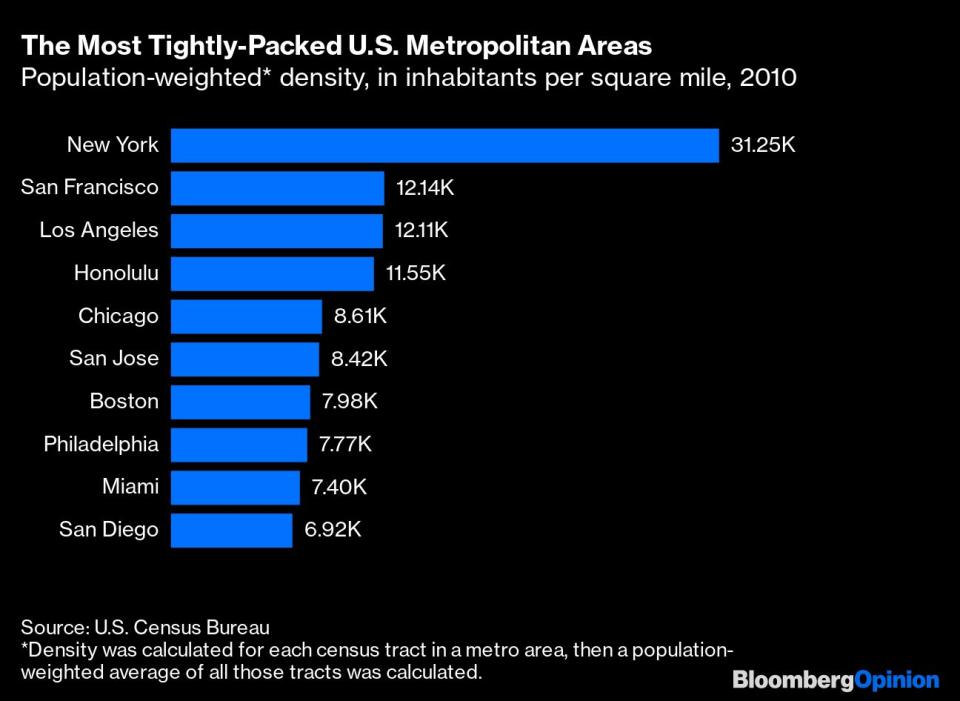

Really? The San Francisco and Los Angeles metropolitan areas are the most densely populated in the nation after metro New York. If you just divide population by land area, metro Los Angeles, which consists of Los Angeles and Orange counties, was only 7% less densely packed as of the 2010 Census than metro New York, which consists of too many counties in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania(1) to list here, some of which are pretty empty. In order to give a better sense of the density actually experienced by the average resident of a metropolitan area, the Census Bureau in 2012 published estimates that took the density of each census tract in a metro area, then averaged those densities weighted by the population of each tract. By that more sophisticated standard, metro New York was two-and-a-half times denser than metro San Francisco and Los Angeles, but those two were still significantly denser than other East Coast metros such as Boston, Philadelphia and Washington (and both the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas have surely become even more densely populated since 2010, as most new development there has consisted of apartment buildings going up near downtowns and suburban commercial districts).

The explanation for this perhaps surprising finding is that while the major cities of the West Coast aren’t necessarily denser than their East Coast counterparts, their suburbs are. The metropolises of coastal California in particular are squeezed between mountains on one side and water on the other, meaning suburban land has always been at a premium. The San Francisco metro area has the country’s smallest median lot size for single-family homes, at 0.13 acres, according to demographer Wendell Cox. Birmingham, Alabama, and Nashville, Tennessee, have the biggest, at 0.75 acres. In general, it is the metropolitan areas of the South that have the lowest population densities.

Does this make them safer in a pandemic? Well, it does give more room for the dog to run around, but beyond that it seems like there are diminishing returns to so much land. Once you’ve got some private outdoor space, a building entrance you don’t have to share with others and your very own laundry room (just imagine!), added space doesn’t really gain you much protection from infectious disease unless you’re capable of growing all the food and toilet paper you need on site. Closer-together houses also make it easier to check up on neighbors who might need help, plus the high cost of maintaining basic infrastructure for sprawling suburbs can cut into local government budgets for emergency services, public health efforts and the like.

Another way of measuring the sort of density that may be relevant to the spread of infectious disease is to see how dependent an area is on public transportation. I’m a big believer in New York City’s subway and buses, but cramming into a metal tube with lots of other people is undeniably problematic in a pandemic.

Again, the New York area is in a league of its own, accounting for 39% of the country’s public transportation commuters in 2018. Still, there’s San Francisco in second place again, well ahead of East Coast metros Washington and Boston. West Coast metros Seattle and Portland also rank pretty high. Los Angeles doesn’t quite make the top 10 (which is why I made the chart go to 11) but still beats the national average of 4.9%.

One possibly significant twist is that in the adjoining San Francisco and San Jose metropolitan areas, known collectively as the Bay Area, those who commute by public transportation have markedly higher median earnings than those who drive themselves to work. This is true to a lesser extent in metropolitan Chicago, Washington and Seattle, but not in any other large U.S. metropolitan area. This implies a bigger overlap in these places between those who customarily use transit and those who have been able to work from home during the pandemic — and possibly less reliance on transit by the lower-paid essential workers in health care, food provision and the like who in New York City are having to pack infrequent subway trains to get to their jobs. The Bay Area’s oft-lamented failure to build enough affordable housing near its train stations may be generating at least one not entirely terrible side effect.

In search of more pandemic-relevant density metrics, I came up with the percentage of housing units in structures of 10 units or more — on the assumption, based on personal experience, that it is hard to avoid running into one’s neighbors in such a building.

For once New York isn’t in first place, and again the metropolitan areas of the West Coast are quite well-represented — along with a couple of inland metro areas (Denver and Austin) that those fleeing coastal California’s crowding and expensive real estate have been known to flock to.

Finally, I looked at density within dwellings. If you’ve got more people in your house or apartment than you have rooms, it’s going to be a lot harder to isolate anybody with Covid-19. As it turns out, there are places in this country where a significant minority of dwellings are that crowded. Although the last two charts included only large metro areas (defined somewhat unscientifically as those with 500,000 or more workers for the first chart and 500,000 or more housing units for the second), I included all 392 metropolitan areas for the screen here because the ones with the biggest overcrowding problems tend to be on the small side.

Los Angeles really stands out here; among the other 49 largest metro areas in the country only San Jose (8.1%) and Riverside-San Bernardino (7.9%) top 7%. Beyond that, the list includes three Texas border communities, a couple of metro areas in expensive Hawaii and … a whole lot of California farming regions. Almost all the state’s San Joaquin Valley agricultural heartland is covered here (Visalia, Merced, Fresno, Bakersfield, Madera, Hanford), as are coastal berry and vegetable-growing regions (Salinas, Santa Maria) and the irrigated desert that is Imperial County (El Centro). My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Francis Wilkinson wrote last week that a major coronavirus outbreak among agricultural workers could be catastrophic. This is one key reason.

Still, that catastrophe seems to have been averted so far in California, which despite having a slew of metropolitan areas that score higher on a full panoply of density-related risks than pretty much anyplace in the U.S. but metropolitan New York, seems to be battling Covid-19 with significantly more success than, say, Louisiana or Michigan are. Density is not destiny in a pandemic.

(1) But not Connecticut, where Fairfield County makes up the separate Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk metropolitan statistical area, although it is part of the New York combined statistical area.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.