Biden’s Plan to Hit China With More Tariffs Is Mostly Symbolic

(Bloomberg) -- President Joe Biden is set to tariff sectors at the heart of China’s economic recovery, in a seemingly bold swipe at his nation’s biggest rival. In reality, the curbs will barely dent Beijing’s growth.

Most Read from Bloomberg

The US leader’s decision to hit China’s “new three” green goods could come as soon as next week, according to people familiar with the matter, as part of a review of existing tariffs. It’s the latest sign trade tensions are ramping up between the two superpowers in an election year where both candidates are being tough on Beijing.

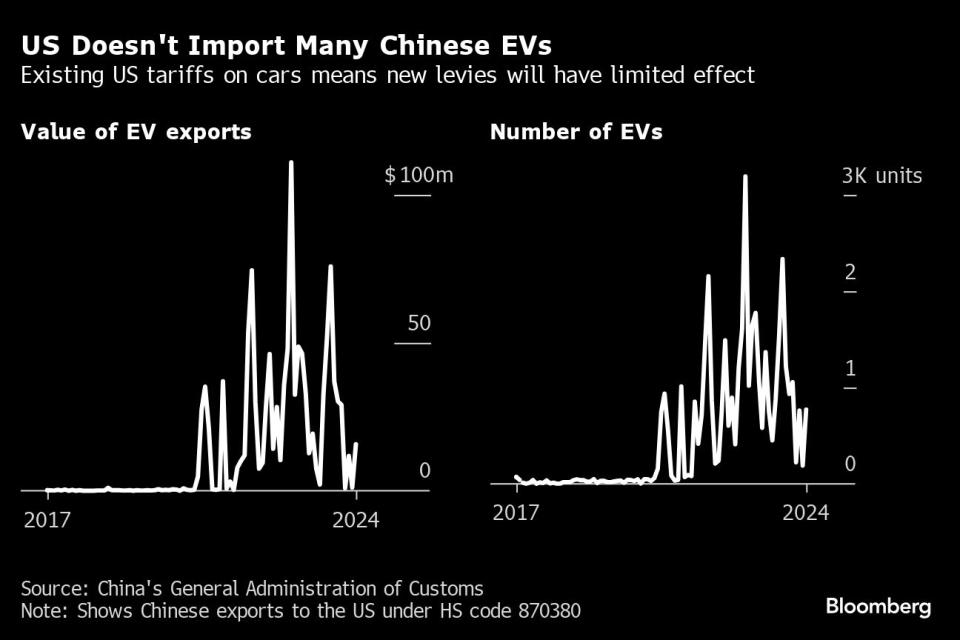

But while China’s electric vehicle, solar power and battery sectors are central to Beijing’s blueprint to manufacture its way out of a housing slump, they’re not reliant on US consumers. Existing tariffs locked Chinese autos out of the US market years ago, while solar firms mostly export to the US from overseas, avoiding similar curbs.

“I don’t think it will have a major impact, as the original tariffs already hit them hard,” said Henry Gao, a law professor at Singapore Management University, who researches Chinese trade policy. “The Chinese government will issue statements protesting the new tariffs as usual, but probably will not announce new countermeasures for fear of backlashes during an election year.”

While Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian vowed Beijing would “take all necessary measures to defend its rights and interests” at a regular briefing in Beijing on Friday, so far his nation’s response to other similarly symbolic gestures has been muted.

Biden is trying to balance looking strong on China to protect US jobs without unleashing economic pain that could destabilize the relationship: Last month, he vowed 25% tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum that were largely toothless, as the Asian nation sells little of either metal to America, and a shipbuilding probe that will likely take a long time to conclude.

If China was to retaliate, it could target US agricultural exports by trying to increase imports of products such as soybeans, or corn from other countries like Brazil, or pork from Canada or Denmark. Over the past 18 months, Chinese imports of Brazilian corn has gone from nothing to about $700 million a month, taking market share from the US, which used to be the largest source.

Perhaps, the real danger for Beijing is that Biden’s symbolic swing at EVs sets a precedent for countries where China does have market share, said Dylan Loh, assistant professor of politics at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“It may well be the harbinger of other moves by the EU because obviously they are also looking very seriously at that,” he added, referring to the European Union, which last year opened a probe into China’s state subsidies for its world-beating EV market.

Biden has so far been reluctant to use blanket tariff increases against China as former President Donald Trump did, preferring more targeted strikes against high-tech companies in the semiconductor and other strategic sectors. Those tools have failed to prevent Chinese firms from succeeding in becoming dominant in green technology, where they’ve had a first-mover advantage.

Any US decision to impose new tariffs on Chinese exports would bring into focus a little noticed effect of tensions: Direct trade between the two largest economies shrank over the past five years.

In 2023, only about 15% of Chinese exports went directly to the US, the lowest amount since China joined the World Trade Organization more than 20 years ago. Only about 7% of US goods exports went to China last year, down from almost 10% during the pandemic.

Much of that trade now goes via other countries, making the output of Beijing’s companies harder for the US government to tariff — especially if they are exporting Chinese components to be combined into finished products in Vietnam or Thailand.

If the US does try to block them it risks souring ties with nations it wants to bring closer. That shift shows how global supply chains have reorientated themselves to deal with the effects of the tariffs put in place during Trump’s administration.

Solar panels perhaps best symbolize the difficulty facing the US. Due to existing tariffs, there’s little direct export of such products from China to the US, with much of that trade now going via southeast Asia. An investigation last year found that some manufacturers were illegally bypassing US tariffs on Chinese solar equipment by shipping via nearby nations. No action has been taken so far to block that, despite the pleas of manufacturers in the US.

The curbs the US is considering on EVs won’t make much of a difference. Chinese cars are already subject to a 27.5% tariff and in February the White House announced a new probe into “connected vehicles” from “countries of concern, including the People Republic of China.”

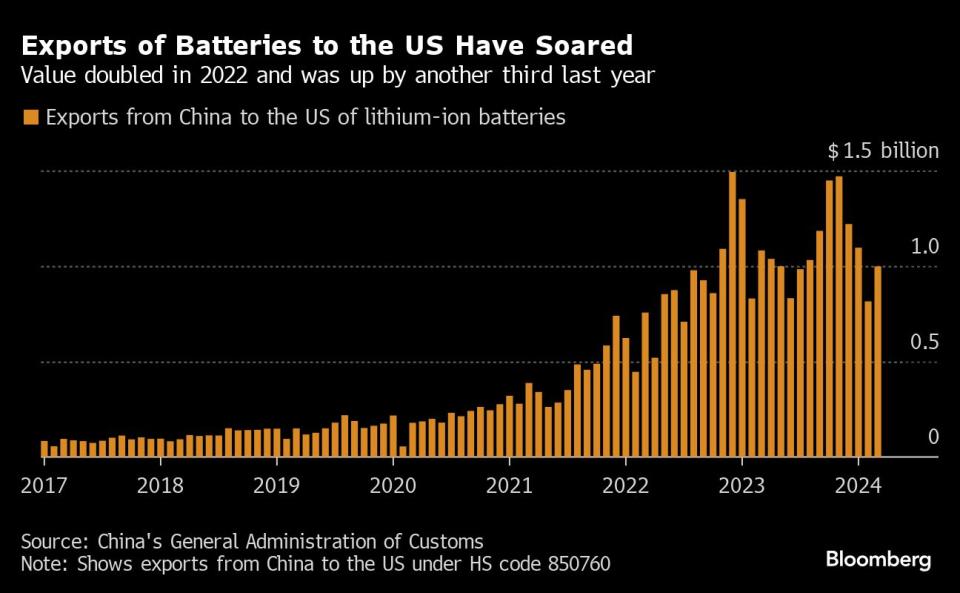

The sale of Chinese batteries to carmakers could have an impact. Those exports have risen rapidly in the past few years as Chinese companies steamed ahead as market leaders, and US firms struggled to meet the demand for electric vehicle batteries.

However, the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act are designed to exclude batteries from China, meaning such trade would likely have tapered off anyway.

“We’ve long been expecting more anti-China rhetoric and policies to be amplified closer to the election,” said Chen Shi, fund manager at Shanghai Jade Stone Investment Management Co., noting that the effects of such policies were shrinking.

“China has proven though the years that its core edge lies in a strong and comprehensive industrial structure,” Chen added, “and that cannot be challenged with tariffs.”

--With assistance from April Ma and Josh Xiao.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.