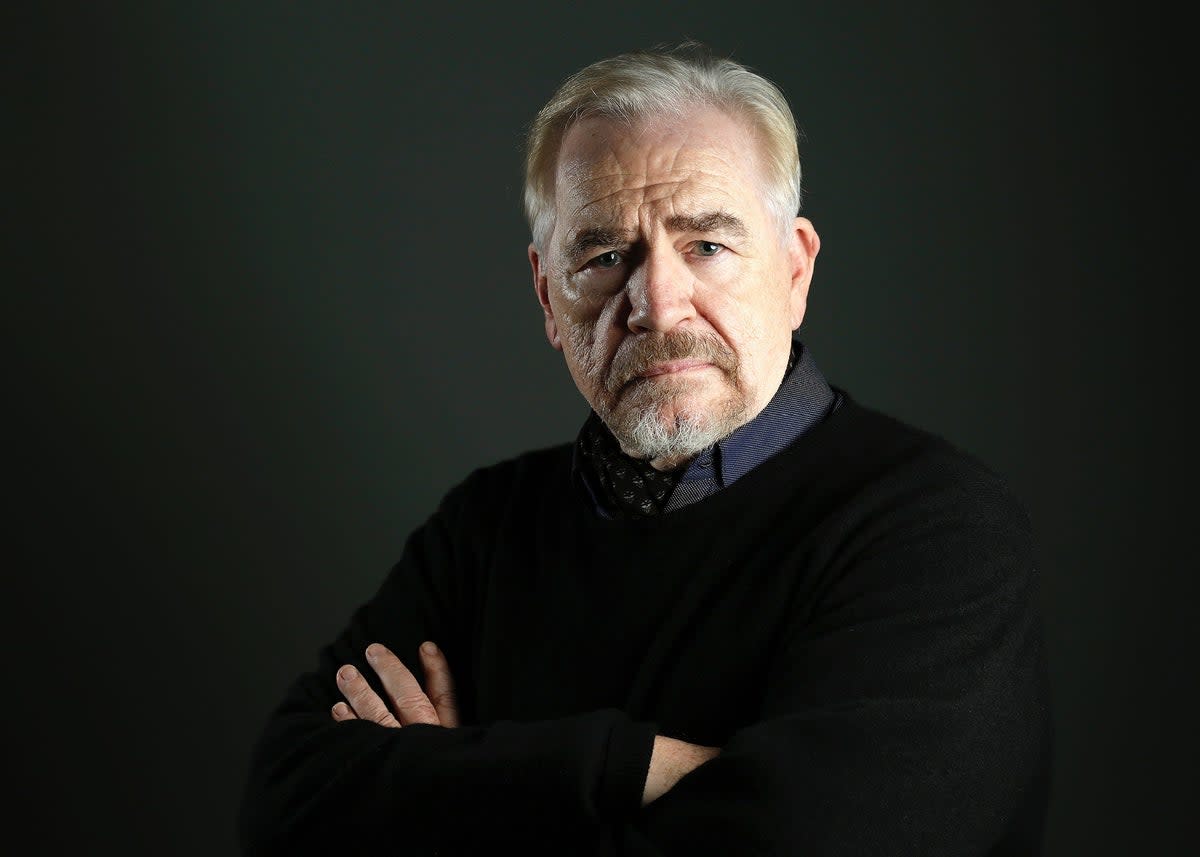

Brian Cox: ‘I can’t afford $110 each for one night at the theatre’

If Brian Cox has completed an interview without using the f-word, I’ve yet to read it. Like Logan Roy, the Succession character with whom he’s now synonymous, Cox uses swearing like an ever-reliable crutch. He’s been rehearsing Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical masterpiece, Long Day’s Journey into Night, and when we meet, in a spare room above a central-London theatre, the topics on the 77-year-old’s mind are family feuds, addiction, and what it means to be a “Mick”. After six decades as a celebrated stage, TV and film actor, Cox is doing the opposite of slowing down. “Now that I’m older,” he declares, “I don’t have time to f*** around!”

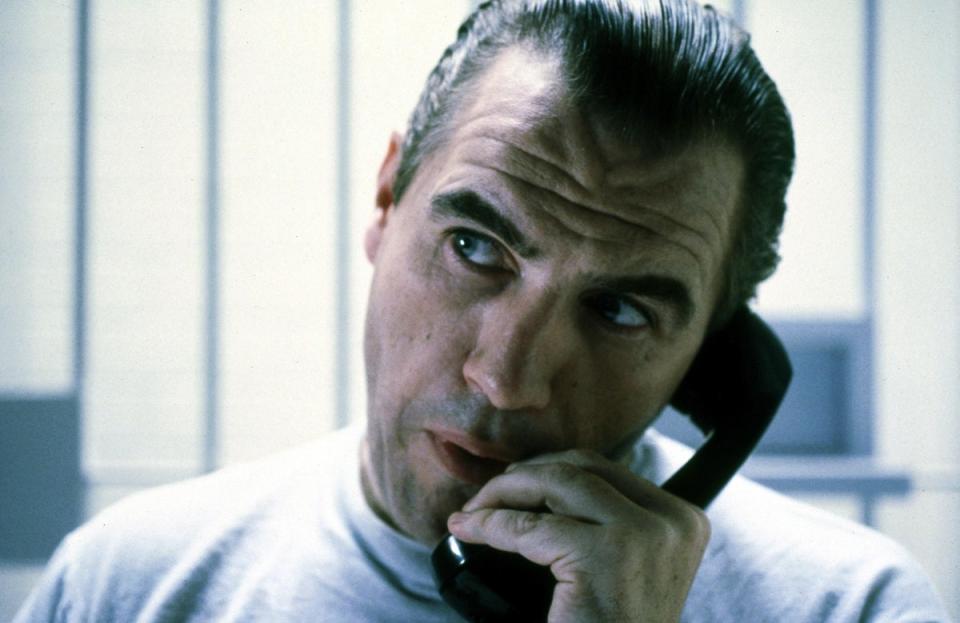

For years, he was everyone’s favourite chameleon: convincingly coiled and obstreperous in Manhunter, wryly avuncular in Rushmore and Adaptation, dependably sneaky in two instalments of the Bourne series. As an odd-job man, he delivered in spades. Then came the game-changer.

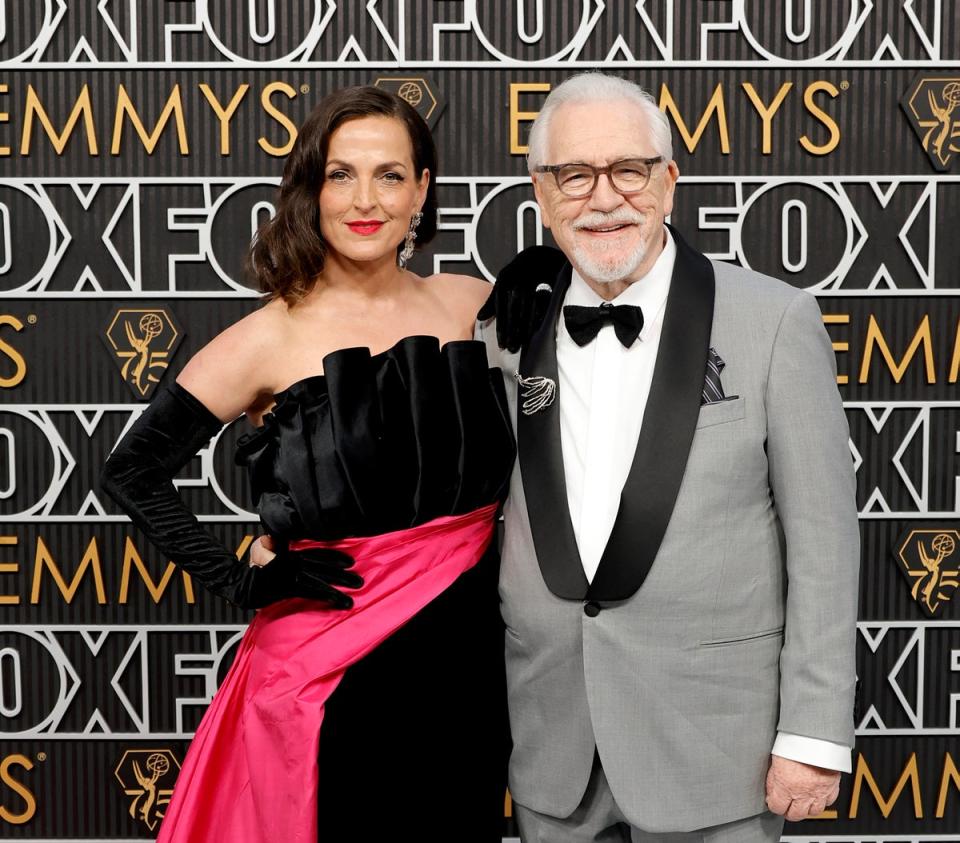

Cox always had the capacity to be shirty, but since he appeared as the CEO of Waystar Royco, his temper has become a talking point. His co-stars on Succession have variously described him as “frightening”, “scary”, “terrifying” and capable of flying into a “diabetic rage” (Cox is, to be fair, diabetic). Meanwhile, fans are hooked on his angry-old-man act. Especially female fans, according to Cox’s wife, the actor Nicole Ansari (“Women are flocking”).

Chutzpah comes with the territory. Last November, Cox sauntered onto Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night US talk show in a pair of faux leather trousers that were unbecomingly snug (when he sat down, the internet cringed). Undaunted, Cox skipped onto ITV’s Loose Women and heaped praise on his personal stylist. Yet there’s more to Cox than showbiz hoo-ha. A few months ago, I saw him in north London at The Moonwalkers, a show about the Apollo missions. Hands clasped behind his back, Cox was standing by himself, neither seeking nor hogging the limelight. Lost in thought, he was just a face in the crowd.

Today, with a crumpled tissue stuffed into the pocket of his baggy jogging pants, he looks even less starry. He’s spent the morning with co-stars Patricia Clarkson, Laurie Kynaston and Daryl McCormack. Having sunk into a chair, he notes that the room is draughty, and asks, politely, if I can shut the door. Cox starts munching on a pallid ham and cheese baguette, occasionally swigging from a bottle of cola. He’s not doing this for the perks.

O’Neill’s play is the perfect vehicle for an actor determined to avoid complacency. Cox’s character, James Tyrone, is an Irish-American thesp who was poor as a child and has made a fortune by giving the public what they want. Now – along with Mary, his resentful, traumatised “dope fiend” of a wife, and Jamie and Edmund, his two boozy sons – he’s rueing his choices. Because money can’t fix what ails his emotionally haunted clan.

“I have a little bit of the O’Neill in me,” admits Cox. He has “no idea” if the production will be a hit. “It’s a beast of a play,” he says with gloomy relish. “It’s unremitting, never lets you off the hook... written by a very depressed individual, who was haunted from when he was a little boy by what he saw. It’s a play I’ve always wanted to do, and I’m now bitterly regretting doing it because it’s f***ing hard!”

Cox believes the background of Long Day’s Journey into Night is the sense of displacement caused by Irish migration. “The way this family behaves completely comes out of the great hunger. Both the father and the mother are a product of that blight, which seized Ireland and was used as an excuse to commit sub-genocide.”

For Cox (who describes himself as “88 per cent Irish and 12 cent Scottish, which means I’m 100 per cent Celt!”), this stuff is personal. “The famine forced everybody to leave. My people went to Scotland, lots of people went to America.” And in America, says Cox, the class system put “Yanks, who were Protestants” on top. “The Irish were like the slaves!” he continues passionately. “They came in, they did everything. They were sneered at... being a ‘Mick’, it’s not got a very good rap! No wonder we have this feeling that we’re second-class citizens!”

He may sound gun-blazingly pro-Irish, but some of Cox’s comments are a tad sweeping. In fact, Irish readers may find themselves thinking, “With friends like Brian...”

Cox complains that in Irish Gaelic, “There’s no word for ‘no’. Being endlessly equivocal has its charms, but it’s not necessarily helpful to the general body of the people. What I love about Scotland is that they’ve learnt to say the word ‘No’!” Later, discussing his maternal grandfather, whose parents came from Derry and Donegal, Cox says: “He was an alcoholic, which, of course, is the Irish thing. That’s the f***ing thing. They always go to the booze!”

They certainly do in O’Neill’s play, which Cox admits is almost “too” close to home – not because his parents drank, but because they were often at loggerheads. Cox’s socialist dad, Charles, ran a grocer’s shop in Dundee and, much to the annoyance of Cox’s mother, Mary/Molly, was famous for being a soft touch. “My father was determined to be the generous soul. My mum said, ‘Just remember, Brian, charity begins at home.’”

When Cox was eight years old, his father, age 51, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. “My poor ma! She felt she’d badgered my father too much. She felt very responsible for getting on his case.” Three weeks later, Charles was bedbound and close to death. “My mother was there, fussing,” says Cox, grimly, “and my father was looking at her. My brother-in-law was in the room and he told me, ‘I’ve never seen such a look of dislike on one person’s face, for another person.’”

Cox is sitting forward: it’s like he’s seen a ghost. “But I think there’s another interpretation!” he yelps, miserably. “I think my father was looking at my mother with a huge sense of loss. They hadn’t made what they were trying to make together. He felt he’d failed. We’ve all felt that in relationships.” He gulps. “It’s a terrible thing to happen.”

Once debts were paid off, the Cox clan found themselves on the breadline. It was too much for Mary, who attempted suicide (she was eventually institutionalised and given electroconvulsive therapy). Cox, one of five, was looked after by his three older sisters, themselves struggling to put food on the table.

In Long Day’s Journey Into Night, the outrageously penny-pinching James Tyrone delivers a wrenching speech about the horror of watching his single mother struggle to feed her children. Cox nods. “The poverty stuff [in the play] always seems a bit of a joke. But it’s not. I’ve experienced it. It’s not a joke.” When Mary eventually came home, was she her old self? “No, she never got back to being herself,” replies Cox, softly. “She never reclaimed her self. After the breakdown she could be funny, but she was always eccentric. She became so tiny. Shrunken.”

The poverty stuff in the play always seems a bit of a joke. But it’s not. I’ve experienced it. It’s not a joke

As you’d expect, scars from this period remain. Cox wants to be generous like his father, but he associates financial benevolence with disaster. Cox thumps the table. “I’ve always been caught between the two things.” Which means he can’t relax: “Everything is ephemeral!” he declares, eyes blazing. “It could all go away from me in a second!”

Cox had two children with the actor Caroline Burt, both of whom went to public schools (“Alan went to St Paul’s, Margaret went to Cheltenham Ladies’ College”). Cox married Ansari in 2002, and the couple, along with their two sons, Orson and Torin, have a home in downtown Brooklyn, as well as places in upstate New York and Primrose Hill. Cox’s fortune is estimated to be worth over $15m (£11.9m). Sounds cushy, right?

Not according to Cox. “I would never use the word ‘comfortable’ about myself. I don’t feel comfortable. I never look at my accounts. That’s just a nightmare to me.” He performs a mime of himself shielding his eyes and rearing back from scary bits of paper. “I can’t look through my accounts and say [he puts on a chirpy voice], ‘So what have I got here? Hmm... So that’s getting along nicely!’” He just wants to know if there’s something in the bank. Again, he provides an internal monologue, this time in a stricken voice. “‘I’ve got enough money? Fine. Fine. Let’s leave it at that.’”

Still, he frets about being profligate. And his kids, according to him, don’t get it. “I’ve got sons. I go, ‘No, I can’t afford to pay $110 each (about £90) for one night at the theatre. For all of us! For five of us!” (I’m guessing he’s including his eldest son in this.) He looks at me, half pleading, half defiant. “I do. I have resentments about that!” He does another little pantomime of himself, this time fighting off his demanding kids. “Urgh!” he says.

What’s disarming is that, even as he wallows in this ocean of self-pity, he’s also wise to himself. “I go, ‘Wait a second, this sounds familiar. This is very familiar. It’s to do with displacement. My sense of displacement!’”

Do his children tease him? Do they say, ‘Just remember, Brian, charity begins at home’? His offspring are scathing, Cox says, “all the time”. He laughs, properly amused. “I can’t pick out the worst thing they’ve said about me because there have been so many.” Then he frowns. “I don’t think it’s easy having an actor as a father. In a way, you seem amiable and very there, but you’re not.”

He’s not especially happy that Alan chose acting as a career. Or that both Orson and Torin want to go “into the business, in some way or other”. Then again, he thinks the worst scenario is to love an actor yet not have a connection to acting. “That’s the thing about the theatre. It’s a great place, but only for people who work in it. Otherwise, you can feel alien. That why I – in terms of the opposite sex – have always been involved with actresses. It’s not because of the obvious thing – that it’s easy, because you meet them and are working with them. It’s because they understand the displacement. They have a deeper understanding that anything we create together is created on a very tectonic foundation.”

Those wondering if Cox has been put on some kind of starvation diet will be relieved to hear he now opens a bag of crisps. Jauntily popping said crisps into his mouth, he touches on various national debates. “Stupidly, we [the Scots] gave England the Stuart tradition. They didn’t want it, and got a bunch of Germans to run the place!” With regard to UK-bound refugees: “Why the f*** do all these people want to get on a boat to come to England, of all f***ing places?”

Yet he keeps circling back to family life. In his gritty 2022 memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, Cox shared that his daughter, Margaret, developed anorexia as an adult and almost died. “I know what addiction is about!” says Cox, thumping the table again. “I’ve lived with people who’ve been addicted! Only they can do it. Nobody else can do it on their behalf. Only they can... [he pulls an agonised expression] shift that. Example: anorexia is a control thing. You can be the mother or father of an anorexic and there’s nothing you can do about them. They have to do it. They have to make that decision – to say, ‘I’m not going to go down that road.’”

Cox has twisted round in his chair, and hoisted up his right leg so it’s resting on the chair next to him. Presumably his leg is aching, though he’s not complaining. Long Day’s Journey into Night lasts for three hours. Is he a masochist?

He’s appalled. “No! Why would you say that?” Well, last year, when he was doing The Score, a play about JS Bach, in Bath, he talked about how exhausted he was, yet here he is, doing something even more knackering. And next up, he’s planning to make his directing debut with a film set in Scotland called Glenrothan. “Yes, I suppose that is a form of masochism,” concedes Cox. “I can understand why you think that. But I never really want to inflict things on myself, except work. I’ve one life, and I’m coming to the end of it. So I’m trying to be more and more precise about what I do. Less general. Which means the demands are greater. You work with people who want to take shortcuts and you go, ‘No!’”

Honestly, it sounds like he’s addicted to his job. He looks at me. “You do your job. Why do you do what you do? Think about it.” I do as instructed. “You see!” he says, after listening to my reply. “That’s your raison d’etre. Well, I’ve been f***ing at it since 1961, and I’ve done a lot of work where I’m just earning a living. But I’ve also worked with people who helped me set really high standards.”

There’s a knock on the door; the PR says we have five more minutes. “It’s OK,” Cox tells me. He gestures with his hand, as if to say “Take your time.”

Cox has always bigged up matriarchies, and does so again today. (“The history of women is such a shocking and appalling history... it’s just the pits, we’ve never acknowledged the need for a proper, decent matriarchy.”) He’s also vocal about the astute and gifted women who’ve shaped his life.

He explains it was a 16-year-old Indian dresser who unlocked his potential as an actor. “I was in my mid-thirties,” says Cox. “I was in India, playing Macbeth, in a not particularly great production. The dresser was a Kathak dancer [Kathak is a classical Indian dance form]. She said, ‘I’m watching you work and I really feel you want to move!’ I was like, ‘You’re not wrong there, girl! I just sometimes don’t know how to move, or how to motivate myself to move.’” The dresser told Cox to trust his body, not his mind. With her encouragement, he went “further and further, particularly in the dagger scene. Eventually I was crawling all over the floor!”

After that, Cox went to the National, “which was OK, but never quite as releasing as I wanted”. It was when he did Titus Andronicus at the RSC, with Deborah Warner, that it all came together. “Because Deborah allowed that movement to be part of the experience.” He thinks it’s a shame he only got to work with “a major female director” in his forties. “In my early career, it was all men. Some brilliant men... but Deborah is so visceral. With her, it’s all about the effect, in a good sense.” His face is glowing. “I love Deborah. I didn’t work enough with her – I only did the one play – but it was the best time ever!”

He notes with pride that it was his idea to cast Patricia Clarkson as Mary, “which has to be the biggest female part ever. The demands it places on Patti! She’s doing an extraordinary job, but I can see how painful it is for her.” He’s seen several of Clarkson’s films, “all of which I would not be able to repeat the titles of. But I’ve always admired her. She’s from New Orleans. She hasn’t got that – ” he wrinkles his face – “Northern American sensibility. She’s a woman of the South. And that is something quite else!”

O’Neill’s play, says Cox, might seem like a corrective to the glossy Succession, but both projects are dealing with human value. “How do we appraise human value?” asks Cox, getting all stirred up. “O’Neill and Jesse [Armstrong] critique the values we’re surrounded by. They have a political sensibility that takes issue with entitlement!”

The PR is back, and says firmly that Cox is needed in the rehearsal room. Cox wants to know if I’ve got enough material for the article. “Is this OK? OK. Fine. Good.” I say I feel guilty he had to eat and talk. “Hah!” he says. “That’s not new, let me tell you!” And, clutching his bottle of cola, he walks stiffly to the door.

Anyone who spends time with Cox can see he’s a social justice warrior, a feminist, and physically pained by huge outlays of cash. Yet it’s recently come to light that he belongs to the men-only Garrick Club (annual rates: £1,600). When I first heard the news, I was stunned. Actually, though, it makes sense. Being “torn” is central to who Cox is. Should he attack the status quo or cosy up to it? He can’t decide, so does both.

In Long Day’s Journey into Night, James Tyrone is a self-made actor who’s charismatic, hot-tempered, and plagued by confusion as to where he belongs. Truly, it’s a part Brian Cox was born to play.

‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’ is at Wyndham’s Theatre from 19 March till 8 June

For anyone struggling with the issues raised in this article, eating disorder charity Beat’s helpline is available 365 days a year on 0808 801 0677. NCFED offers information, resources and counselling for those suffering from eating disorders, as well as their support networks. Visit eating-disorders.org.uk or call 0845 838 2040