Netflix’s Griselda: The true story behind the ‘cocaine godmother’ portrayed by Sofia Vergara

“No, my name is Betty,” she said in Spanish, looking up from her Bible in practised nonchalance.

The passport on her nightstand, under a headscarf and next to a .38 calibre revolver, said otherwise; her name was Lucrecia Adarmez. But that was as phoney as another favourite alias, Arichel Vince-Lopez.

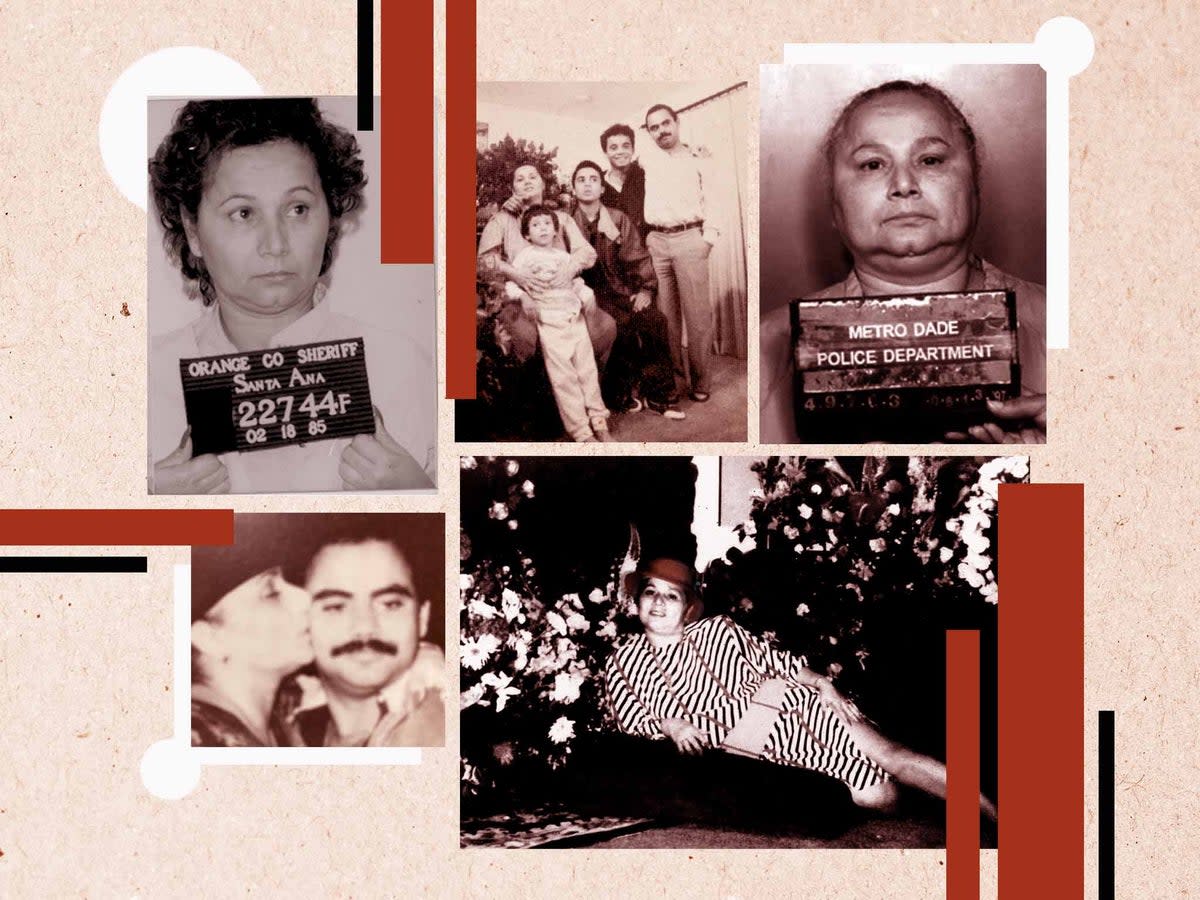

By the time Bob Palombo caught up with the “chameleon, who could change her appearance at will” after 11 years, she had been known by many names: La Dona Gris, La Gorda, La Gordita, The Black Widow, La Madrina.

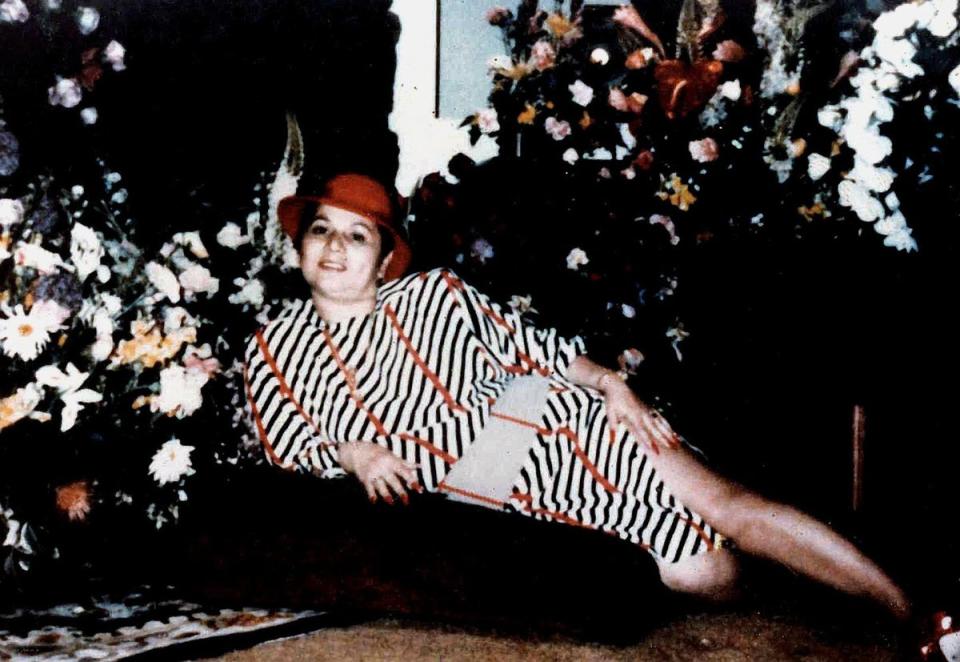

In that moment of reckoning, she regressed to Betty, given for a long since passed resemblance to Betty Boop, if the 1930s character had spent decades in a psychotic spiral of drug-fuelled orgies and homicidal paranoia.

The cleft chin and cartoonish dimples remained, and like so many before him, Palombo was mesmerised. He kissed her on the cheek and introduced himself as the Drug Enforcement Administration Special Agent who was to finally bring down The Cocaine Godmother: “Hola, Griselda. We finally meet.”

“She didn’t kiss me, I can only think what she would have liked to do,” Palombo, now retired, recalled to The Independent of her 1985 arrest.

Kill him, if he had to guess. And without remorse. Griselda Blanco killed lovers and enemies alike. Preferably with one of her Pistoleros hitmen, riding up on a motorbike, and shooting at point-blank in the preferred method that she popularised and how she, in a serving of street justice, was assassinated outside a Medellin butcher shop in 2012.

But for a short moment after being dragged out of a California townhouse in Irvine, Orange County, on 17 February – her birthday weekend – she showed a glimpse of the vulnerability beneath the bravado.

“She was pretty tough and standoffish, a typical Colombian move I would say, nonchalant, not really showing any real emotion, but when we put her in the car, I was in the backseat with her, and the other agent was driving. We drove up to Los Angeles, and when we got close to the courthouse is when she became visibly shaken,” Palombo remembered.

“I mean, visibly shaken, she was shaking, and she grabbed my arm and you could feel her shaking and she turned and she threw up on my shoulder. Not a lot, it was mostly just bile, but she knew the proverbial s*** had hit the fan. And it was time for her to meet her accusers.”

In the 37 years since, Blanco’s place among the history of Colombia’s drug lords has grown in prominence, elevating her infamy alongside Medellin Cartel contemporaries Pablo Escobar and Carlos Lehder.

As in life, Blanco has become a chameleon in death. Her image as a Queen among Kings has seen her portrayed in TV and film with increasing star power and box office draw.

The year she was killed, Blanco was played by Luces Velásquez in the Colombian telenovela, Escobar, el patrón del mal. Catherine Zeta-Jones took the role in a 2017 Lifetime movie, The Cocaine Godmother. Now, Sofia Vergara is starring in the Netflix series, Griselda, which is finally available to stream. And Jennifer Lopez will take the starring role in the Hollywood biopic, The Godmother, currently languishing in development.

Lifetime billed Blanco as a “pioneer”, Netflix calls her a “savvy and ambitious Colombian businesswoman”, and Lopez praises her as an “anti-hero”, though her three murdered husbands and the families of the dozens, maybe hundreds, killed at her whim may say otherwise.

“She is all things we look for in storytelling and dynamic characters – notorious, ambitious, conniving, chilling,” Lopez said when signing on for the role in 2019.

The reality of Blanco’s life and crimes is less airbrushed. Long before being popularised among English-speaking audiences in the 2006 documentary Cocaine Cowboys, and its 2008 sequel Hustlin’ with the Godmother, Blanco’s story was already one of legend in the annals of the US’s crime-fighting apparatus.

In 1993, the DEA published an internal magazine titled Drug Enforcement to mark the 20th anniversary of the agency’s creation, by former president Richard Nixon, to wage the neverending “war on drugs”.

The document chronicles key moments in the agency’s history, from its “family tree” dating beyond prohibition, to major drug trafficking routes, to the murder of special agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena (played by Michael Pena in Netflix’s Narcos: Mexico).

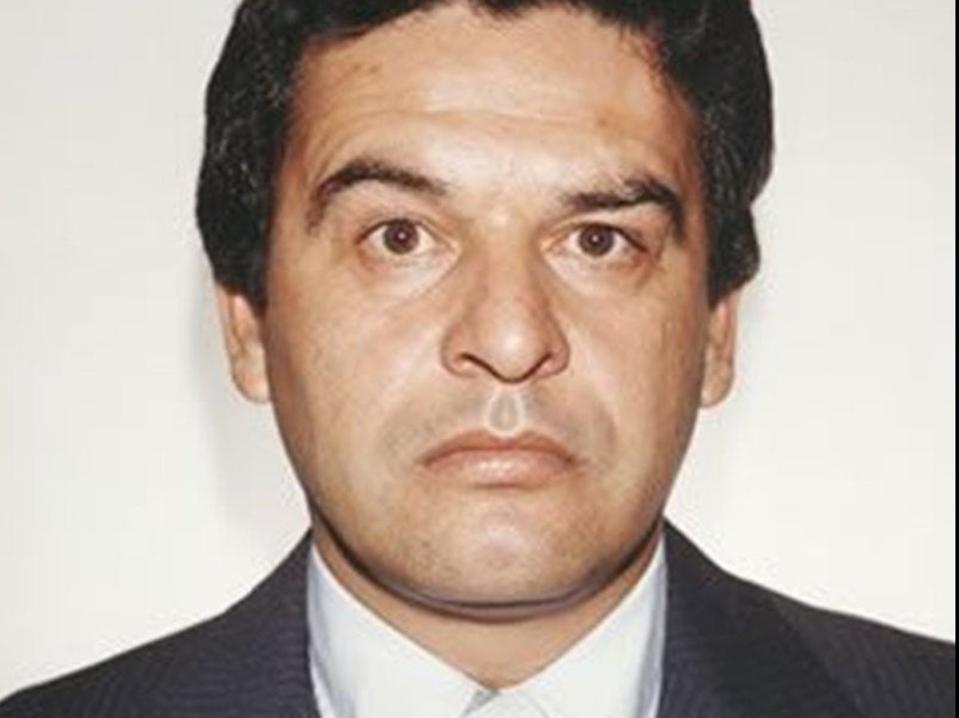

The chapter titled “Rogues” lists the top 5, well, rogues, of the DEA’s first 20-years. Blanco topped them all. She was considered an even bigger fish than the Medellin Cartel’s founder, Carlos Lehder. Escobar would not be killed until December of that year.

The DEA ranked Blanco’s capture above the biggest scalps of the United States’s home-grown underbelly: Leroy “Nicky” Barnes, leader of the largest drug ring in New York; Wayne “Akbar” Pray, the head of a New Jersey trafficking organisation with tentacles across the country, and chemist George Marquardt, responsible for 126 overdose deaths with a drug he manufactured to be up to 400 times more potent than pure heroin, the then little-known fentanyl.

What made Blanco so feared, and her capture so revered, among the men of her time? In the DEA’s own words from 1993: “Griselda loved killings. Bodies lined the streets of Miami as a result of her feuds. She gathered around her a group of henchmen known as the Pistoleros. Initiation into the group was earned by killing someone and cutting off a body part as proof of the deed. It is said that one of the Pistoleros assassinated a rival by riding up to him on a motorcycle and shooting him point-blank.”

It became the trademark of the Medellin cartel. And the unmissable exclamation mark of her assassination.

“She not only killed rivals and wayward lovers, but used murder as a means of cancelling debts she didn’t want to pay. A particularly bloody massacre that took place in July 1979 in a Miami shopping centre became known as the Dadeland Massacre.”

By the time bodies began piling up in Miami, Palombo had been circling Blanco for the better half of the 1970s. She eluded capture in Queens, New York, during 1974’s Operation Banshee, one of DEA’s first major operations since it formed a year earlier in 1973.

Twelve Colombians were convicted of smuggling more than 20 pounds of cocaine, worth $2.5m (or $15m in with inflation), a week, from 1972 to 1974, in cargo containers, speedboats, suitcases, clothing, hollow wooden coat-hangers, and even a dog cage containing a live dog, according to a 1976 report on the trial in The New York Times.

“But we never laid eyes on her,” Palombo said. “Her voice never really showed up on the wiretap investigation. Or on much of anything.”

Blanco had fled to Colombia, where the DEA tried to keep tabs and get her to flip on the Colombian cartels. “But that was wishful thinking and pie in the sky, because that never happened,” Palombo added.

She was tracked in Colombia until at least 1977, but ultimately disappeared into barrios and remained an enigma. There were rumours she was shot in Miami in 1977 and 1980, but Palombo wouldn’t get close again until almost 10 years after she was first indicted during Operation Banshee.

Meanwhile, much of what became known (at least outside of Colombia) of Blanco and her early life came second-hand from DEA informant Maria Gutierrez, Blanco’s travel agent who eventually became a friend, trusted confidant and unrequited love interest.

On February 15, 1943, while the world was at war with Nazi Germany, Griselda Blanco Restrepo was born in Cartagena on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. Abandoned by her father, Blanco was taken to Medellin at a young age and grew up in a shanty slum where her mother, said to be an alcoholic prostitute, beat her savagely.

Forced onto the streets, she met her first husband and mentor Carlos Trujillo, a heavy drinker and small-time document forger. The pair made their way to New York in the mid to late 1960s. Now in her 20s, Blanco went from pickpocketing, forging fake ID documents to “small amounts of marijuana” (as far as the DEA knew).

“Right off the bat, there she is,” Palombo said. “Her mother being an alleged prostitute … the thieving, her getting involved in phoney passports, pick-pocketing, her whole life was brought up around crime. There was no wholesomeness in her life. You almost, almost I say, and I don’t say this a lot, you almost have to feel sorry for somebody that never had a real chance.”

In 1960s New York, cocaine wasn’t particularly popular in the low-grade paste form called basuco, or “bazooka”. But as the drug was crystalised and demand increased late in the decade and into the 1970s, the “innovative businesswoman” backed off marijuana and purchased an undergarment business. She created secret compartments in bras and girdles and recruited couriers to import cocaine by the body load.

She used multiple sources for her supply and like her contemporary, Carlos Lehder, pushed for pooling resources and sharing risks with other drug traffickers, creating what became the Medellin Cartel and setting the stage for its most infamous leader, Pablo Escobar.

“My mum had been balling since the 60s,” says her youngest and last surviving son, Michael Corleone Blanco. “Pioneer s***. Never again, that s*** was crazy,” he added.

Named after Michael Corleone from gangster film The Godfather, Corleone Blanco filled in the gaps of his mother’s history during a 2019 podcast, Berner’s Round Table.

She got her start by bringing 100 mules and workers up into the Andes mountain ranges and bringing the famous Colombian Gold strain of marijuana to Medellin and, by extension, the world.

“And that was the only neighbourhood that had killers, Afro-Colombians, whores, bootlegging and marijuana, and there was a lady that controlled that. And her name was Griselda Blanco,” he said.

After relocating from New York back to Colombia in the wake of Operation Banshee, crystalised cocaine came into the picture and before long Blanco was back in the US flooding Miami with a steady flow of blow.

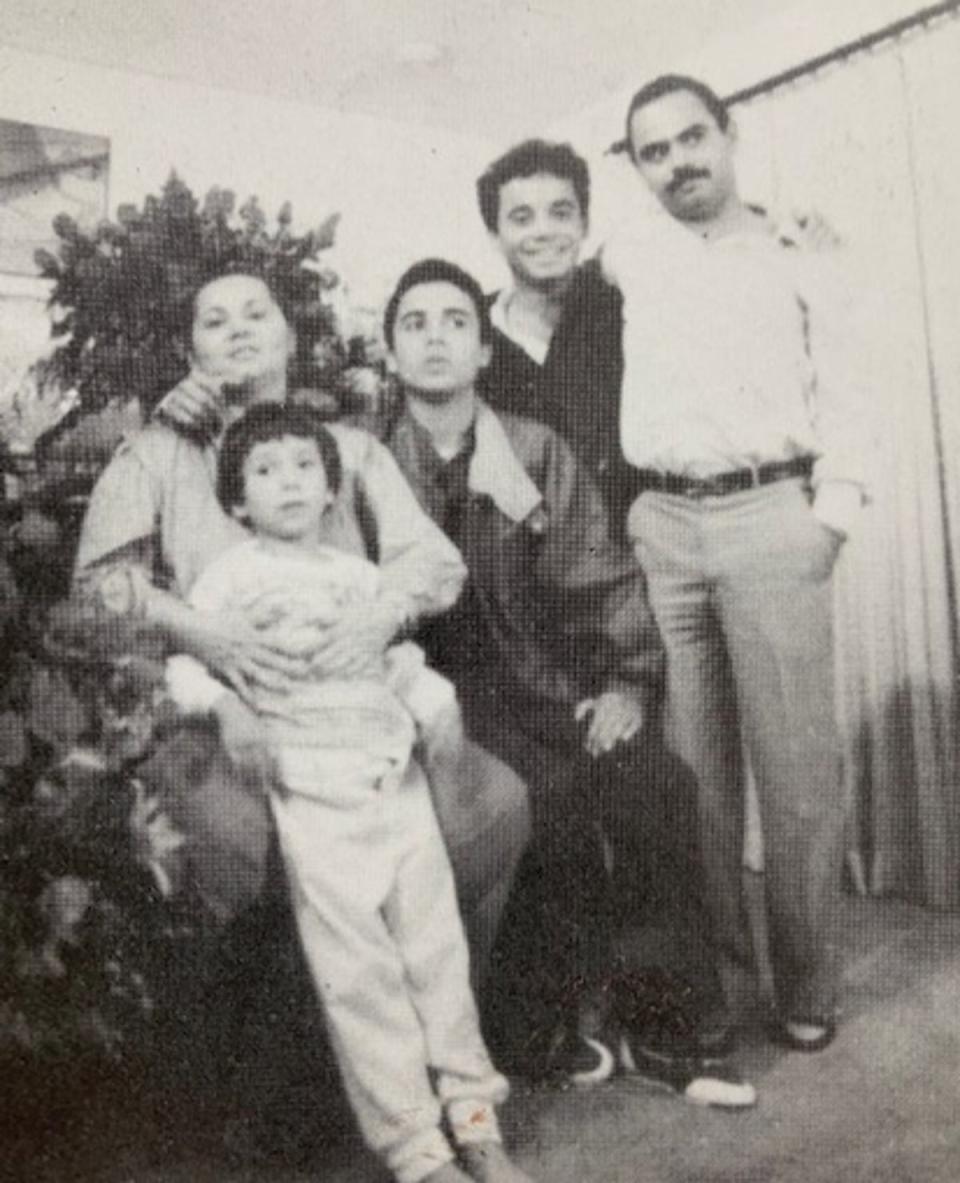

Fast-forward to the early 1980s when Corleone Blanco was growing up in California, hiding out in Morgan Hill, living a life disguised as a regular kid watching He-Man, not Al Pacino. His three older brothers Uber, Dixon and Osvaldo were running the family business from Miami, San Francisco and Beverley Hills.

“She was already such an entity that she was Medellin cartel, but she was the Queen. She didn’t have to listen to Pablo, she didn’t have to bow down to anybody because she gave them all their first routes,” he recalled.

The chameleon had not been seen or heard for the better part of a decade. She could gain or lose 30 pounds, change the colour of her hair, look rich or haggard, mesmerise as a Colombian Queen or pass as a middle-aged, American soccer mom from the suburbs.

But by 1983, the DEA and her enemies began closing in through a combination of luck, informants among her ranks, and, in particular, two younger women.

“What changed was her taste for violence. She wasn’t really taking care of business the way she should, or could, or had in the past,” said Palombo.

Out of the blue, the Miami DEA office was called by a worried mother that her very beautiful, very young, and very white, daughter was dating a Hispanic-looking drug dealer with a seemingly endless supply of cash: Uber Blanco.

It was the DEA’s first line on Blanco since the 1970s and first hint that Blanco’s sons, who were too young during Operation Banshee a decade earlier, had grown into the business. Six months later they got another break with the arrest of Geraldo Gomez, a Colombian determined to remain in the United States for his American-born son.

By sheer muscle memory, Palombo mentioned Blanco to Gomez, who was facing 10 years and deportation. Not only did Gomez know La Madrina, but he was also friendly with the family from when he operated a mechanic in Colombia, servicing her vehicles and turbo-charging Osvaldo Blanco’s motorcycles. Even better, his cousin was dating Dixon Blanco at that very moment in San Francisco.

Palombo had his lead. Gomez was eventually placed in witness protection and hasn’t been heard from since. More would follow, like Max Mermelstein, a Jewish American smuggler who pioneered the cocaine pipeline from Medellín to Miami. He later fled the cartel’s $3m bounty on his head and went into hiding in witness protection.

“She was seeing the ghosts of people past, and she had a hell of a time sleeping at night. Max would tell us she would often times have these young females that she would employ to come and sleep with her; and then the actual sexual encounters with some of these females during some of the wild during the wild orgy parties that she threw in Miami,” Palombo said.

Enemies were also closing in. Palombo said Blanco had a hit out for her over the killing of a family member of Jorge Ochoa, another Medellin Cartel founder.

After fleeing Miami, Blanco blended into the Californian woodwork so seamlessly that Palombo looked right past at his first glimpse in the lobby of a Newport Beach hotel.

“When I first laid eyes on her she was dressed like an American middle-aged woman who was very fastidious about herself. She had a blonde coloured wig, very nicely manicured. Her features and everything were just very well-groomed, her dress, she just looked quite sharp,” he recalled

A of couple months later she was “180-degrees different”: dressed slovenly, hair combed with an egg beater, the colouring was terrible, and she had an overall haggard look.

“A chameleon that changes at will,” Palombo said. “As time went by and she became more paranoid, because she had to leave Miami because of the hitmen that were after her.”

Even with the walls closing in, Blanco almost escaped prosecution.

Stephen Schlessinger, who started as a young prosecutor in the Southern District of New York during Operation Banshee, found himself in Southern Florida when Blanco came to trial.

They didn’t have “drugs on the table”, and his case was based entirely on the recorded conversations between Blanco, her three sons and the informant, Gomez, who led to the DEA’s first in-person glimpse of Blanco in the United States.

“The case proceeded without a gram of cocaine or a penny of drug proceeds. It was basically a drug conspiracy and the proof was just this talk. I mean it was all talk. “, Schlessinger told The Independent.

All they had were taped conversations that would have to be narrated and interpreted by the case agents and experts in drug lingo, essentially translating both Spanish and euphemisms to the jury.

It was not an overwhelming case. Schlessinger considered, but rejected, bringing in the indictment from Operation Banshee, but the case was too old and the physical evidence couldn’t be found. The past, the murders, none of that was prosecuted in her first trial. That would come later.

To this day, Schlessinger doesn’t know how she didn’t walk.

“We got up and we had two days of trial, which consisted mostly of my ‘walking the dog’, I was just in there wasting time and beating around the bush. We were preparing to put these tapes on and explicate them the best we could,” he recalled.

“The morning of the third day of trial, her lawyer gets up and without any notice to myself, said ‘we’re going to plead to the indictment’. What the motive and thinking was I had no idea.”

Judge Eugene Spellman, since deceased, excoriated Blanco during sentencing, calling her the worst thing since Ma Baker, Schlessinger said. Spellman threw the book at her with the statutory maximum, which Palombo has recalled being 35 years.

There was confusion in the courtroom. The judge was vehement. Blanco, dressed in black and clutching Rosary beads and a bible, had no visible reaction. The defence side of the room turned white.

Schlessinger and Palombo, meanwhile, thought they did a great job and went for a celebratory lunch. They had caught their chameleon and now they had her locked in a jar.

As they were biting into their hamburgers, Schlessinger’s beeper began screaming: The judge wants to see you immediately.

“It was very eerie because I walked up to his chambers and there was absolutely nobody there. I walked in, there he was alone in his chambers, and he basically said, ‘well Steve, I made a mistake, I had a conversation… I promised 10 or 12 years. I just forgot about it’,” he said.

Apparently, Schlessinger said, the ageing judge forgot about a backroom deal he had struck not to sentence Blanco for longer than her three sons - Uber, Dixon and Osvaldo - were sentenced shortly before her trial began.

Schlessinger says he was asked to go along with changing the verbal sentence in the formal written judgement, with the judge adding it “could be very dangerous” for Blanco’s defence lawyers if they didn’t. Defence attorney Roy Black told The Independent in an email that he had nothing further to add to the public record.

Ultimately, Schlessinger said they were given a choice – accept the sentence or go back to trial.

“There was no question… It was really no choice. It was not a strong case. Particularly against her. The sons, the conversations were a little more coherent, they were a little more incriminating, but against her, it was a jumble, a word salad,” he said.

“We were outraged by the whole thing. Looked at as a whole, the whole thing was an epitome of South Florida justice in the early 80s.”

While serving her sentence, state prosecutors built multiple murder cases and it looked like the rest of her days would be spent behind bars, or perhaps in an electric chair. But she struck another deal after secretaries in the Miami-Dade state attorney’s office were embroiled in a phone-sex scandal with their key witness, Blanco’s favourite hitman, Jorge “Rivi” Ayala.

She pled to three second-degree murder charges in 1998 and was out by 2004, when she was deported to Medellin. She lived another eight years until her assassination in 2012 – far longer than anyone expected.

The common theory is that it took her enemies eight years to catch up to her. It’s one Schlessinger believes credible, the only surprise being it didn’t happen earlier. Three of her four sons had all been killed after completing their sentence and returning to Colombia.

Palombo, dusting off his investigator’s eye, thinks otherwise. To him, it’s puzzling why she didn’t pay the ultimate price, like her sons, as soon as she returned to Medellin, where she lived a public life in a fancy neighbourhood. If someone wanted to avenge a lost loved one, it wouldn’t take eight years to find her.

“She wasn’t hiding. Not at all. She was killed at the marketplace, the butcher shop, and according to my sources, she lived a well-respected life in the community. She was supposedly very benevolent to the downtrodden and that may have been a reason that a lot of people didn’t bother with her,” he said.

#CartelCrew's Michael Blanco's lived life to the fullest and growing up in Medellin, Colombia comes with stories you can't forget!

Catch the return of @CartelCrew MON OCT 7 at 9/8 on @VH1! pic.twitter.com/0AJsQrdf6S— VH1 (@VH1) September 18, 2019

Another reason, he speculates: “There’s nothing worse as far as the criminal community as when somebody turns into an informant.”

After decades of slipping DEA’s net, blending into the background, refusing propositions to turn on the cartels, and serving her time, would The Cocaine Godmother turn state’s witness? Follow the timing, Palombo says.

Blanco was killed on 3 September 2012, at the age of 69. She was survived by her youngest son, Michael Corleone Blanco, also known as Michael Corleone Sepulveda after his father Dario Speulveda.

At the time of his mother’s death, he had been under house arrest since being arrested on 12 May, 2011, on two felony counts of cocaine trafficking and conspiracy to traffic in cocaine, according to The Miami New Times.

Blanco Speulveda did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

Since his mother’s death, Blanco has said in interviews he left the family business. He’s a star of the VH1 Cartel Crew reality series, which has run for three seasons since 2019. His wedding was featured in a 2021 episode and he now has children of his own to care for.

Ahead of the show’s debut, Blanco Speulveda appeared on the podcast of hip hop artist Bern and spoke about leaving the life behind, not living in fear, and launching businesses like Pure Blanco, a street ware company billed as “Billionaire Cartel Lifestyle Brand” in fashion, film, music, licensing, and cannabis, like the La Madrina Wake N Vape Collection to “taste the 80s”.

“My mother taught me to be a chameleon,” said Blanco.