Conservative SCOTUS Almost Entirely Ignores Pregnant Patients In Emergency Abortion Arguments

The Supreme Court heard heated arguments on Wednesday over whether states can criminalize life-saving, stabilizing abortion care in emergency medical situations.

The arguments, a consolidation of Idaho v. United States and Moyle v. United States, focused on Idaho’s near-total abortion ban, which first went into effect in August 2022. The justices debated whether the narrow exceptions in Idaho’s ban override federally mandated requirements for physicians under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. EMTALA requires hospitals that participate in Medicare — the majority of hospitals in the country — to offer abortion care if it’s necessary to stabilize the health of a pregnant patient while they’re experiencing a medical emergency.

The arguments highlighted the debate happening across the country since the Dobbs decision repealed Roe v. Wade: Are post-Dobbs abortion bans operating smoothly, or have they turned reproductive health upside down, forcing physicians and patients into impossible, often deadly, situations?

The Supreme Court case focuses on one of the Idaho ban’s three narrowly defined exceptions: when an abortion is “necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman.”

Federal law states that physicians are legally required to offer abortion in that scenario, but Idaho’s law is so narrow that it only allows physicians to perform an abortion when death is imminent. Those added delays could leave patients with long-term health conditions such as uterine hemorrhage (requiring a hysterectomy) or kidney failure that requires lifelong dialysis — if the procedure is performed in time to save their lives in the first place.

The outcome of the case wasn’t immediately clear following arguments with the court’s conservative supermajority of six justices potentially split and the three liberal justices in clear opposition to Idaho’s position. Justice Amy Coney Barrett was the lone conservative to express any seeming opposition to Idaho during arguments.

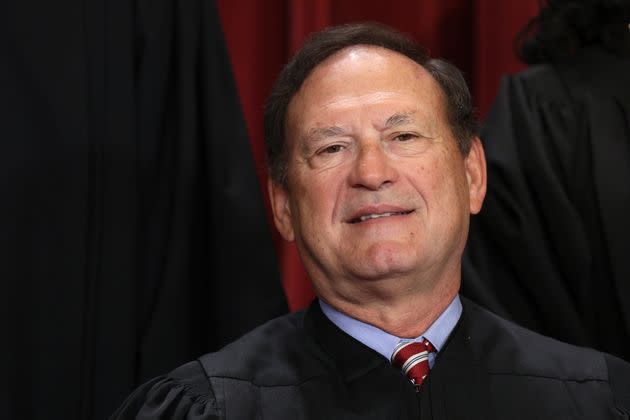

Meanwhile, the other conservative justices on the court were more interested in focusing on everything but pregnant people and the issues Idaho’s abortion ban has created for physicians on the ground. Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh concentrated on the spending power of the federal government in these scenarios and the mental health exception for abortion care in emergency medical situations — even though Idaho never raised questions about the spending power in the lower courts.

“Does the term health in EMTALA mean just physical health, or does it also include mental health?” Alito asked Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who presented arguments on behalf of the federal government. The question hints at one of the major arguments of the anti-abortion movement, which claims mental health exceptions are used as a loophole for women to get abortion care.

Prelogar said that “EMTALA could never require a pregnancy termination as the stabilizing care” for mental health emergencies because abortion was not the standard of care for medical health. She added that it would be “incredibly unethical” to terminate a pregnancy in that situation. Under EMTALA, a pregnant person needs to provide consent to receive an abortion in an emergency medical situation. In the situation Alito was describing, a woman would likely not be able to give consent, Prelogar pointed out.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor focused on whether EMTALA, a federal regulation, preempts state law — a critical point that the court spent a large amount of time on. Under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, federal law by default overrides state law. But the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision left regulation of abortion to the states.

“What you’re saying is that no state in the nation — and there are some right now that don’t even have that as an exception to their anti-abortion laws — is that there is no federal law on the book that prohibits any state from saying, ‘Even if a woman will die, you can’t perform an abortion,’” Sotomayor said.

Josh Turner, Idaho’s chief of constitutional litigation and policy arguing on behalf of the state, said that EMTALA does not preempt state law, but federal law does not have a standard of care.

The liberal justices also homed in on the very real medical emergencies that pregnant patients face and how the denial of critical abortion care, as practiced under Idaho law, harms them.

Justice Elena Kagan pressed Turner on whether abortion is the standard of care when “the woman’s health is in peril,” like when a woman faces the loss of her reproductive organs and her future ability to have children.

“That is the category of cases in which EMTALA says, ‘My gosh, of course the abortion is necessary to make sure no material deterioration occurs.’ And yet Idaho says, ‘Sorry, no abortion here,’ and the result is that these patients are now helicoptered out of state,” Kagan said.

Sotomayor interjected and used the example of a woman in Florida who, in 2022, suffered preterm premature rupture of membranes, or PPROM, resulting in “the real medical possibility of experiencing sepsis and uncontrolled hemorrhage.”

“This was a real woman,” Sotomayor said. “She was discharged in Florida because the fetus still had fetal tones. And the hospital said, ‘She’s not likely to die, but there are going to be serious medical complications.’ The doctors there refused to treat her because they couldn’t say she would die.”

The woman in Sotomayor’s story, Anya Cook, miscarried soon after and was rushed to the hospital with hemorrhaging blood.

In another example, Sotomayor presented the case of a woman who was diagnosed with PPROM at 14 weeks and denied an abortion. That woman eventually delivered the baby at 27 weeks; the baby died, and the woman was forced to have a hysterectomy.

Sotomayor then pressed Turner on what guidance Idaho gives to doctors in such cases. Turner said that such decisions are “very case by case.”

“That’s the problem,” Sotomayor said.

“I’m kind of shocked, actually. Because I thought your own experts had said that these kinds of cases were covered, and you’re now saying you’re not?” Barrett interjected. When Turner tried to respond, Barrett said he was hedging over what type of care would be covered under Idaho law.

Barrett continued to press Turner on whether doctors who followed guidance from the Idaho Legislature on the state law could be prosecuted if a prosecutor disagreed about the doctor’s judgment in providing abortion care during a medical emergency.

“That is the nature of prosecutorial discretion,” Turner said.

Where the liberals and Barrett did discuss the real-world effects of Idaho’s position on pregnant women, there was one lone moment where the other conservatives brought up the interests of the patient. But it wasn’t the life or health of the pregnant woman that concerned them.

In a particularly heated exchange, Alito questioned Prelogar about the inclusion of protections for the “unborn child” in EMTALA.

“Isn’t that an odd phrase to put in a statute that imposes a mandate to perform abortions? Have you ever seen an abortion statute that uses the phrase ‘unborn child,’” he asked.

Congress included that phrase because some hospitals in the 1980s refused life-saving treatment to women when “the woman was not in grave danger, but the fetus was in distress,” Prelogar replied.

“But what it doesn’t suggest is that Congress simultaneously displaced the independent preexisting obligation to treat a woman who is herself facing grave and life-threatening consequences,” she added.

Alito did not relent. Reading through the statute, he argued that “the plain meaning” of the law meant that hospitals “must eliminate the immediate threat to the child.”

“But performing an abortion is antithetical to that duty,” Alito said.

“The statute did nothing to displace the woman herself as an individual with an emergency medical condition when her life is in danger or when her health is in danger,” Prelogar replied.

Alito eventually claimed that the “only way” Prelogar could disprove his argument that the “unborn child” is of paramount concern in all situations under EMTALA is to use the word individual, which “is defined to exclude the unborn child or fetus.”

Prelogar again explained that when Congress included the phrase “unborn child” in EMTALA, it was to provide a duty for hospitals to treat pregnant women with conditions that didn’t threaten her own life or health but did threaten that of her fetus.

“To suggest that, in doing so, Congress suggested that the woman herself isn’t an individual — that she doesn’t deserve stabilization — I think that that is an erroneous reading of this statute,” Prelogar said.

“Nobody is suggesting that the woman is not an individual when she doesn’t deserve stabilization,” Alito said before Prelogar cut him off.

“Well, the question would be that the state of Idaho is declaring that she cannot get the stabilizing treatment even if she is about to die. That is their theory of this case and this statute, and it’s wrong,” Prelogar said.

The justices also brought up the impacts of a potential ruling outside Idaho. States including Texas and South Dakota currently have near-total abortion bans in effect that have exceptions for the life of the pregnant person but not the health of the pregnant person — directly conflicting with EMTALA. There have been dozens of reports of pregnant women across the country — in Texas, Florida, Oklahoma and elsewhere — who were denied care because they weren’t close enough to death to require medical intervention.

Idaho, meanwhile, has lost nearly a quarter of its OB-GYNs and 55% of its maternal-fetal health specialists. Three maternity wards have shut down, making the state one of the largest maternal health care deserts in the country. This is what will likely happen to other states with narrow abortion ban exceptions if the Supreme Court rules in favor of Idaho.

“Any decision that falls short of guaranteeing patients’ access to abortion care in emergencies — as has been law for nearly 40 years — would be catastrophic,” Alexis McGill Johnson, president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, said in a statement ahead of Wednesday’s arguments. “Unless the Supreme Court is willing to let pregnant people die or suffer grave health complications, it must ensure federal law continues to protect emergency abortion care.”

The Department of Justice sued Idaho when the abortion ban first went into effect in 2022 because the state law is in direct conflict with EMTALA. The case could have deadly consequences for people with the capacity for pregnancy, depending on what the court decides. A ruling in the case is expected sometime in June.