Death of Marine commander scarred by 1983 Beirut bombing serves as reminder of risks US troops stationed in Middle East still face

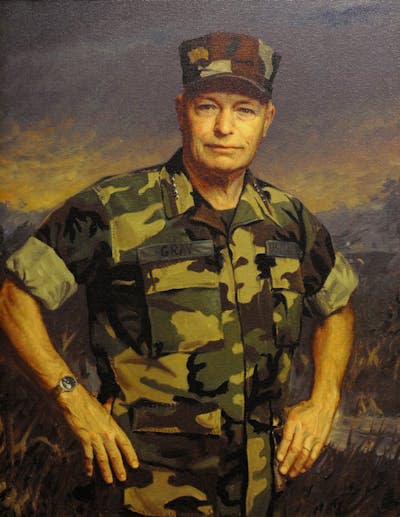

Gen. Alfred M. Gray Jr., who died on March 20, 2024, at the age of 95, was seen as a legend for his heroism in combat.

But despite his military success, Gray, who went on to serve as the 29th commandant of the Marine Corps from 1987 to 1991, will always be associated with one of the darkest days in U.S. military history: the Beirut barracks bombing on Oct. 23, 1983. The terrorist attack killed more than 300 people, including 241 U.S. service personnel under Gray’s command, although he was stateside at the time of the attack.

As a scholar currently doing research for a project on that attack, I can’t help but note that Gray’s death comes amid a surge of violence in Lebanon and at a time when U.S. troops stationed in the Middle East are again being targeted by Islamist groups funded by Iran.

Marines in Lebanon

Gray’s experience with U.S. involvement in Lebanon underscores the dangers American troops face when deployed to volatile areas.

On June 4, 1981, he was assigned to command the 2nd Marine Division and all the battalions that went into a war-torn Lebanon from 1982 to 1984.

By then, the country’s civil war had been raging for six years. It began on April 13, 1975, and, similar to the upsurge in violence in Lebanon now, it was fueled by events south of the country’s border.

Palestinians expelled or fleeing from what became Israel in 1948 ended up as refugees in neighboring countries, including Lebanon. In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization was founded to represent the Palestinian people and fight Israeli occupation. By the mid-1970s, over 20,000 PLO fighters were in Lebanon and launching attacks on Israel.

But their presence in Lebanon led to violence between Lebanese Christians and Lebanese and Palestinian Muslims. While some in Lebanon wanted peace with Israel, others wanted to fight for the Palestinian cause.

Several gruesome massacres marked the first five years of the civil war. In 1982, Israel launched Operation Peace for Galilee, invaded Lebanon and occupied Beirut with the intention of destroying PLO forces.

The Lebanese authorities called on Western powers for help. In August 1982, the governments of the United States, France, Italy and the U.K. created a multinational peacekeeping force designed to restore peace and stop the fighting between the Lebanese, Palestinians and Israelis.

It was not the first time that Lebanon had asked the United States for help. On July 15, 1958, 1,700 Marines arrived in Beirut ready for combat as hostility erupted between Christians and Muslims. However, unlike 1958, the fighting of the 1980s was much more violent, and entrenched war had already been raging for over five years.

While most Lebanese welcomed the foreign peacekeepers, many opposed them and saw them as a Western colonial interference in Muslim-majority countries.

Day of attack

Then, on Oct. 23, 1983, witnesses reported seeing a yellow Mercedes truck speeding toward the barracks that housed the American service members. It carried 10 thousand pounds of explosives, and the force of the explosion flattened the building, killing 220 Marines, 18 U.S. Navy sailors, and 3 U.S. Army soldiers.

Minutes later, a similar attack took place in the French quarter, resulting in the deaths of 58 French paratroopers.

To this day, this event remains the deadliest single-day attack for the United States Marine Corps since the battle of Iwo Jima in 1945.

The Islamic Jihad, a pro-Iranian Shiite group, claimed responsibility for the attacks.

Gray, a two-star general, was alerted about the attacks just after midnight. The Beirut barracks bombing was a personal affair for Gray; his troops were in Lebanon, and he had visited them just months before the attack.

After the bombing, Gray attended over 100 funerals of the service members killed. He also offered his resignation over the incident – the only senior officer to do so. His request was declined.

Lessons from 1983

One could draw many parallels between the Beirut barracks bombing of 1983 and current events.

In August 1982, President Ronald Reagan expressed his grave concern over Israel’s conduct in Lebanon and warned Israel about using American weaponry offensively. In a phone conversation with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Reagan described Israel’s siege of Beirut as a “holocaust.”

To respond to this human crisis, the multinational peacekeeping force was tasked with evacuating PLO fighters outside Lebanon into Tunisia. Once this mission was accomplished, the U.S. troops pulled out of Lebanon.

However, the escalation of violence prompted their return. In fact, while Palestinian fighters were evacuated, their families stayed behind. Then, after the assassination of Lebanese President-elect Bashir Gemayel on Sept. 14, 1982, the Christian Phalangist militia entered the two refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila and killed over 2,000 Palestinian civilians. Israel was considered indirectly responsible for these massacres.

From that moment, U.S. troops were no longer perceived by Muslim militias as peacekeepers but as allies to Israel and a partner in crimes committed against Muslim civilians.

Forty years on, American troops in the Middle East remain a target for much the same reason. And as a result, U.S. service members have seen increased hostility against them in the region.

There is another parallel: Just as the group that claimed responsibility for the 1983 Beirut attack was being financed by Iran, so too today are the groups responsible for attacking U.S. bases across the Middle East.

Spurred by failings involved in the 1983 bombing, Gray sought to reform the Marine Corps after the tragedy, with greater focus on intelligence-gathering and understanding enemy groups.

And while it is right to celebrate a high-ranking military officer who dedicated his life to service, it is equally important to consider the causes that led to the deaths of those under his command – and the fact that many of the factors contributing to the 1983 terrorist bombing continue to exist today.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Mireille Rebeiz, Dickinson College

Read more:

Mireille Rebeiz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.