The Faces Behind Louisiana’s Fight To Say Gay

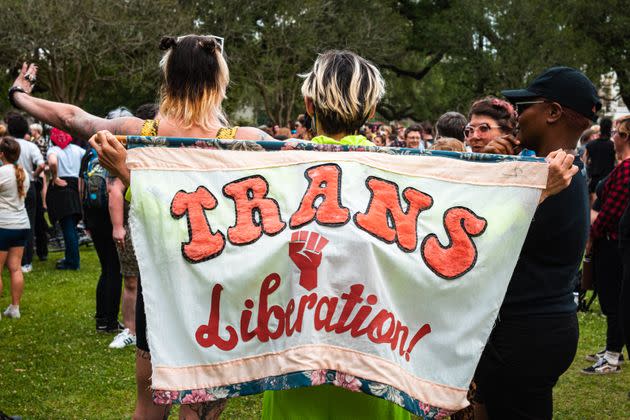

Participants listen to speakers at the Transgender Day of Visibility rally held March 31 in Washington Square Park in New Orleans.

Mostpeopledon’t know that you can just go testify at congressional hearings. You don’t have to be “important” or register in advance. When I went to cover the hearing for Louisiana House Bill 466 — legislation that would prohibit teachers from discussing matters of gender and sexuality with students in public schools — the people I saw offering testimony for Louisiana’s version of “Don’t Say Gay” were just other concerned citizens like me. So I decided to speak.

My testimony centered on my experience as a former educator. I explained that I had not been officially out when I was a teacher over a decade ago. More specifically, I wasn’t out to the administration. But I didn’t hide my queerness from my students. I never had to come out to my students — they just knew.

I recounted how my fourth grade and fifth grade students would often ask if I were a boy or a girl. I always hedged, countered those questions with other questions like, “Well, what do you think?” And when they said, “You don’t really seem like a boy or a girl,” I just smiled and told them that they were smart.

Many students came to me with their own gender dilemmas. Some of them were as simple as needing to talk about how they didn’t want to have long hair, even though they were girls. And some of them were as complex as wondering what it meant that they were a boy with a crush on a boy. I was not perfect as a teacher, but I think my students knew they could come to me, not for answers, but for acceptance.

If HB466 passes, those conversations — which are often crucial to a student’s well-being — would become illegal.

“Basically, this legislation will codify an already unspoken process of gaslighting trans kids out of existence,” Augistina Johnson, a 27-year-old organizer with the Real Name Campaign, a grassroots trans advocacy organization in New Orleans, tells me.

“That is something I experienced as a kid, where I grew up in New Orleans,” Johnson says. But instead of scaring her out of resistance, Johnson’s experience as a trans youth in Louisiana made her into an activist. I can relate. My own experiences as a queer educator combined with giving testimony and talking to others at the hearing inspired me to connect with people who are committed to protecting queer youth in Louisiana.

“How can any trans person stay in school if you’re going to literally force us out?” Johnson wonders.

Ed Abraham, a 28-year-old organizer also with the Real Name Campaign, commiserates. “We deserve more than to just survive,” he says. “Not killing ourselves doesn’t have to be what trans success looks like.” Abraham cites some of the harsh realities that LGBTQ+ youths face: anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and the risk of dropping out of school.

Unfortunately, there aren’t many statistics on how many LGBTQ+ students drop out of school, but research does give us a startling glimpse into the mental health challenges that queer youth are dealing with. According to The Trevor Project, 45% of the 34,000 LGBTQ+ youth surveyed attempted suicide in 2022. Fewer than 1 in 3 participants in the study felt they had a supportive home environment.

LGBTQ+ kids in America face massive mental health challenges. Many don’t have support at home — so they need support at school.

In other words, LGBTQ+ kids in America are facing massive mental health challenges and many don’t have support at home — so they need support at school. They need it, not just to come to personal terms with who they are, but in order to survive within a system stacked against them. Citizen after citizen testified that their greatest fear was that the legislation would increase the risk of suicide. “If you pass this bill,” one person said, “the blood will be on your hands.”

Bills such as HB466 would also effectively prohibit the more formal support structures designed to protect children, like GSAs — genders & sexualities alliances — which are student-run, teacher-supported organizations in schools meant to help students of any gender or sexuality find resources, support and camaraderie. Research shows GSAs may help make schools safer and contribute to a positive school environment — for all students.

Mel Manuel, a 39-year-old public school teacher in Louisiana who is currently running for Congress, sponsors the GSA at their school. “This is going to basically cancel GSA because, even though it doesn’t outright exempt students from talking to each other about gender identity and sexual orientation, it prohibits teachers from doing so and you need a teacher sponsor to form a GSA.”

Mel Manuel teaches in a conservative Louisiana parish and they’ve seen firsthand how important genders & sexualities alliances can be in children's lives.

Manuel teaches in a conservative Louisiana parish and they’ve seen firsthand how important GSAs can be in children’s lives. “For some kids, that’s the only space that they have where they can be openly wherever they are,” Manuel says. “A large percentage of them have told me directly that they attempted suicide or thought about suicide.” Manuel says they’re scared about what could happen if those already at-risk kids couldn’t find safe spaces at school.

Nathalie Nia Faulk, a 32-year-old cultural organizer and healing justice practitioner in New Orleans, tells me GSAs were one of the first places she felt safe as her most authentic self as a teenager and she’s fighting against HB466 so other young people in Louisiana have the same opportunity. “I have survived this long because I was able to be in my transition and I’ve been able to be in spaces and be seen in my gender,” she says.

At the root, what queer people in Louisiana are fighting for right now is the simple right to exist and be recognized. When Maxwell Cohen, aka Big Gay Baby, a 27-year-old drag queen in New Orleans, gave testimony with a blue face adorned with stars, the crowd — and the media — went wild. A mom handed them her phone afterward and asked them to FaceTime with their children. “My kid wants to show you that they’re wearing the same shirt as you,” the mom told Cohen. The shirt read, “Trans rights are human rights.”

“This kid’s face lit up looking up at me and I was like, I know what you’re feeling. I know what it’s like to look at a drag queen for the first time,” Cohen tells me. These seemingly small moments of mutual recognition can mean so much to children starving for acceptance. But the consequences of not having those moments are dire.

Everyone I spoke to at the hearing, from middle-aged suburban moms in pearls to social psychologists, pointed out that the dire statistics associated with being queer in the South are the result of stigma. “The far right will point us in the fact that we do survival sex work and have a higher risk of struggling with substance abuse and we have higher rates of being incarcerated and they say it’s because we’re trans or queer, but in fact, it’s because of all the stigma they keep throwing at us,” Cohen says.

Those engaged in the fight to say gay in Louisiana are struggling within the context of that stigma — and it is a fight that often requires great personal sacrifice. Manuel resigned their position as a teacher to run for Congress. No, there’s no law that prohibits educators from also being public officials, but Manuel knew they could not engage fully with LGBTQ+ legislative issues without facing professional consequences. “If I was going to be at my school, I would have to censor myself,” Manuel tells me. “I don’t want to have to tiptoe.”

Advocates and activists also face threats to their personal safety. One source I spoke with for this article requested that no images of them appear in the article. “I’m scared,” they told me in an email.

Frankly, I am too. A conservative representative posted my testimony on Twitter, and I was terrified by the vitriol that ensued from my essentially innocuous talking points. Some Twitter users made shocking assertions that I am a pedophile and a groomer, and several posted threats of bodily harm. It’s impossible not to feel fear in the face of such hate.

If you’re wondering why anyone would testify only to be lambasted on the internet, spend all their free time organizing, or give up a job they love to become a public target, well, that’s exactly why. Fighting for the next generation of LGBTQ+ people to be seen as human and valid is worth it. And facing the stigma head on makes it clear that the stakes of bills like HB466 are truly life and death. But the stakes are also love and belonging.

Every step we take together makes room for more steps to become possible. “We have always been here. We will continue to be here,” says Pearl Ricks, the executive director of the Reproductive Justice Action Collective, a network of Southern activists. Ricks says they love connecting with young people as a way to share optimism. “They exist with a little more wiggle room than I started out with,” they say. That wiggle room opens new spaces of possibility for all of us.

HB466 passed in the Louisiana House of Representatives on May 9. The bill is currently being read by the state Senate and is expected to be heard by the Senate this month, which means that proponents and opponents will be able to testify in front of lawmakers. If it passes there, HB466 will then be sent to Gov. Bel Edwards (D). Edwards has not said explicitly whether he would sign the legislation if it lands on his desk.

However, he has raised concerns about the recent onslaught of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Louisiana, saying in a press conference last week that he believes it could increase the risk of suicide for trans youth. “Members of this community believe they’re being attacked for who they are,” Edwards said in the press conference.

The acts of being seen and of speaking out in themselves accomplish some of the work that needs to be done. Of course we need allies in our struggle for liberation. Of course we need legal protections. Of course we need support. But more than anything, perhaps, what all queer people of every age need is proof that it is possible to survive and thrive. We need to see each other. As Ricks says, “It helps us understand that we exist permanently, we are loving permanently.”