Famed Manitoba aviator Bob Diemert remembered as a pioneer who 'never stopped dreaming'

A Manitoba aviator who was famed for his restorations of old warplanes, and was even the subject of a documentary about his quest to design his own aircraft, is being remembered for his outside-the-box thinking and his drive to see projects through to their end — sometimes proving his doubters wrong in the process.

Carman's Bob Diemert, who died on Jan. 11 at age 85, is being remembered by people in the aviation community as a pioneer and even "a legend."

"He was kind, he had a big heart, he would do anything for friends and family," said his oldest daughter, Dianne Sauvlet.

"One of the smartest guys I knew — for aviation, he was all self-taught. He never went to post-secondary school for engineering or avionics."

Dianne Sauvlet with her father, Bob Diemert, after he received the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Medal on Nov. 28, 2022. (Submitted by Dianne Sauvlet)

Diemert was born in Morden, Man., in 1938, but was raised in Manitou and Winkler, before moving to Carman — a southern Manitoba town with a current population of just over 3,000 — in his early 20s.

He gained fame for restoring and later stunt-piloting a Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft for the 1969 film The Battle of Britain, Sauvlet said.

Diemert was also known in the aviation community for restorations of decades-old Japanese warplanes like the Mitsubishi A6M, better known as the Zero, and Aichi D3A, sometimes called the Val, said Sauvlet.

Decades after the Second World War, he ventured to the jungles of the South Pacific to find the remains of the planes, she said.

"Those would've been in there since … towards probably the end of the Second World War and he didn't go there until probably until mid-'60s," said Sauvlet. "The jungle in the South Pacific was not kind to those planes at all."

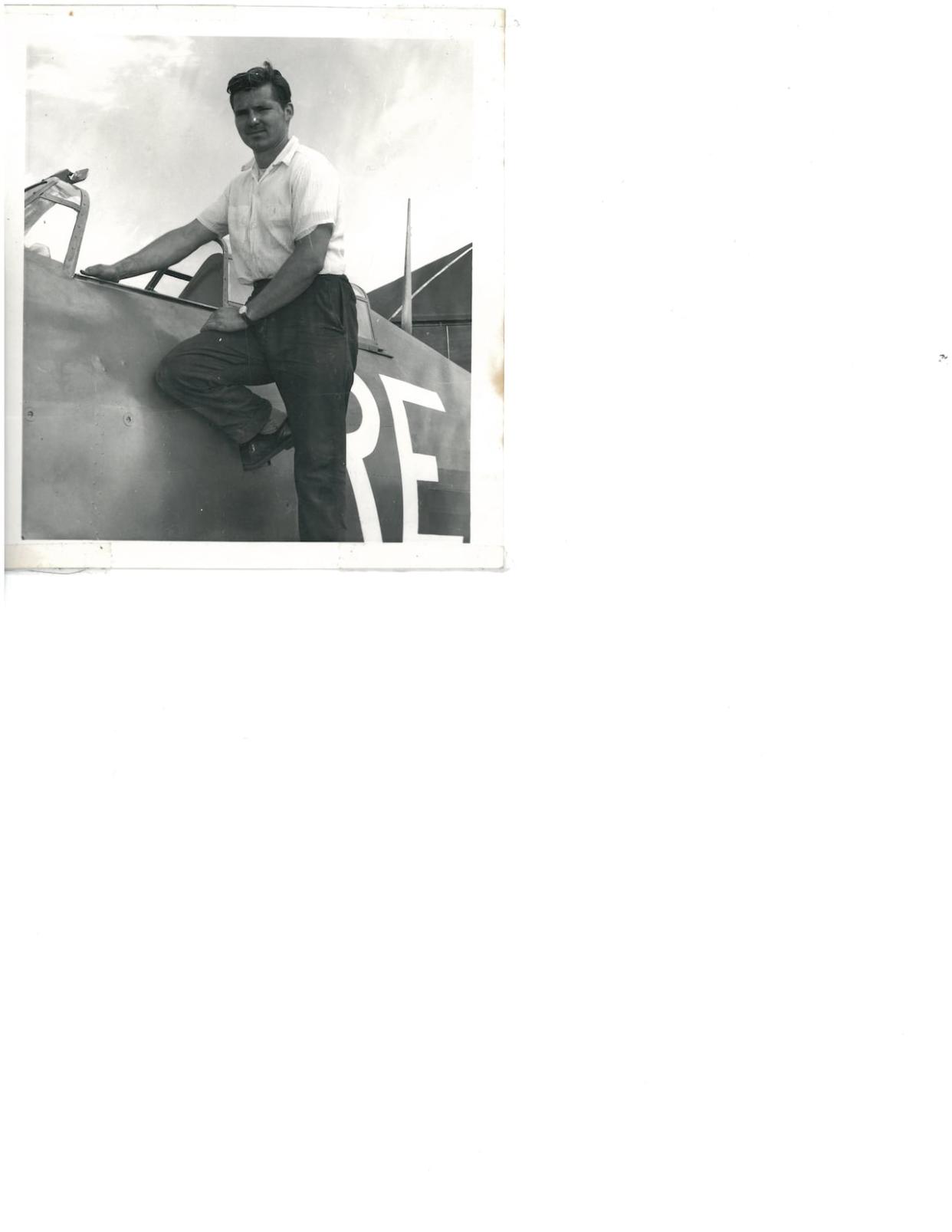

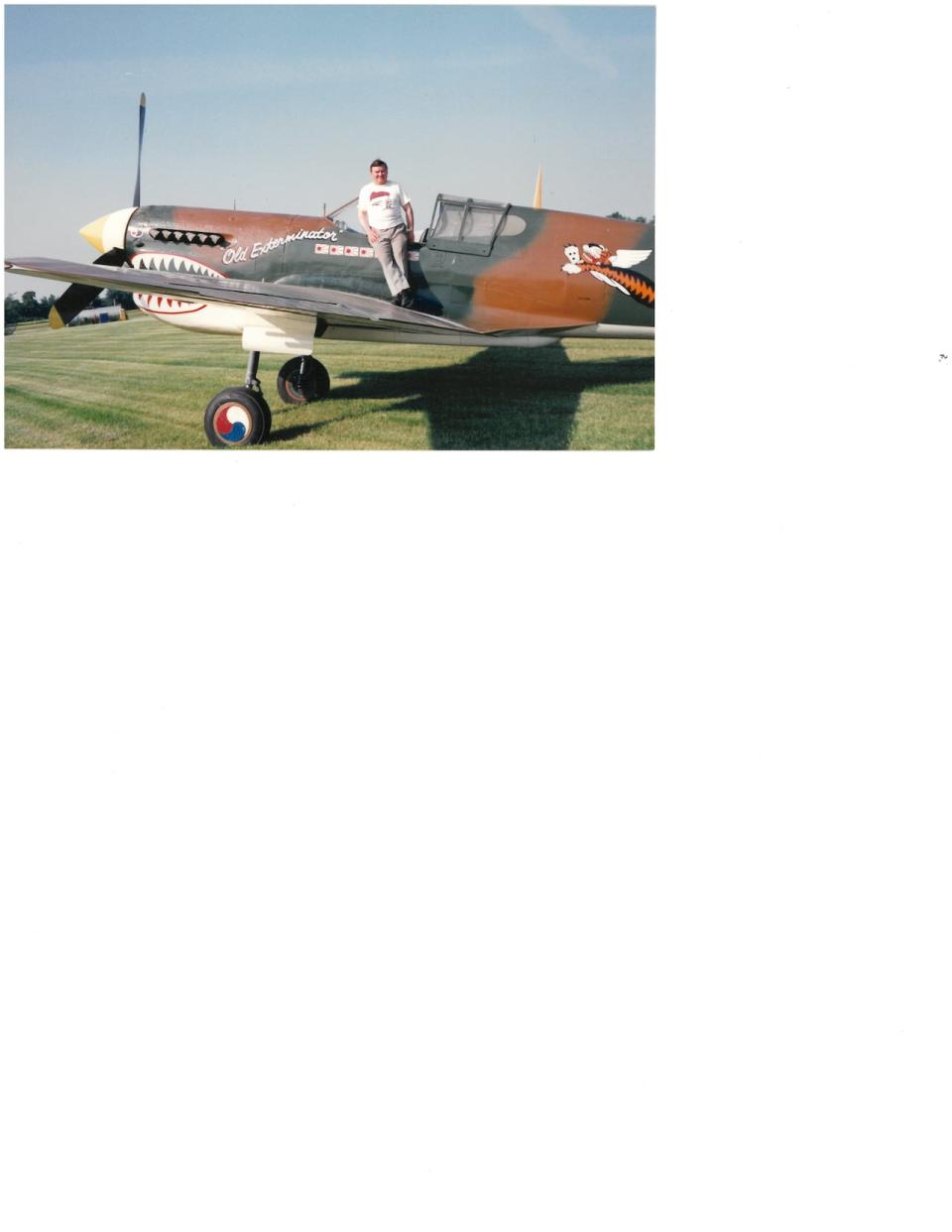

A family photo shows Diemert on a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. Diemert, who restored old warplanes, bought the plane from someone in Portage la Prairie, Man., according to his daughter. (Submitted by Dianne Sauvlet)

"For the Japanese planes, he actually had contacted somebody in Japan and he had somebody come over with blueprints for the Zero and the Val, and so that's how he was able to restore [them]," said Sauvlet.

The Val he restored was donated to an aviation museum in Ottawa. One of the Zeroes Diemert worked on with his friend Chris Ball was restored for a non-profit group that does historical air shows in Texas, according to Gerry Suski, another longtime friend.

The Defender

In the 1980s, he also worked on designing his own aircraft, which he called the Defender — the subject of a 1988 National Film Board documentary of the same name that revolves around his quest to not only build an aircraft, but to mass produce a cheaper alternative for the Canadian military.

Diemert built the aircraft — like his many other restoration projects — out of the hangars at Friendship Field airport in Carman, with some of its design plans even sketched out on the floor.

"He spent many, many days in Winnipeg at the Department of Transport offices, the military offices in Winnipeg — and federally — trying to convince them that his Defender should be looked at more seriously, but they wouldn't do it," Suski said.

"He didn't give up. He just kept on at it."

A photo of the test flight for the Defender, a plane Diemert designed himself, from the 1988 National Film Board documentary named after the aircraft. (National Film Board of Canada)

Diemert was trying to prove there was more to aerial combat than "who could fly the highest and the fastest," said Suski.

In addition to being relatively inexpensive, he thought the Defender would be able to fly low and be easy to arm, said Sauvlet.

The Defender Diemert built still exists in one of the Carman hangars, and there are hopes to one day make a Bob Diemert flight museum there, said Suski.

"When I talked to him about it the last time … he said, 'I'm not finished yet' — and that's why we haven't started anything in his honour."

'Bob would often prove people wrong'

Diemert prepared the third version of the Defender — in all its more than 300 kilograms of armour-plated glory — for its first flight in July 1986, but it couldn't ascend to the desired heights.

While the military never gave Diemert's project a serious look, Sauvlet said her father's "never quit" attitude is something that should inspire others.

"Just don't give up on your goals," she said. "He never did and he always saw a project through, and he just never stopped dreaming."

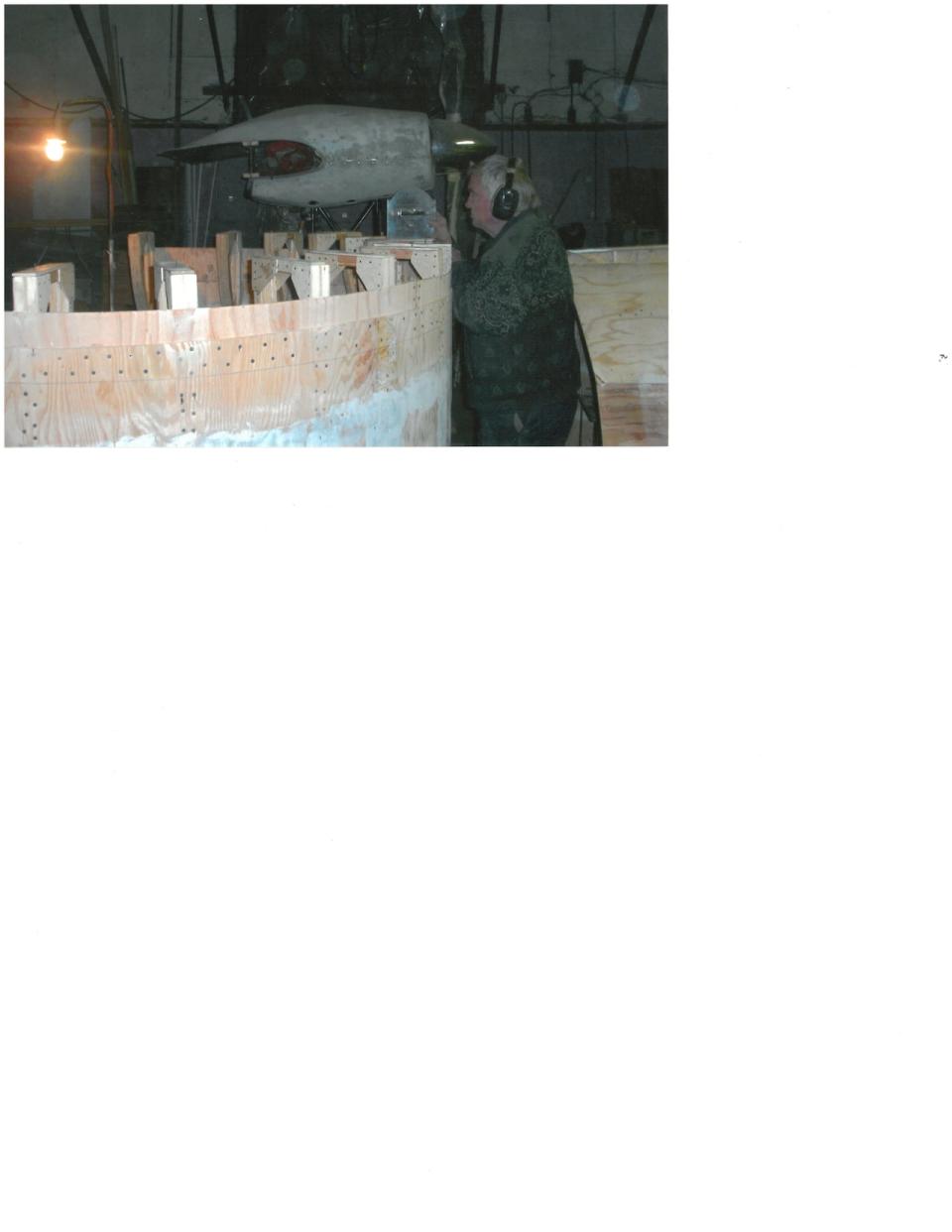

A more recent photo of Diemert working on a now unfinished project. Sauvlet said her father was always working and full of ideas, right up until his death. (Submitted by Dianne Sauvlet)

His efforts also inspired people like Mike Maskell, who first met Diemert over 40 years ago and later went from being a glider pilot to flying privately. He then became an aircraft maintenance engineer.

"I think Bob just allowed me to see a different side of aviation — things that are possible," said Maskell. "When others may say it's impossible, Bob would often prove people wrong."

Suski echoed that statement, saying Diemert was just "speaking a different language that people didn't understand."

"He proved a lot of people wrong. They thought he couldn't do a lot of things, but he did do a lot of things that a lot of other people didn't."