Genetic genealogy was key to the Byron Carr homicide investigation. Here's how it works

When Charlottetown police announced an arrest in the 1988 killing of teacher Byron Carr, they credited genetic genealogy as a "game changer" in the investigation.

Carr was strangled in his Charlottetown home on Nov. 11, 1988. The investigation was reopened in 2007, but solutions remained elusive until the spring of 2022, when new developments began to point to Todd Joseph Gallant, who now faces a charge of murder.

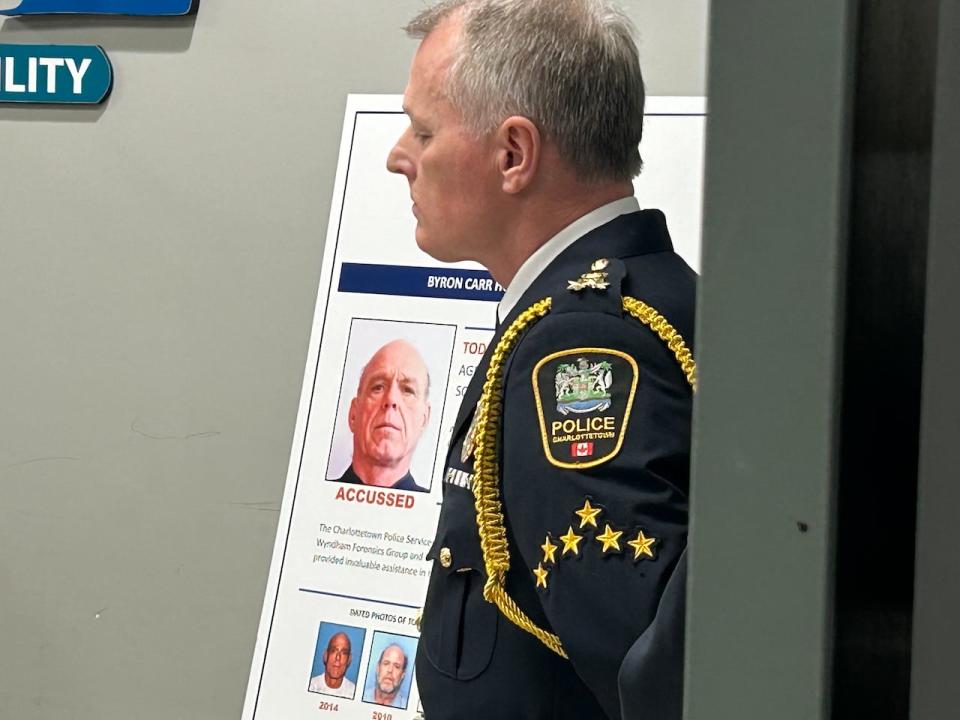

"Genetic genealogy is a game-changer in how we investigate major crimes. We're seeing some amazing results," Charlottetown police Chief Brad MacConnell said at the news conference announcing the arrest on Friday.

Police gathered DNA samples as part of their initial investigation 35 years ago, but were unable to find a match in databases of DNA records from convicted criminals.

Charlottetown police Chief Brad MacConnell has been at the forefront of the Byron Carr homicide investigation since it was reopened in 2007. (Laura Meader/CBC)

But genetic genealogy lets them look beyond the DNA records of criminals and into databases containing the details of millions of people who have never had an encounter with police.

MacConnell cited two databases in particular: GEDmatch and Family Tree DNA. Police use these files not to find the suspect, but to find relatives of the suspect.

There's still a great deal of both genealogical work and then investigative work that needs to happen in order to make the connection. — Nicole Novroski

GEDmatch has been used this way since 2018, and claims more than 400 cases have been solved with its help.

"The more information that's shared in those DNA data files, the closer in relatedness your profile is to theirs," said Nicole Novroski, a forensic geneticist professor at the University of Toronto.

"But there's still a great deal of both genealogical work and then investigative work that needs to happen in order to make the connection."

Science and old-fashioned detective work

It would be a rare case where genetic genealogy would point to a single person.

For example, if the system finds a 30-per-cent match, that would suggest it's a first cousin once removed of the criminal, or an uncle or aunt. Depending on family size, even this relatively close relationship could potentially point to a large group of people.

Nicole Novroski says Canada doesn't have laws or best practice guideline for the use of genetic genealogy in crime investigations. (Submitted by Nicole Novroski)

At that point, the investigation would return to more traditional police work. Who are the first cousins once removed, the uncles, the aunts? Where were they at the time the crime was committed, and could they potentially have a motive for the crime?

We do not yet know the connections Charlottetown police made to hone in on Todd Joseph Gallant, but MacConnell suggested it was a lengthy process.

"Over time you narrow your focus, seeing how people connect and families connect," he said. "There's no straight line to the finish."

'Humans are good'

Key to the success of this kind of investigation is the goodwill of millions of people who volunteer their information to police when they submit samples to genealogy sites.

There are no current laws in Canada regulating the use of genetic genealogy by police, said Novroski. People use services like GEDmatch and Family Tree DNA to learn more about their families. They can learn where their ancestors came from, and perhaps even who their ancestors were.

And when they do that, they are asked a question: Are you willing to allow police to use your profile in criminal investigations?

Millions have said yes.

"Innately, humans want to be helpful," said Novroski.

"Humans are good, so people are putting their information in there so they can contribute to the resolution of these crimes."

It's a decision that may sometimes upset other family members, she said, but many are taking the view that their family members must be held responsible for their actions.