We All Got The Beach Boys Wrong—This Film Gets Them Right

Perhaps no major band has ever been hounded by such a highly prescriptive sense of expectation as the Beach Boys. For millions of listeners, they were a group whose primary function—and job—was to deliver catchy hits of surf and sun, cool cars, and trips to the movies with your “steady.” Because that’s what they had done so well from their very first recordings.

The music within the grooves of those early records enveloped the listener in a gold and blue world of warmth, water, wakefulness, the possibility of the new day. The Beach Boys’ music spoke—sang—to joy, with songs that functioned as an open invitation to lend one’s own voice to them, never mind that they featured the harmonies of the gods. You simply felt good listening to the Beach Boys.

Then there are those in the know, who realized somewhere along the Beach Boys’ journey that this was music as adventurous as a dream. That idea of the oneiric state—and all the wonder to be sourced therein—is the key theme of directors Frank Marshall and Thom Zimny’s two-hour-long Disney+ documentary, The Beach Boys. It arises again and again, as if these Beach Boys were purveyors of the kind of clarity that originates with mystery, rather than singsong simplicity.

Documentaries can be tantamount to the feeling-out of a subject, in which we all learn more as we go along, with the movie doing so as well. Others have an agenda, something they want us to come away believing. What Marshall and Zimny’s film possesses is deep knowledge of its subject’s actual essence, which is different from how the Beach Boys are normally perceived by the public.

The movie is cognizant of where a lot of its viewers will be coming from. The Beach Boys of their earliest era—meaning the first half of the 1960s—are the Beach Boys most commonly called to mind. This was the time of the hits that married Chuck Berry guitar riffs with surf culture attitude and, as Brian Wilson affectionately relays in an interview clip, the vocal harmonies of the Four Freshmen.

Chances are high that if you love rock and roll, the Beach Boys were one of the first bands you fell for. You might have discarded them later, thinking them not hip enough—it’s hard to envision a with-it high school kid rockin’ out to “Surfin’ Safari” rather than The Dark Side of the Moon—but that might have been a you thing rather than a Beach Boys thing.

Rather, the Beach Boys were complicated artists who made sophisticated music that also just happened to be accessible for a lot of people. And it can take time—both with the passage of life, and time spent with that art—to hear what has always been there for the hearing.

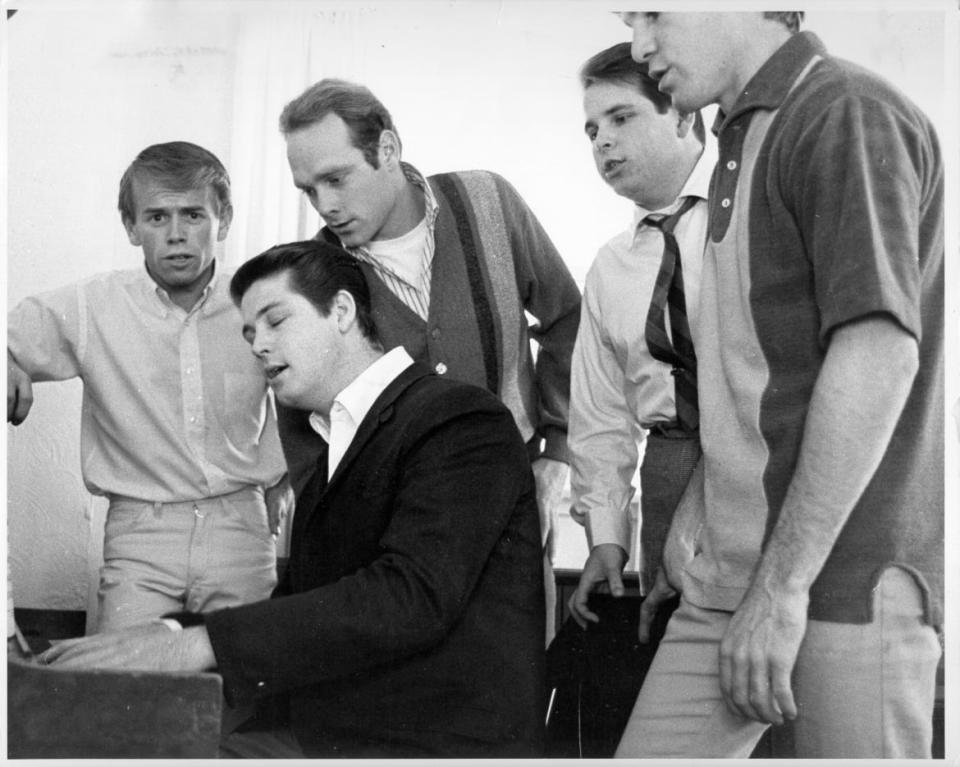

The film takes the form of an oral history, interspersed with vintage clips. The narration comes entirely from interviews, both in the present day and out of the archives. Most of the words are from the Beach Boys themselves: the three Wilson brothers, Brian, Carl, and Dennis, their cousin Mike Love, and family friend Al Jardine.

The focus is the 1960s. Save for the closing credits, we’re not doing “Kokomo.” The further focus is the music. How that music was first formulated, how it altered, the pitched battle between commercialism and art. It’s a story of personal growth and also the growth of a unit.

When Mike Love talks about the sublimation of the individual, what he also means is an emphasis on the collective. For just as the Beatles had their combined one-ness, so did the Beach Boys. These men took a creative journey together, and that journey is best told through the music that was created as a result.

Whenever there’s family, there’s family drama. That drama in The Beach Boys mostly has to do with Murry Wilson, father to Brian, Carl, and Dennis. He was vital to them “making it,” and then it was vital that he go when the abuse became too much, which we realize it had been all along.

You needn’t have eclectic musical interests to appreciate the lived-in shop talk that stirs the passions evident in the documentary. Brian Wilson comes across as an awesome music fan. He’s that guy dying to tell you about this new record he heard last night for the first time and how it blew his mind. Frankly, more people now should know about the Four Freshmen, who were responsible, in Wilson’s words, for his “entire harmonic education.”

We learn that the famous Beach Boy harmonies themselves were honed in the backseat on car trips and Christmas caroling parties at the Love house. We get input from other seasoned voices. Producer Don Was, for instance, uses the word “texture” in describing those harmonies, which is another central theme, the idea of the Beach Boys’ music as being almost somatic, something that you can feel on or under your skin, or that touches you more deeply.

We experience the Beach Boys’ music so readily in our bodies, though, that many people began to think that this was a group that couldn’t produce sounds for the head the way the likes of Bob Dylan, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, and the Beatles could. That was art. The Beach Boys were… oldies.

That notion is among the great misconceptions in all of popular music history, and it’s one this film—simply by telling a truthful musical story—redresses.

1966’s Pet Sounds has become beloved and it can sit comfortably in any hip record collection alongside Blonde on Blonde and Revolver, but its abrupt breakage from the Beach Boys’ “norm” created an asterisks effect at the time, like it didn’t count and we’re all allowed to go crazy once.

Then there is the legend of perversity that is the Smile project, which has long felt as if it were more of a metaphysical mystery than an actual musical undertaking. Paradoxically, the Beach Boys seemed more artful because of what the public wasn’t hearing from them.

Some bands—the Beatles—don’t age. Others age very well (which isn’t to suggest they’re not timeless), and that’s the Beach Boys. It’s as though Beach Boys’ music needed to be in the world long enough to age properly. Consider the lo-fi, practically more-natural-than-nature vibe of 1967’s Wild Honey. This music feels both older than any woodland and as if it’s forever situated in a dream realm/glade we’re all traipsing through, without consciously noting as much.

We’re not going all-out trippy-dippy, though, for the film celebrates how competitive the Beach Boys were. Learning about the Beatles and immediately recognizing their capabilities—despite thinking “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was a nothing song—Brian Wilson remembers, “It got us off our asses,” and to the affray the Beach Boys hustled.

One band is dealt an epiphanic haymaker by the other—a fresh challenge of where it's really at—and then counters with what's akin to a body blow to the mind. Even decades later, you can detect in their voices what a challenge the Beach Boys took the Beatles’ Rubber Soul to be in terms of their need to elevate their own game, which is to say, their art.

Likewise, we hear Paul McCartney express concern whether his little English quartet could stand in with Pet Sounds. Few people think of Sgt. Pepper as a Beach Boys-related record, but it doesn’t happen without the American West Coasters. Peace and hugs? How about art and competitive fire? The Beach Boys were not solely this euphonic surf-and-motor band any more than the lads from Liverpool were merely moon-in-June songsters.

You will learn about the band’s core spirit. Their needs. Their despair. Their collective self-doubt. Money problems. How their past—and what may be the finest compilation of all-time—saved them. Their soul.

The Beach Boys, as we see in this film, wanted the journey. A lot of people don’t want the journey in life. Same with many bands who have a few hits and shoot for more of the same.

Imperative to art, though, is courage. The willingness to risk, to seek. There are some wonderful interviews with the members of the Wrecking Crew, the big-time talent studio musicians who helped Brian Wilson execute some of those musical dream visions of his. They talk about this young guy who couldn’t read music, and yet he found a way, conversationally, to get them to understand what he was hearing in his head. He wasn’t going to stand on ceremony or be denied. He was an artist who extended himself.

That’s enormous. It’s part of how you make a song like “Good Vibrations,” which needed all of two seconds to let you know that this was a sound that would be changing the world. Honestly: Have you ever heard anything that sounds like those first two seconds over the course of that gossamer-textured “I”? Do they not hit you anew, as if you’re hearing them for the first time, each time that you do?

The Beach Boys attests to how transportive and open America’s greatest harmony act was. They will take you places—if you’re willing to go. But that’s the thing about a journey, and also a journey with a collective of artists.

This is a film of received Socratic wisdom, of the knowledge that we may not know what we think we do. Don’t mistake one beach for the sum total of all beaches, the documentary tells us. There are various hot spots up and down the coast. You just have to make the trip—in life and the music of life—like the Beach Boys did.

You’ve Never Heard the Beatles Quite Like This

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.