J Balvin, Latin America’s biggest star: ‘In the super-macho-man reggaeton world, I looked weak’

Where is J Balvin? It’s the question on everyone’s lips – or rather fingertips, dozens of which are right now tapping away on phones demanding the whereabouts of Latin America’s biggest star. We were meant to meet 25 minutes ago, and the window for our interview is rapidly closing: before he takes the stage tonight, he’s got the meet-and-greet; then vocal warm-ups; then downtime. Downtime is crucial. What about after the concert? After the concert there’s a party, I’m told. Translation: no chance.

It’s a certain calibre of pop star who can pay to fly a journalist to Paris for an interview, and then vanish into the night. Balvin, whose first name is José, is of that calibre and then some. The 39-year-old is among the most listened to artists in the world. In 2018, propelled by the success of his fifth studio album Vibras, he surpassed Drake to become the most streamed artist on Spotify with 48.1 million monthly listeners. Today, he has 57 million. On YouTube, 14 of his music videos have a billion views, the largest number of any artist.

Balvin is one of a handful of musicians bringing reggaeton, a genre that mixes Spanish-language hip-hop with the rhythms of Caribbean music, out of the Latin niche and into clubs and charts around the world, like here in Paris – or in London, where he’ll play at the O2 next week.

All this to say, Balvin is a big deal – which perhaps only needs saying in the UK, where reggaeton is still a fringe genre and Balvin’s Auto-Tune croon has cracked the Top 10 just twice: first with Beyoncé’s remix of the infectious boom-pa-dum-dum beat of 2017 “Mi Gente” (you’ll know it when you hear it) and then with his Cardi B collaboration “I Like It” in 2018.

Balvin is by far the most pop starry pop star I have met. And we do eventually, meet that is – at the meet-and-greet, which takes place in a powder-pink-tiled locker room below the stadium where 20 or so fans are gathered, ranging in age from anywhere between nine and 40.

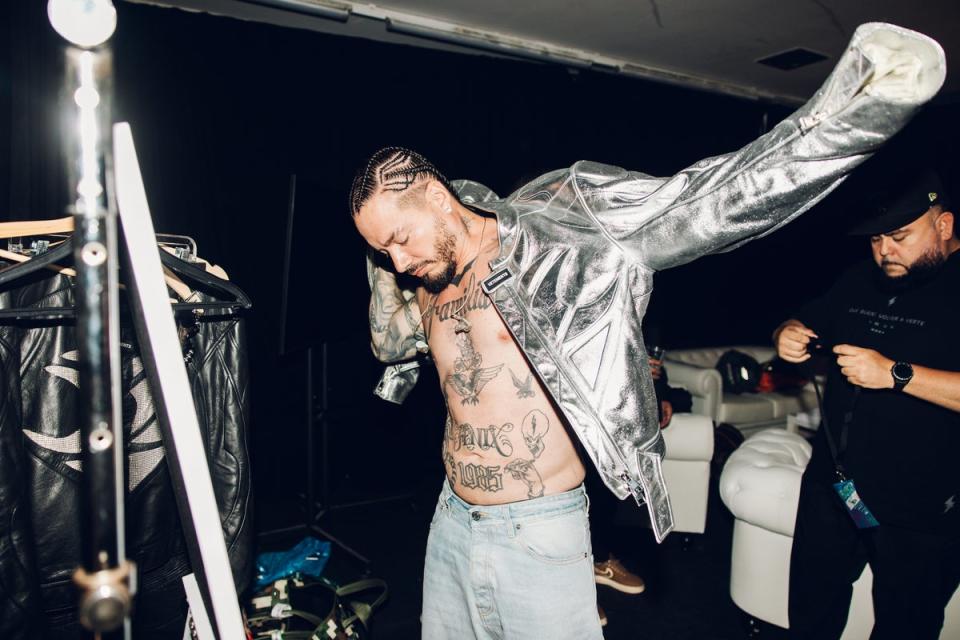

Age is just a number: every fibre of Balvin’s being seems to scream this. Tonight, he’s wearing clear glasses (the fashion kind, not for reading), a heavy leather jacket, and jeans that are ill-fitting in a cool way. The glasses stay on as he embraces fans, takes photos, and signs T-shirts and phone cases. One woman, who doesn’t speak Spanish, has flown seven hours from New York City to be here. Balvin’s songs, performed exclusively in Spanish, tend to leap over language barriers.

“Since day one, I wanted to cross over in Spanish,” Balvin tells me, after the fans have dispersed and we’ve set up on a nearby pleather sofa. He lounges; I perch. “That was always my vision. There’s guys in English making me sing words that I don’t even know what I’m saying, so why can’t we do it the other way around?” He has stuck to his guns; there is not one English song in his repertoire. “The timing was also, you know, perfect to make reggaeton global,” he adds.

It’s true that his timing has been immaculate. There has been the simultaneous rise of Latin trap artist Bad Bunny and Karol G – not to mention the extensive groundwork laid by their predecessors: Don Omar and Daddy Yankee among them. Balvin’s first streaming smash “Mi Gente” was released during the caliente summer of “Despacito”.

Balvin, then, is not unique in his success, but he is the first Latin artist to play the main stage at Coachella, headline Lollapalooza, perform on Saturday Night Live, and launch his own Jordan sneaker with Nike. (Later tonight, he will give a pair to two lucky fans he invites on stage.) No doubt, his rise has been buoyed by the several high-profile features on songs by Ariana Grande and Justin Bieber. If you were an artist in the 2010s trying to tap into the Spanish-speaking market, Balvin was your man.

More than a musician, Balvin wants to be a mogul – hence his nickname El Negocio aka The Business. A cynic might say the two songs he released with Ed Sheeran, Britain’s most bankable balladeer, last year are part of a masterplan for world domination. “There was a moment in life in the last two years that I was more focused on the game than the music itself and I got lost in it,” Balvin confesses, when I ask if the CEO side of things has ever encroached on the art. “The numbers come in and sometimes we get caught up in the business, so you forget what’s important – which is being happy and confident.”

Balvin grew up middle-class in Medellín, Colombia. The son of a businessman, he had a comfortable childhood at the tail end of Pablo Escobar’s rule – immortalised, and arguably glorified in Netflix’s smash hit Narcos. Balvin was eight when Escobar died, but the drug lord cast a long and violent shadow. To this day, he refuses to say Escobar’s name. “Never,” he scoffs. “I don’t care about him. He’s nothing. His son is one of my best friends, but he agrees with me.” Balvin doesn’t care for the way Escobar has been glorified on screens around the world. “There’s nothing to feel proud about. But it’s our history. We can’t rewrite our history.”

When he was 17, Balvin signed up for an exchange programme that would take him to America. Bright lights, billboards, skyscrapers: he couldn’t wait. Then he landed in Oklahoma. Balvin laughs at the shock of it now. “I thought it was going to be a city like New York and then I landed in the middle of a forest full of wolves, foxes, bears and snakes,” he says. “You know how people picture Colombia as a jungle? That’s basically where I went to live.”

Colombia is not a racist place. We see Black people, white people, whatever… but once I landed in Oklahoma, I felt what it was like to be rejected

Scarier than the wolves, though, was the racism he encountered. “Colombia is not a racist place,” he says. “We see Black people, white people, whatever… we don’t see a difference, but once I landed there, I felt what it was like to be rejected. It was a super white place where a Latino or a Black American wasn’t welcome, even the indigenous Americans weren’t welcome.” It was tough, he says, to realise “there was this divide in the world”.

Balvin recalls how his class at school in Oklahoma had been told the US won the Vietnam war. He raised his hand and called the teacher a liar. “I was expelled,” he says. “There are places where they still control a lot of the information because they want to keep people in a cage.”

Although his name is now synonymous with the genre, reggaeton wasn’t his first love. As a kid he was more into indie rock – on his knee is a faded Nirvana tattoo – but he changed his tune after hearing a friend’s bootleg CD of Daddy Yankee at a gas station. The artist’s 2005 record Barrio Fino, featuring the certified banger “Gasolina”, went on to become the best-selling Latin album of the decade. If Balvin is the Prince of Reggaeton, Daddy Yankee is the King. “I will never forget that because he was the one who pulled me in,” Balvin says. “I’m always grateful for him.”

His entry to the genre was not frictionless. Balvin was late to the game, and coming from a middle-class background, he didn’t fit the mould of a reggaeton rapper, not least because he was Colombian. Some have said that Balvin is guilty of appropriating and whitewashing the genre, which hails from Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and Panama.

Today, he demurs, focusing instead on the positives of his outsider status. “The fact that I was Colombian, it also makes me shine more because I wasn’t compared to Puerto Ricans,” says Balvin, though he concedes that it was “a hard task” in getting people to broaden their perception of reggaeton to include countries beyond Puerto Rico. “When I started gaining the respect from the music industry and from Puerto Rico and started collaborating with them, the public in general really embraced me,” he says.

Balvin certainly has passionate opinions. He is very vocal, for instance about wanting to change the world’s perceptions of Latinos. “We can be whatever we want, we don’t just work in construction,” he says. “I’ve nothing against that, but don’t put us in a box.” All the same, he stays out of politics. “I do not like politics,” he reiterates. If he liked it, he’d be a politician. “But I’m not ready for that, so that’s why I’m an artist.”

“I’m a humanitarian,” he offers. “I’m for humans. That’s the way I’ve always felt.” He is keen to give back. “I’m doing what I can with my foundation to help different foundations – sports, music, cancer. I want to touch a lot of different ways that we can help. Never leave that [sort of thing] to the government. No, thank you.”

As with any artist on the rise, there have been moments of controversy. In 2021, Balvin was awarded Afro-Latino Artist of the Year at the African Entertainment Awards USA. A backlash swiftly followed given that Balvin is white Latino. “There had been a misinterpretation of what the guy [in charge of the awards] wanted to do,” he says. “They weren’t saying straight-up Afro-Latino. They were basically saying, ‘the Latino who supports Afrobeat music’, and of course they put Afro-Latino and I’m not Afro-Latino.”

It feels like a crystal generation, really fragile. Sometimes they don’t even know what they’re complaining about

It was a dark time, he adds. “Every move I made would get a backlash,” he says. “I never had that in my life until three years ago, so it was really tough for me to understand. Sometimes people don’t want you to win, sometimes people don’t like you for no reason. It feels like a crystal generation, really fragile. Sometimes they don’t even know what they’re complaining about.” As in, they’re sensitive? “Yes, and they don’t even know what they’re sensitive for.”

Other times, he understands why people are angry. Months before the awards saga, Balvin removed the music video for “Perra” (his collaboration with Dominican rapper Tokischa) from YouTube after fans had called it racist and misogynistic. The video, which was directed by Tokischa’s manager, featured Black models wearing facial prosthetics to resemble dogs. Balvin was depicted walking the women on leashes. Balvin apologised quickly and profusely. “Absolutely, yes,” he says today. “There’s no excuse and what’s done is done.”

He chalks that instance up to his own naivety. “I wanted to support the Afro-Latina girl who had the vision for the video, but I did not consider the world out there.” By that he means the wider context into which the video was being released. “I’ve learnt from that mistake,” he says. Now when Balvin is going to make a music video, he ensures he knows the concept inside and out. “Still, it’s kind of sad sometimes because if you want to express something – some people don’t understand that you’re creating your own world or telling a story.” Freedom of expression is his point.

Balvin has had his own run-in with mental health – dating back to that “dark time” of backlash after backlash. “I never thought I was going to suffer from mental health issues,” he says. It took him a while to get to grips on this new reality: “This chemical imbalance I wouldn’t wish on anyone.” He took a break from social media but admits that since he returned, he has once again become an addict. He looks up and clocks the concerned face of one of his team seemingly worried he’s let something slip inadvertently. “Hey! I’m just talking about social media. I’m an addict on social media,” he laughs, shaking his head.

It wasn’t easy to speak up about his depression, but it was the only way he knew how to cope. “Of course, in the super macho man reggaeton world, I looked like the weakest one. But I think it takes balls to acknowledge it and be fragile and human,” he says. “Those sorts of things are not negotiable with me. I’m not going to put the business first; I come first.” In 2022, he launched OYE, a mental health app available in both Spanish and English.

The worst of it is hopefully behind him – something for which he has his son, Rio, to thank. He and his partner, the Argentine actor and model Valentina Ferrer, welcomed their first child in 2021. “Since my son was born, I haven’t had any problems,” he says. “I found the light and the reasons to keep elevating my dream and not give up. And now we’re here.” He would, though, like to cry some more. It’s therapeutic, he’s heard. Balvin hasn’t cried in five years. “I’ve tried but it won’t come,” he says. “When it does, I hope it’s tears of happiness. I want to be swimming in it.”

J Balvin performs at the O2 on 5 June 2024; tickets available here.