Jeffrey Wright on Bond, bankability and his Oscar nomination: ‘I’m thinking about it more than is healthy’

For the first time in his career, Jeffrey Wright is up for a Best Actor Oscar. I meet the star of the slippery new satire American Fiction before any announcements have been made. Still, Wright, dressed all in black in a slick London hotel, is aware of the awards buzz. “Yes”, he concedes demurely, “it’s swirling around.”

Wright is known in the industry as “Mr Dependable” – a multi-layered character actor who excels in sharp indies and classy blockbusters, including three Bonds, three Hunger Games, and one Batman. He’s proud of that work. For so many reasons, though, it’s not what he wants to discuss today. In fact, when I raise the issue of the next Bond movie, and who he’d like to see stepping into Daniel Craig’s shoes, the 58-year-old all but shudders. “I’ve no idea,” he says, loftily. “I have no opinion.”

To be fair, Wright’s character – 007’s CIA pal Felix Leiter – did get offed in 2021’s No Time to Die. But surely he’s intrigued about where the brand will go? Wright, noticing the sugar on the table and eagerly pouring a sachet into his coffee, tries to summon some enthusiasm. “Culturally, it’s important,” he says. “I suppose it is, yes.”

Wright gets that people want to hear about Bond. A bit of him is willing to play the game. A bit of him is frustrated. And he lives with those contradictions. His character in American Fiction is similarly conflicted. Knotty, nuanced and tender, the film – which has been nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay – explores issues connected to race, class and gender, without labouring a single point.

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Wright), a hifalutin professor/author, is sick of being told his books aren’t “Black” enough. Adopting the pen name Stagg R Leigh, he bashes out an intentionally crass novel about “the hood”, hoping to expose the covert racism of an industry that rewards Black authors for serving up ghetto clichés. But when white publishers pronounce the book an “authentic masterpiece”, Monk doesn’t say gotcha. That’s because, though he grew up in a house with a live-in maid, Monk isn’t rolling in cash. In fact, newly responsible for his increasingly fragile mum (Leslie Uggams), poor old Monk needs the money. The disgruntled academic, forced to adopt the persona of macho fugitive Leigh, finds himself being courted by a Tarantino-esque director. Will Hollywood, or Monk, get the last laugh?

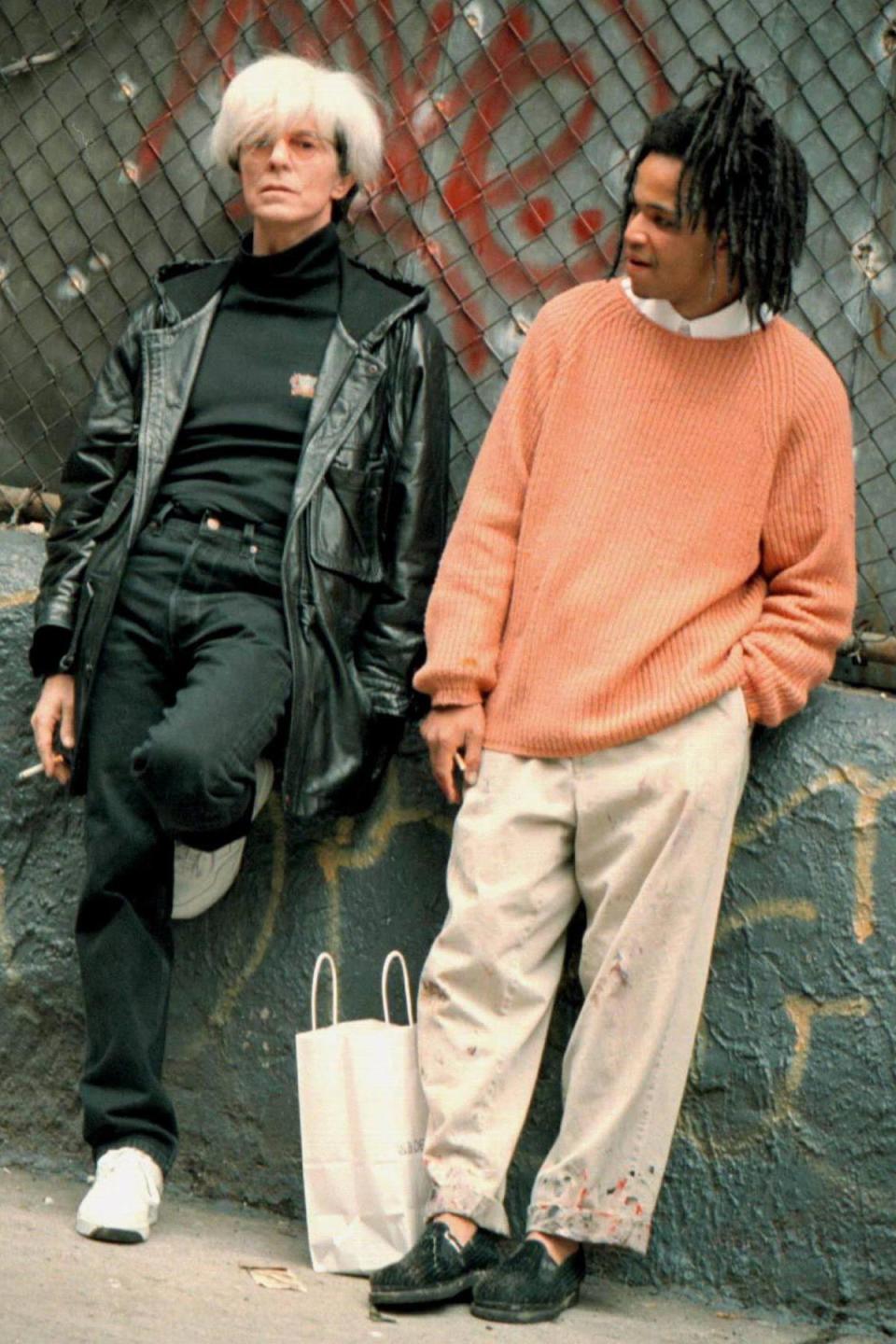

That Wright is brilliant in American Fiction goes without saying. He’s not capable of being anything else. Think back to his breakout role in the Julian Schnabel art world biopic, Basquiat (1996), in which he played Jean-Michel Basquiat, a genius constantly patronised or insulted by supposedly civilised folk (the Haitian-American artist is told he’s “the picaninny of the art world”). At one point, the beautiful and drug-fuelled twentysomething hallucinates a bold art installation in which white paint is sploshed on black tyres. The character gazes at his work-to-be with an expression that’s befuddled, broken and ecstatic. You want a moving image? Wright’s face says it all.

There was never any perception that that story – my work – had some great future potential. No support was provided by the quote, unquote, powers-that-be

He’s equally astonishing in the two films he’s made with Wes Anderson. As a radiantly poetic restaurant critic in The French Dispatch (2021), Wright spins tragi-comic gold out of whimsy, while as the manly General Gibson in last year’s Asteroid City, he somehow makes the word “poodle” worthy of a guffaw. Wright’s voice, by the way, is one of his most powerful weapons. Especially when talking fast, he can sound like a little kid. When adopting a more leisurely pace, he has the melodious authority of Orson Welles.

Famously well read, Wright tells me he’s always admired The Independent’s Robert Fisk (“The absolute best correspondant writing on the Iraq war, I found”). He also knows a lot about Arsenal FC. “It’s November 2003. I’m in The Elgin Crescent pub, Ladbroke Grove. I’m looking up at the telly. I see Henry, Cole, Campbell, Lauren: these super dynamic brothers on the field. I’m like ‘Those are my boys!’”.

On top of all that, the guy is trendy. I’ve been told, by one of the film PRs, that Wright’s fashion choices are impeccable. One of them says, “Check out the high cut of his trousers! When it comes to Jeffrey, we’re thankful for an ankle!” (During the interview, I take a sneaky peak at his trousers. They really are top-notch).

That Wright is a respected and popular figure is undeniable. That said, American Fiction hones in on the toxic drive for profit that underpins both the publishing industry and Hollywood. I want to know if the film’s first-time director, Cord Jefferson, came under pressure to choose a more “bankable” leading man. Wright, stirring his coffee, grimaces. He says: “Who else do you think could play it? Who, in your mind, is, quote, unquote, more bankable?”

I say I’m not equating bankability with talent, just guessing that some of the studio chiefs might have preferred a more tried and tested leading man. Wright, by now stirring his coffee at a ferocious rate, frowns. “What differentiates our film from many other films is Alana Mayo, the head of Orion Studios,” he says. “She’s a Black woman. Her perception of what’s bankable is different to other people’s. To her mind, I am bankable. To Cord’s mind, I am bankable. I do my work in my way and that’s what Cord wanted. He wanted my work.” Wright leans forward across the table and I realise he’s shaking. He says, fiercely, “No one does work like me.”

He sips his coffee and the next time he speaks his voice is quieter. “I have never in my career been invested in by the industry. Never. When I did my first lead in a film, as Jean-Michel Basquiat, it was pretty good. That film was never supported by the studio [Miramax]. It was pulled out of the theatres while it was doing well. I don’t know why. There was never any perception that that story – my work – had some great future potential. No support was provided by the quote, unquote, powers-that-be.”

Back then, he didn’t consider how this would affect his earning power. “Early on,” he says serenely, “I had a disdain for making money. In my self-righteous way, with the self-righteousness of youth, I thought it was impure. I never wanted to work in sitcoms. I didn’t want to ‘create the brand’. I didn’t want to placate the market.” He rolls his eyes. “That changed when I had kids”. Wright, who was born and raised in Washington DC, now lives in Brooklyn, in a house he shares with his two grown-up children from a marriage to the British actor Carmen Ejogo (the couple divorced in 2014).

Wright can see many overlaps between himself and Monk. In both the film and Erasure, the nimble novel American Fiction is based on, it’s made clear that Monk’s dead father was upper middle class, unlike Monk’s mother, who was “well-educated, but from a more working-class background”. Wright says, “That’s my family! On my mother’s side, I come from very salt-of-the-earth people, down in Virginia.”

He tells me a story about one of his extraordinary relatives. As a young woman, Wright’s great-great-aunt moved to Brooklyn, where she found work as a maid (“She kept house for a Jewish family”). Once there, she hatched a plan. “She didn’t want the girls – my mother and aunt – attending segregated schools in the South. She told my grandfather to send the children to her.” Wright’s grandfather (who’d been working since the age of 14, when his own father died of influenza) agreed. “So my mum came to Brooklyn for middle school and my aunt went to a girls’ high school in Bedford-Stuyvesant. That made all the difference. It changed the trajectory of our family.”

Wright’s father came from a long line of New York professionals. But he died when Wright was a baby. When I ask how his dad died, Wright’s eyes flit from side to side, like frantic fish. He slips his hand into his jacket and discreetly starts to vape. He would much rather talk about his mother, Barbara Evon Whiting-Wright, who, after college and grad school, worked as a lawyer for the government and brought him up with the help of the aforementioned aunt.

Beaming, Wright says, “I was an only child, so there was a lot of focus on me. My mum had high expectations. As a teenager, I was an athlete. I played American football and lacrosse. I was a goalie in lacrosse and my mum would come to my games. I could have a stellar game. I could have made 20 saves and only let one goal in and she might ask me, ‘What happened? Why did you let that one in?’” She was always that way. “I was in elementary school. There was a grade I was given. ‘Very good’. That was the highest you could get. But she didn’t know that. She said, ‘Why didn’t you get excellent?’”

Wright is laughing so much he’s almost wheezing. “That was my mum. At the same time, no one – when I needed help the most, whether as a kid or an adult – was more reliable and there for me than her. At the worst times in my life, she was my rock and saviour.”

Just like Monk, Wright took care of his mother when she became ill. Wright clears his throat and explains that his mother died about a year before he got the script for American Fiction. “She had colon cancer. So it was rough. But when she passed – and it happened pretty quickly, quicker than we’d hoped – it was gratifying how much trust she had in me. A friend of mine said, ‘Her investment paid off!’”

Wright says he’s optimistic audiences will flock to American Fiction. “We all have mess in our families. Odd corners; beautiful ones. Monk’s family, for that reason, is extremely easy to relate to. We make room within the film for people to find something to connect to, in a way that I think is seriously surprising to those whose perceptions of bankability you were curious about.” Since being released in the US, American Fiction has done slow but steady business (made for roughly $10m, it’s earnt $11.8m so far). With the Oscar nominations now in, its box office is expected to soar.

I’m intrigued to know what Wright makes of the Academy Awards. Back in 2016, he lent his voice to the cult Netflix animated series BoJack Horseman, playing a freakishly supple hamster and ex-film producer by the name of Cuddlywhiskers. The character had strong views on the subject, reminiscing about the day he won an Oscar: “I thought, ‘This is supposed to be the happiest day of my life, but I’ve never felt more miserable. Oscars are meaningless!”

Wright chuckles. “Hey, if they’re handing them out, I’ll take one. Or two. I’ll take several!” He’s thought about what he’ll say if he wins, and has practised the odd speech in his head. He pulls a face. “Anyone who does this work who says they’ve never considered that is absolutely lying to you. I’ve thought about it, sure. I’m thinking about it more than is healthy!”

In American Fiction, awards ceremonies are a bad joke: carnivals of excess designed to con outsiders into thinking an industry is meritocratic. In the real world, well, let’s see what happens on 10 March. But here’s a prediction: if Jeffrey Wright triumphs, he’ll use his acceptance speech to thank Barbara Evon Whiting-Wright, who always knew her son was priceless.

‘American Fiction’ is in cinemas