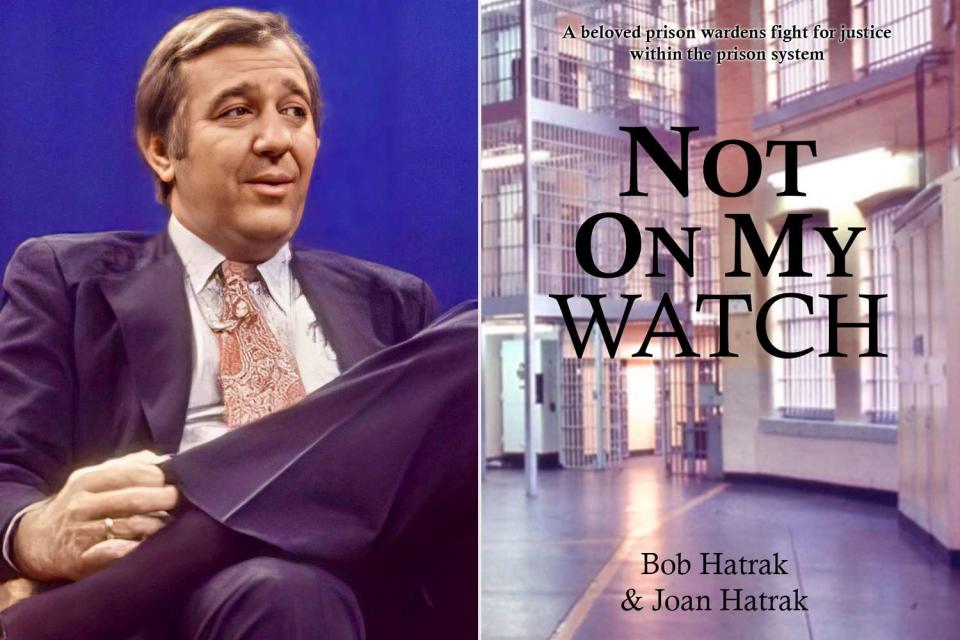

Man Behind 'Scared Straight' Reflects on Prison Program Nearly 50 Years Later (Exclusive)

In his new book, Bob Hatrak reflects on his time serving as the country's youngest warden of a maximum-security prison

Courtesy of Hatrak Family; Villa Magna Publishing

Bob Hatrak; Not on My Watch coverThe juvenile awareness program "Scared Straight," which went on to have a life of its own on camera, has a direct connection to former prison warden Bob Hatrak.

Known for the impact he had in the 1970s at New Jersey's notorious Rahway State Prison (now known as East Jersey State Prison), Hatrak, now 86, looks back at the roots of the initiative in his new book, Not on My Watch.

“When I started working at Rahway prison, it was in the early ‘70s, and all of the experts at the time were saying that rehabilitation is past tense and that what needs to happen is keys need to be thrown away, and we needed to build more prisons and lock more people up,” Hatrak tells PEOPLE in an exclusive interview. “Well, that's when my staff and I took over. We had to swim against that tide."

Hatrak says he got the idea for the seminal program from Rick Rowe, who was incarcerated at the time. According to a 1979 story in The New York Times, Rowe was serving a life sentence for rape and an assault.

“It was a rainy February evening,” Hatrak recalls, sharing that Rowe was "in tears" at the prospect of his own son ending up at Rahway prison one day "unless I could help him out," which Hatrak did.

Hatrak continues, “He said, ‘Well, can you allow my son to be on a tour, and find out what prison life is all about?' "

And so, the idea to have "lifers" talk to young people in an attempt to “scare” them away from ending up in prison was born.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

“The kids came in and it wasn't scripted,” Hatrak tells PEOPLE, noting that he never offered any guidance on what to say.

"They knew prison life better than I did from the inside, and that it would be more important for them to share their experiences," he explains.

After the inaugural encounter was held on Sept. 6, 1976, the program ended up being featured in an Academy Award-winning documentary narrated by Peter Falk.

"One day, I got a call from [film director] Arnold Shapiro who had read a story in the Reader's Digest magazine...about what we were doing, and he wanted to come to talk about making a film documentary," he says.

"I thought that too much publicity could possibly hurt, so I wasn't looking for a documentary. But he talked me into letting him come in and we talked about what he wanted to do," he adds. "I told him, ‘Well, if it's okay with the lifers, it'll be okay with me.’ And he talked to the lifers and they really wanted to do it. So I said, ‘Okay, let's go ahead.’ “

Hatrak tells PEOPLE that the day after the film aired on television there was a “quiet calm” in the prison.

Speaking of his own recollection of the response to the documentary, he says that "men who were shunned and feared by society now felt a sense of self-respect and believed that they now had an opportunity to give back to their own communities."

Hatrak adds that after the program began disciplinary charges began to decline and that there was a better relationship between correction officers and the individuals who were incarcerated.

The documentary went on to inspire a number of television specials as well as the long-running series Beyond Scared Straight!

Related: Man Who Earned College Degree While Incarcerated Gets Accepted to Law School Months After Release

When Hatrak landed at Rahway, he was the youngest warden of a maximum-security prison in the country.

At the time, he was pursuing a career as a basketball coach at Fairleigh Dickinson University in nearby Teaneck when a job opened at the prison, and he soon came to realize the impact he could have on a different group of young men.

Through his job at the prison, Hatrak's insight and compassion were the driving force behind various vocational training programs, as well as The Escorts, an American R&B group formed at the prison in 1970, and the boxer James Scott, who became the second-highest ranked contender in the World Boxing Association’s light heavyweight division while he was incarcerated for murder at Rahway.

Villa Magna Publishing

Not on My Watch coverWhen he first sat down to document his life with his wife Joan, they had a very small audience in mind.

“We wanted to write something for our children so that they would know about us when we were gone,” he says. “And we started to do that, and after a short while, we determined that there was a lot more to the story than a little pamphlet for the children.”

“So we started to write and still didn't think about a book," he adds. "But again, after a short time, it turned into a memoir because it was getting so huge."

Today, Hatrak says there's not much he would change about "Scared Straight," even as some studies of the program have called into question its overall efficacy outside the prison's walls — criticisms which the former warden "absolutely" disagrees with.

“Basically, it was their conclusion that programs such as Scared Straight helped to increase criminal behavior by juveniles and not decrease it," he says. "My problem with those studies is that they followed a small number of juveniles for only a short amount of time."

"There was a follow up to the first documentary; “Scared Straight: 20 years Later” that did follow up with the juveniles in the film. I believe that 10 out of 12 participants in the original documentary completed school, got jobs and did not engage in criminal activity," he adds.

Although he acknowledges that "not all social service officials have positive comments about the Juvenile Awareness Program," he feels like "long term studies need to continue."

As he looks back on the legacy of the program, Hatrak feels proud. "It is a good thing that we did at Rahway," he says. "And I think we would do it again."

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.