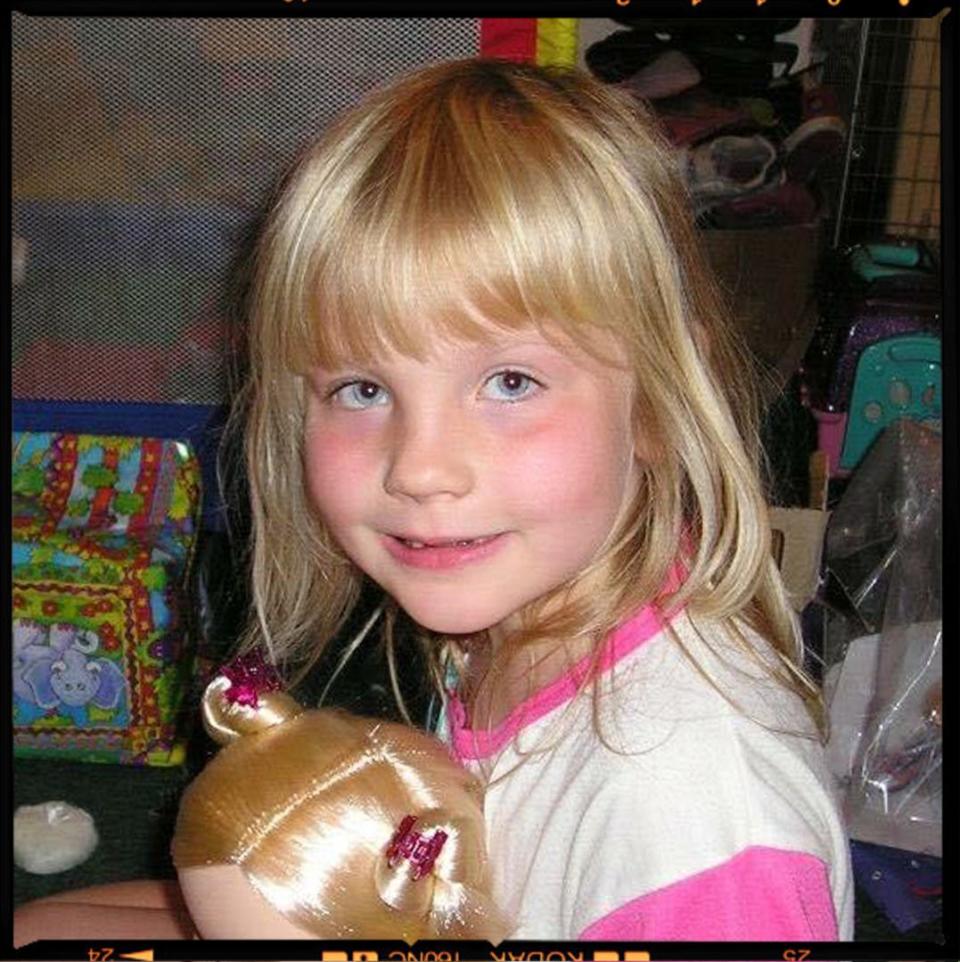

"Like many women, my ADHD went undiagnosed for 24 years: here's what I'd tell my 12-year-old self"

It’s 2008, parents evening. I’m ushering my mum away from my French teacher because I know I’ll get an earful. It’s been the same story: “She’s very clever, and has so much potential, if only she just stopped talking, concentrated and gave up the class clown act.” French was particularly bad. I’d make my own entertainment by winding up the class. I was sent out to count the bricks in the hallway and write lines almost every lesson.The only thing I was interested in doing when I was older was being in front of the camera or working for a magazine. I wasn’t interested in French, so I didn’t try.

It was the same deal outside of school. Anyone who visited my parents – hell, even the postman– I’d butt into their conversation to perform a dance routine. I was musical and my mum (bless her) got me some singing lessons at a local lady’s house. As soon as mum left? I went and hid in this poor woman’s wardrobe. I’d avoid the actual task at hand like the plague, with zero clue it was actually a disability.

There was a kid in my primary school class (of only 7 pupils, so I remember it clearly) who had an ADHD diagnosis. He was often just referred to as a naughty kid, but he had a reason for it. We were often getting in trouble together, but nobody thought to question my symptoms.

When my mum took me to a child psychologist, he simply told her I was ‘mollycoddled’. I had undergone major surgery for my physical disabilities as a young child, which according to him had made me an attention seeker.

I first came across the word ‘neurodiversity’ at university. Coincidentally, I was put in halls with two friends, Annie* and Ziggy*, who also had ADHD (although none of us realised until later on). They both presented in different ways – Annie was more introverted, but struggled to concentrate, and Ziggy presented ADHD in a more widely understood way, always going 100mph. We connected on a deeper level: Annie and I through the only way we could revise for exams (the night before), and Ziggy with an endless supply of energy that dispersed in all-night cartoon binges.

But it was after graduation that things truly clicked for my understanding of my own ADHD. Another friend began candidly sharing her ADHD journey, and how she had been misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder. She shared helpful infographics and ADHD memes I found relatable. We swapped lengthy voicenotes. She encouraged me to seek a diagnosis, so in 2020 at the age of 24, I finally did. I was referred to a specialist by my GP, and nine months later I was officially told that I have combined type ADHD. I felt relief. I felt validated.

I scored high on the symptoms checklist – a short attention span (especially for non-preferred tasks… like French), habit of losing things, extreme impatience and continually starting new tasks without finishing previous ones. Some uneducated folk may perceive ADHD symptoms as laziness, but I’ve always worked hard, holding down three part-time jobs all at the same time at university as well as extracurriculars. The inability to get started on tasks – no matter how important, easy, or pleasurable they were – was debilitating. Even if I busting for a wee, I would put it off. This comes under the umbrella term linked with ADHD known as executive dysfunction, sometimes referred to interchangeably as mental paralysis.

The signs were all there – how was it missed? I wonder daily if I was a man displaying these traits, would they have been picked up far sooner?

The ADHD Foundation shares that boys are diagnosed and supported three times as much as girls. Out of 14.6 million UK children under 18 years, it is estimated that 423,000 girls in the UK under age 18 have ADHD but are three times less likely than boys to be diagnosed and supported.

When it comes to being diagnosed in adulthood, it says that as many adult women are diagnosed as men, “which suggests girls and young women are neglected by health services and in adulthood misdiagnosed and incorrectly treated for other conditions.”

There are varying reasons as to why symptoms go unnoticed in girls, says Leanne Maskell, an ADHD Coach, director of ADHD Works and author of ADHD: an A to . “The traditional stereotype of ADHD relates to a ‘naughty school boy’ disrupting the class, rather than the quiet girl who can't listen, disrupting only herself and struggling in silence.” Some reports suggest girls experience more inattentive symptoms (though this isn’t always the case), meaning they may be less disruptive.

Girls may grow up internalising their suffering and “masking” their symptoms, Maskell adds – and women may camouflage what they’re experiencing, instead forcing themselves to act in a ‘socially acceptable’ way.

It’s blatantly obvious to me looking back that I was struggling. I was regularly punished by teachers, thrown into detention and out of lessons.

In my experience, women can be better at masking our symptoms. It’s something I only got ‘better’ at throughout my teens and into my twenties.I’ve had to work very hard on unlearning that.

Now, I’m learning to embrace my quirks and to not mask them, instead asking for accommodations to be made if needed and tackling life head-on. A big one for me is now allowing myself to fidget – or stim, as it’s often referred to in the ND community – if I need to. This might look like jiggling my knee or another form of intense, repetitive movement to keep my brain stimulated. I’ll never forget one teacher yelling at me to stop tapping my fingers because it “drove him insane”. Growing up, this and other similar instances only reaffirmed the idea that I was annoying and caused me to suppress a lot of things which made me comfortable and that felt natural to me. Now I’ll outwardly tell anyone I’m around: “sorry, I’m doing this because I have ADHD. I can’t help it.”

I’ve almost been forced to find a new way of tackling things. The more I educate myself and connect with similar neurodivergent people, the more I realise how much I actually need support.

I wish I could say everything got better once I started stating my disability to employers, but unfortunately, I’ve experienced a string of prejudices. I’ve found that working as a journalist, not all (but too many) editors don’t understand or make allowances for a writer like me who can’t concentrate and get an article written in time because they’re made to be in a loud, busy newsroom when I’d be more efficient working remotely. I can’t change that they think giving me hand-written instructions because I cannot retain verbal ones is “hand holding”. What I can change is not letting unconscious ableism affect me

Medication has significantly helped me. Since taking Elvanse I finally understand what it’s like too not feel blocked, to have some control over my decisions and to have regulated motivation, not to bounce from extreme moods to numbness, often being unable to function. It’s not the case for everyone, and the national shortage of meds, means it’s something I’ve had to cope without.

After years of settling for less, I've also met a partner who makes me feel more seen, loved and understood than anyone else ever has – something every neurodivergent person deserves. My boyfriend Blake is there through every meltdown, manic hyperfocus, sensory overload, every small business I’ve started and got bored of a month in… and has never once made me feel less than because of those things.

For me, finally getting a diagnosis was about validation, and healing my inner child. That kid who was used to being yelled at and kicked out of classes feels seen. Legitimising my quirks, what’s me – and that I’m certainly not alone – has changed everything. I wish I could tell my 12-year-old self that.

*Names have been changed

Follow Mared on Instagram, TikTok and X. You can also watch her documentary about struggling to be diagnosed with ADHD.

What is ADHD?

ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, is “a neurodevelopmental condition that can lead to difficulties with inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity,” explains the ADHD Foundation.

To be clear, “ADHD does not affect your level of intelligence in any way”. However, the condition can make it more difficult to manage certain aspects of your life; you may struggle to regulate your emotions, for instance, or struggle to complete certain tasks effectively.

“In the brain of someone with ADHD, the neural pathways are not developed in the same way and this impacts your ability to concentrate, and focus more than for neurotypical people,” the charity continues.

How is ADHD diagnosed?

A GP referral will be made to a specialist. ADHD is diagnosed differently in children and adults. For a child to be diagnosed with ADHD, they must have “6 or more symptoms of inattentiveness, or 6 or more symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsiveness”, according to the NHS website. “Diagnosing ADHD in adults is more difficult because there's some disagreement about whether the list of symptoms used to diagnose children and teenagers also applies to adults,” it continues. Only a qualified professional can diagnose ADHD.

What are the signs of ADHD in women?

As per the NHS, symptoms of ADHD in adults may include:

Carelessness and lack of attention to detail

Continually starting new tasks before finishing old ones

Poor organisational skills

Inability to focus or prioritise

Continually losing or misplacing things

Forgetfulness

Restlessness and edginess

Difficulty keeping quiet, and speaking out of turn

Blurting out responses and often interrupting others

Mood swings, irritability and a quick temper

Inability to deal with stress

Extreme impatience

Taking risks in activities, often with little or no regard for personal safety or the safety of others – for example, driving dangerously

Professor Amanda Kirby, chairperson of the ADHD Foundation, has also compiled a (non-exhaustive) list of signs associated specifically with ADHD in women.

These include:

Not completing tasks and then feeling guilty about it

Working harder than needed because you’re not sure how hard you need to work

Being over engaged and then not

Losing your day after drifting down a rabbit hole related to a topic of interest

Being distracted by the conversations of people around you

Drifting off when someone is talking to you - but being fully-engaged when the topic is of high interest

Impulsive decision making

Not being able to sit still

Sleep disturbance

Losing possessions even though you’re sure you left them in a particular place

Poorer concept of time passing

Thinking you are less capable than you are and struggling with people’s perceptions of you

Doing the things you like and avoiding the tedious things as much as possible

Of course, many of these signs may be associated with other conditions, as Dr Kirby recognises and it’s worth remembering that ADHD can appear differently in every individual. Maskell adds that, “Due to societal conditioning, women may experience these symptoms differently to men, such as with low self-esteem, rumination, burnout and comorbid health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

"They are also more likely to develop coping strategies to mask their symptoms, such as with perfectionism, over-achievement, or people-pleasing behaviours."

She also notes that hormones can have an impact. "Symptoms can change significantly in relation to menstruation or menopause, for example."

What support is there for women with ADHD?

Maskell recommends asking your GP about the support available to you. Medicine, therapy, or a combination of both may be used to treat ADHD by the NHS – although, ongoing medicine shortages are currently complicating matters.

You may also wish to work with an ADHD Coach, like Maskell, who can help you to better understand your ADHD.

Regardless of the path you choose, know that help is available. “Navigating ADHD can feel very overwhelming and lonely, so it's important to ensure you have a strong support network of family, friends, and professionals such as therapists. You are not alone, and there's no 'fix' for ADHD, because you're not broken!” concludes Maskell.

You Might Also Like