Musk Is Engaging With Europe’s Far Right But Voters Aren’t So Sure

(Bloomberg) -- Europe’s far-right parties are enjoying a high profile, including social-media engagement with Elon Musk. But the controversies have come with a cost in the polls, as they struggle to maintain momentum going into June’s European elections.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Microsoft’s Xbox Is Planning More Cuts After Studio Closings

Americans Are Racking Up ‘Phantom Debt’ That Wall Street Can’t Track

Stormy Daniels Will Return to Court in Test of Trump’s Demeanor

Musk has made no secret of his interest in the far-right Alternative for Germany. After a series of self-inflicted set-backs, it’s less clear that the party can retain the enthusiasm of its voters.

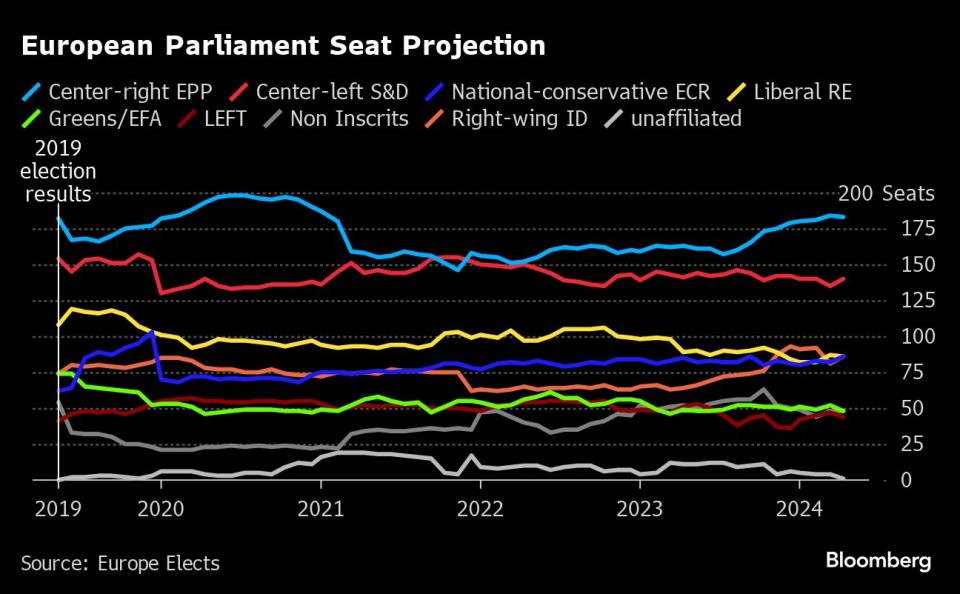

The pan-European Identity and Democracy alliance, which includes the AfD as well as France’s Marine Le Pen and the Netherlands’ Geert Wilders among its members, is projected to win 11.2% of the vote, according to a polling average compiled by Europe Elects. That would give the euroskeptic ID bloc 84 seats in the assembly, down from December when it appeared on track to win 93.

While that’s well up from the 59 seats it won at the last EU vote in 2019, those projections come on the back of several controversies that have lately hurt the AfD’s popularity.

The party’s co-leader Alice Weidel invited Musk to her office after the Tesla co-founder criticized an extremist Muslim group that held a demonstration in Hamburg. “Surely demanding overthrow of the government in Germany is illegal,” Musk had written on the platform X, which he owns.

“Dear Elon Musk, this event is just one out of many disturbing developments in Germany,” Weidel wrote back. “Please feel invited to my office in the German Bundestag at your earliest convenience to discuss in further detail.”

The timing of last month’s exchange was awkward, given that just a day later a former AfD lawmaker was among those implicated in the trial of a right-wing extremist group which was itself accused of plotting to overthrow the government by force.

Read More: QuickTake on Why German Far-Right AfD Party Has Run Into Trouble

Compared to the previous month, Wilders’ Freedom Party also suffered a slight dent in April’s Ipsos I&O EU election polling — down to 22% from 25%. In a country where the overwhelming majority of citizens support EU membership, he’s struggled to turn his victory in November’s general election into a governing coalition. Yet by tacking to the center and softening his opposition to the EU, the Dutch lawmaker may have turned off some of the hard-line vote.

Far-right groups had hoped to be able to form a blocking minority after next month’s European elections in order to water down ambitious climate regulations and propose tougher measures on immigration.

The largest political group in the EU parliament — the center-right European People’s Party — is polling at 23%, a share that would grant it 183 seats. The center-left S&D is projected to win 140 seats, while centrist-liberal group Renew is projected to get 86. That would comfortably give the three parties an absolute majority in the chamber, allowing them to block proposals from the far right.

All the same, another far-right grouping, the European Conservatives and Reformists, is vying with the liberals to form the third-largest group and is also projected to win 86 seats. The ECR, which includes Italian Premier Giorgia Meloni as its leading figure, has better relations with the center-right and could potentially push the majority to pass tougher measures on immigration or slow efforts to fight climate change.

Read More: Politicians Sense Opportunity in Railing Against Climate Action

Historically, centrist parties have refused to cooperate with these nationalist parties, effectively relegating them to the opposition. But the rise of the right has changed that calculus, and the cordon sanitaire has frayed.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, a member of the EPP, has signaled she could be prepared to work with some in the ECR after the election. “It depends very much on the composition of the parliament and who is in what group,” she said at a debate in Maastricht last month.

The AfD was forced to begin its campaign for June’s election without its lead candidate Maximilian Krah, who faces allegations of links to Chinese intelligence and a pro-Russian media organization.

The party’s number-two candidate, lawmaker Petr Bystron, can’t step into the breach: he is accused of taking money from a pro-Russia media outlet. “We will concentrate on political topics, rather than on people,” said party spokesman Daniel Tapp.

After feeding off dissatisfaction with the Social Democrat-led ruling coalition, the AfD spent 2023 rising steadily in polls of voter intention. Its decline began soon after a media report exposed that party members — among them one of Weidel’s assistants — attended a meeting where plans were discussed for the mass deportation of asylum seekers, foreigners with the right to reside in Germany and German citizens who haven’t “assimilated.”

Many Germans were reminded of their country’s Nazi past and took to the streets in their thousands to protest. In a speech to a congress of her Christian Democratic Union party in Berlin on Wednesday, von der Leyen had scathing words for the AfD. “Whether they have taken bribes from the Kremlin or not, their behavior is destructive, mendacious and in denial of history,” she said.

Beyond its scandals, the right is also struggling with the fact that individual parties don’t always see eye to eye — especially when it comes to Russia and Ukraine.

Far-right parties including the AfD, Le Pen’s National Rally and Wilders’ Freedom Party have traditionally been friendly toward Russia and are now wrestling with how to reconcile that with broad opposition to the war among voters. The National Rally’s financial ties to Russia have been under scrutiny after it took out a loan from a Russian bank, which it says it has since repaid.

Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, by contrast, have stuck to the mainstream EU line of supporting Ukraine and condemning Russian aggression, while focusing on migration and social issues to keep their voters happy.

Even Le Pen has sometimes sought to distance herself from the AfD, raising the possibility that her party might abandon the ID grouping.

--With assistance from Cagan Koc, Donato Paolo Mancini and Iain Rogers.

(Adds comments from Ursula von der Leyen in the 17th paragraph. An earlier version of this story corrected the surname of a spokesperson in the 15th paragraph.)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.