This Ohio engineer is accused of Rwandan genocide. His family say he’s the victim

Ohio engineer Epa Bizimana was shocked last month when his aunt called him at work to say that her husband – the beloved uncle and mentor who’d inspired Bizimana’s own career – had been “taken.”

“I said, ‘Taken by who?’” the 40-year-old, tells The Independent. “She told me: ‘The FBI’.”

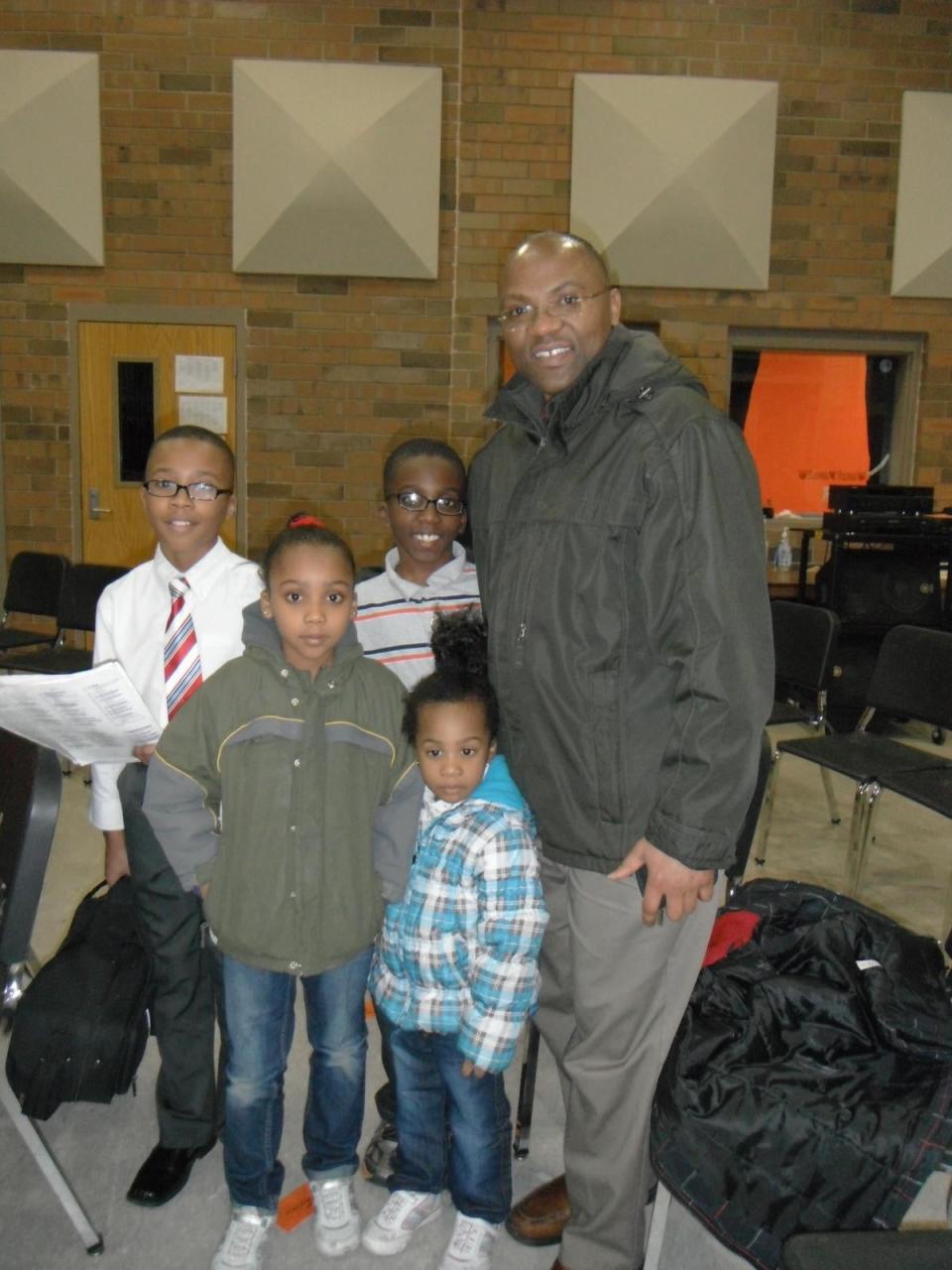

began a veritable nightmare for the Rwandan immigrant family. Bizimana’s uncle Eric Nshimiye — a long-time Goodyear engineer, Uniontown resident and proud father of four — had been arrested by federal authorities. The allegations were shocking: he was accused of perpetrating genocide during the very civil war and violence that drove the family from their home country.

The family patriarch was indicted days later on charges that included falsifying information, obstruction of justice and perjury – with witness accounts in court documents describing Nshimiye striking victims with a machete and nail-studded club.

He is due in court on Tuesday for an arraignment and possible detention hearing, during which he will plead not guilty, according to his lawyer.

“We just look forward to presenting the issue of detention to the court, so hopefully we’ll be able to get him released on bond, if not tomorrow, soon,” criminal defence lawyer Kurt Kerns tells The Independent.

Bizimana and throngs of other friends and family will be travelling by car, plane and train from Ohio, Texas, North Carolina and beyond to attend the Boston hearing and show their support. To say they were blindsided by the news would be an understatement; that disbelief spread throughout Nshimiye’s workplace and neighborhood where, by all accounts, he’d been a pillar of both communities for decades.

“Everybody was shocked,” says Bizimana, who adds he followed his uncle into engineering partly to “make him proud.”

“As they were reading the charges, and then even reading the newspaper, the articles, I kind of laughed a little bit – I said, you know, ‘Do these people know the person that they’re talking about?’ It’s actually laughable …I just wish it wasn’t so sad.”

Calling Nshimiye his “role model for as long as I can remember being alive,” Bizimana says: “Everyone who knows Eric does look up to him. He is a man of great character …and it’s very hard for us to be in this situation, because we know he is innocent.

“The past month or so has been hell,” he tells The Independent.

Their world fell apart after a Homeland Security investigator arrived on 11 March to Goodyear Tire & Rubber, where Nshimiye had worked for 23 years and was currently employed as the company’s principal engineer. He’d joined Goodyear five years after arriving in the US as a refugee from war-torn Rwanda.

The federal agent asked how Nshimiye had come to the United States and what his political affiliation had been prior to the Rwandan genocide, during which the ethnic minority Tutsis were systematically hunted down and killed by Hutu extremists. He asked if Nshimiye had been involved in raping or killing anyone during the bloodshed which left 800,000 dead.

Nshimiye “first responded by shaking his head, laughing nervously, and asking for a drink of water,” the investigator later wrote in court documents. “When I persisted by asking again, he falsely denied any involvement in raping or killing anyone during the genocide.”

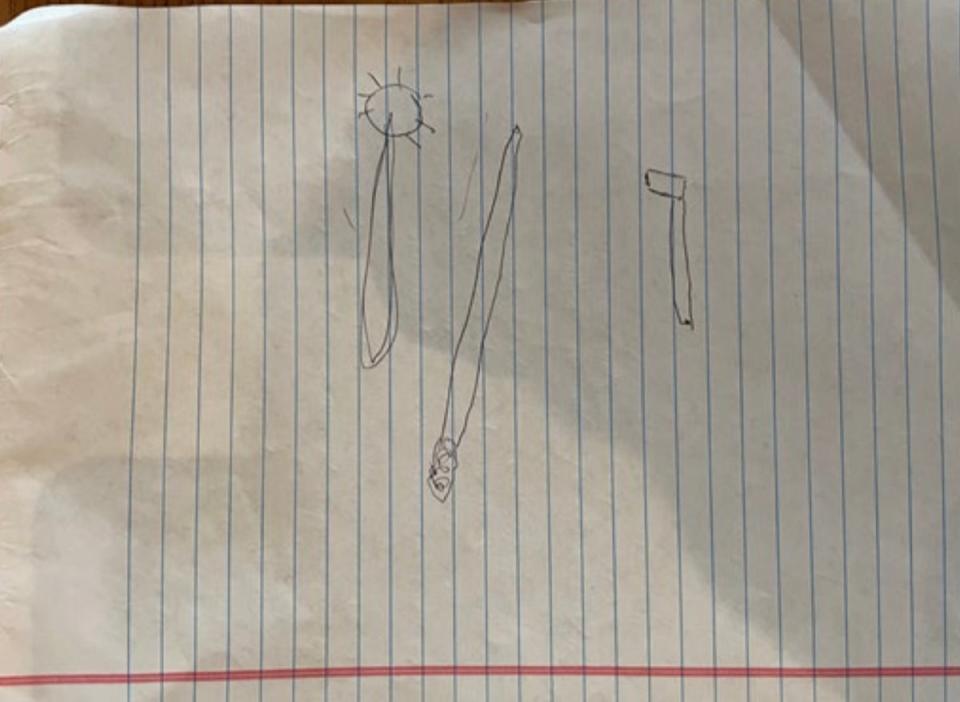

Investigators, however, had already compiled an avalanche of evidence indicating otherwise – and federal prosecutors charge that Nshimiye is instead a genocide perpetrator who’s been living a double life for decades. They believe he actively tracked down and pointed out Tutsis, identifying them for death, in addition to brutally murdering victims himself. In one horrifying instance, they allege he murdered a 14-year-old child using a machete and spiked club directly after killing the boy’s mother; court documents include drawn witness recreations of the weapons.

An ethnic Hutu, which constituted an 85 per cent majority in Rwanda in the early 1990s, Nshimiye enrolled as a medical student around 1991. He studied at the University of Rwanda in Butare, the intellectual and multi-cultural epicentre of the country at the time and also home of the university-affiliated hospital. He was still a student when the genocide began in 1994, according to documents.

The documents allege Nshimiye was participating in rallies and even undergoing weapons training as an active member of the Movement Revolutionaire National pour le Developpement, the ruling party of Hutus inciting the genocide, as well as its youth militia known as the Interahamwe. The student leader of the MRND in Butare during this time was a young man named Jean Leonard Teganya — who later moved to the US.

In 2017, Teganya was charged by the US government with fraudulently seeking immigration benefits by concealing his membership in the MRND party and his involvement in the genocide. During the 2019 trial, his old friend Nshimiye testified that neither he nor Teganya participated in the genocide, though the latter was convicted of two counts of immigration fraud and three counts of perjury.

Federal authorities now allege that Nshimiye falsely testified during Teganya’s trial and perjured himself when he denied his own membership in the MRND and Interahamwe.

“According to the charging documents, Nshimiye fled Rwanda in the summer of 1994, after an attacking Tutsi rebel group drove genocidaires into the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Homeland Security Investigations said in a release following his arrest last month.

“In 1995, Nshimiye made his way to Kenya where he allegedly lied to U.S. immigration officials to gain admission to the United States. Nshimiye emigrated to Ohio and, in subsequent years, allegedly continued to provide false information about his involvement in the Rwandan genocide to obtain lawful permanent residence and ultimately US citizenship. By allegedly concealing his crimes, Nshimiye has lived and worked in Ohio since 1995.”

After his initial disbelief upon receiving his aunt’s phone call, Bizimana says that, as he drove the hour or so from work to meet her, the 2019 testimony was the only thing he could think of that might involve the FBI in his uncle’s life.

There is a fear of this type of prosecution happening amongst many Rwandans living abroad, Nshimiye’s nephew says, and an aversion to involvement in trials or speaking up lest they be targeted by opposing power players. But Nshimiye’s testimony for his old classmate was mustered from “the courage to speak for a person who he believed should be spoken for.”

“One of the things that Eric does … he’s been running a mentoring programme,” Bizimana tells The Independent. “And one of the things that he actually appreciates the most is courage and fortitude and things like that.

“So when this came .. he probably looked at [the testimony] as something that he needs to do, something that he should do.”

While he and his relatives do not wish to discuss specifics in advance of court proceedings, he insists: “All of us are definitely fighting for him. We do believe that the truth is going to come out; the truth is going to prevail.”

Bizimana emphasizes they are a family of faith; devout Catholics, Nshimiye and his wife pray the rosary every night, and their oldest of their four children – a son who attended Harvard – felt a calling for the priesthood, Bizimana says.

He and the wider family issued a defiant “statement regarding baseless accusations and assassination of character.”

“The United Nations International Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in Arusha, Tanzania to account for all principal orchestrators of the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, and Eric Nshimiye’s name never appeared,” continued the statement, posted to a family website dedicated to clearing Nshimiye. “The Human Rights Watch drafted intensive investigative reports at the time as to those responsible. Eric’s name never appeared.

“The local Gacaca courts - a system of transitional justice in Rwanda following the genocide - were established and for decades after the genocide, Eric’s good name went unassailed. Only after he agreed to act as a defense witness did these false accusations arise … Our family vehemently denies all allegations brought against Eric and asserts his complete innocence.

“He is a beloved active figure in the community, a devoted husband and father, and a man of deep faith as evident in every aspect of his life. We attest to his moral integrity and dismiss the charges against him as incompatible with his character and beliefs, as those who know him would agree.”

Teganya, for his part, was sentenced in 2019 to 97 months in prison, after which he will face removal proceedings. The charge against Nshimiye of falsifying, concealing and covering up a material fact by trick, scheme or device provides for a sentence of up to five years in prison, three years of supervised release and a fine of up to $250,000. The charge of obstruction of justice provides for a sentence up to 10 years in prison and perjury provides for a sentence of up to five years.

The Department of Justice declined to comment on the case when contacted by The Independent.

As Nshimiye’s family continue to protest his innocence, the family are hoping this week that, “obviously, we want to come back home with Eric with us,” Bizimana says.

“We want to make sure that he’s well, he is healthy, obviously,” he says. “At the same time, we want to continue this fight for truth – not just for Eric, but we really want to make sure that Eric is the last person that this happens to … we just all put our heads together, pray and figure out what we can do.”