Presidential greatness is rarely fixed in stone – changing attitudes on racial injustice and leadership qualities lead to dramatic shifts

Every American president has landed in the history books. And historians’ assessments of their performance have been generally consistent over time. But some presidents’ rankings have changed as the nation – and historians themselves – reassessed the country’s values and priorities.

Historians have been ranking presidents in surveys since Arthur Schlesinger Sr.’s first such study appeared in Life magazine in 1948. The results of that survey categorized Presidents Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson as “great.”

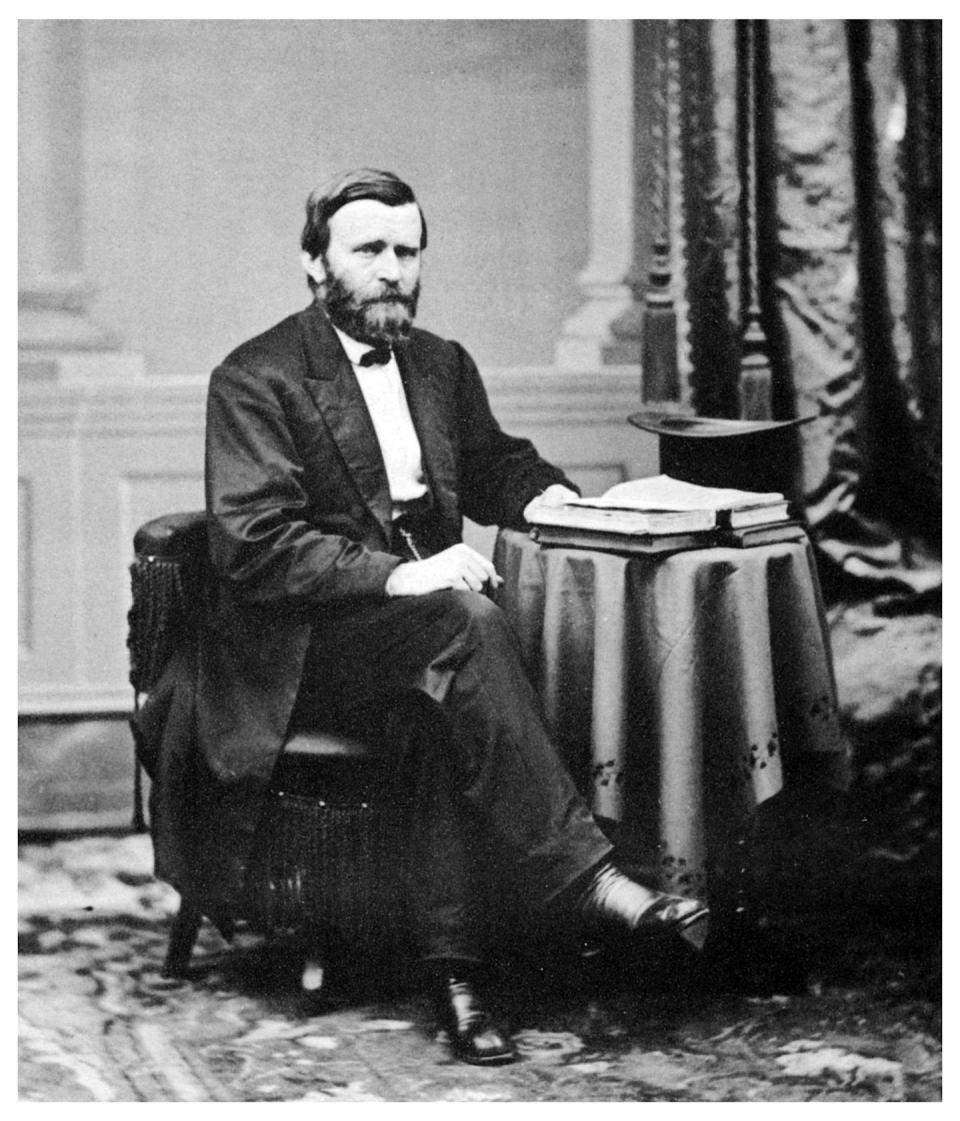

At the other end of the ranking, Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Warren Harding were labeled “failure.”

There have been numerous surveys ranking presidents since then, including a 1962 survey by Arthur Schlesinger Jr., which showed Jackson dropping into a “near great” category.

Changing views shift rankings

While the surveys point to Americans’ evolving social attitudes, with implications for our electoral politics and governance, they don’t always ask historians the same questions. Some simply ask them to rank presidents. Others ask them to also judge specific aspects of leadership, such as economic policy or international diplomacy.

Despite the relative stability of the ratings across surveys – especially at the top, where Lincoln, Washington and Roosevelt consistently hold sway – there have been some dramatic changes. C-SPAN’s four surveys on presidential leadership, for example, show some shifts in historians’ ranking of presidents over time.

Since 2000, the cable network has polled prominent historians every time there has been a change in administrations. So, C-SPAN conducted surveys in 2009, 2017 and 2021 as well.

The surveys offer not only an overall ranking of presidents, but also rankings in each of the following 10 categories: public persuasion, crisis leadership, economic management, moral authority, international relations, administrative skills, relations with Congress, vision and agenda setting, pursuance of equal justice for all, and performance within the context of the times.

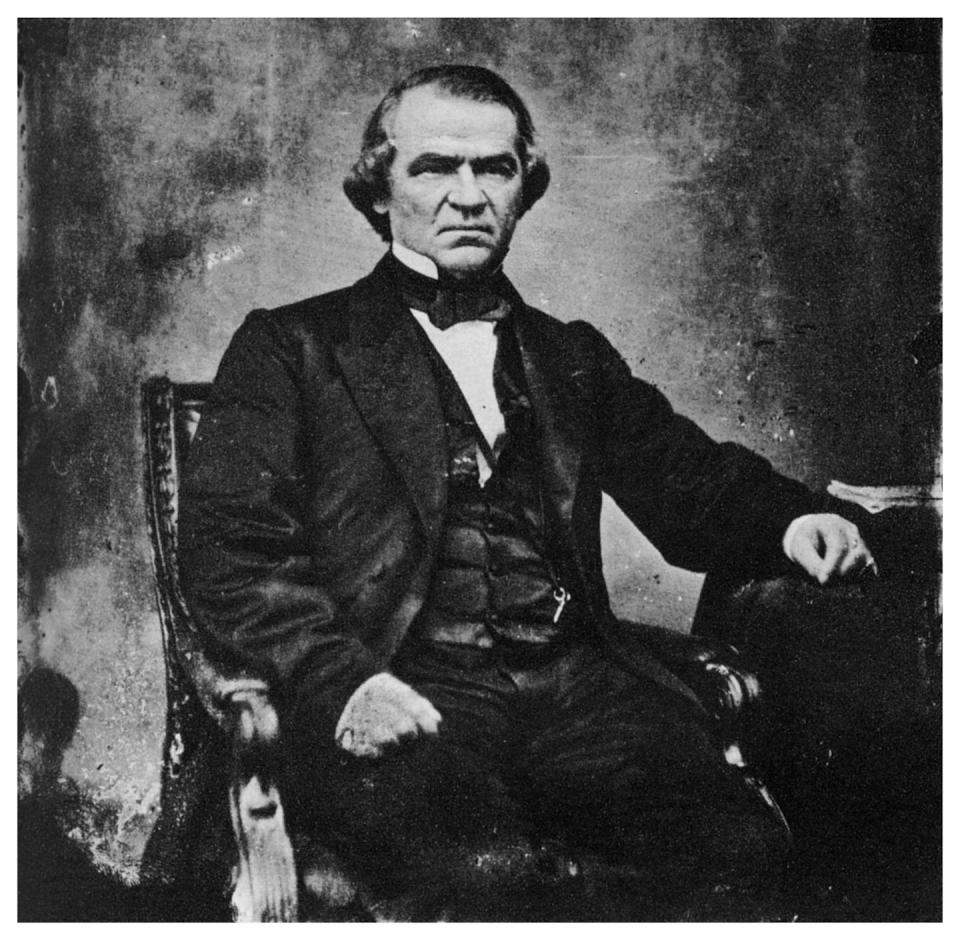

While Lincoln has ranked at the top of each survey, the two presidents who served right before him – Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, both sympathetic to slavery – and his immediate successor, white supremacist Andrew Johnson, have consistently ranked at the bottom. Donald Trump debuted in C-SPAN’s 2021 survey near the bottom. He was ranked 41st of 45 presidents.

What is a good leader?

As a social psychologist and leadership scholar at the University of Richmond’s Jepson School of Leadership Studies, with long-standing interests in presidential leadership, I believe these surveys can be best understood in terms of psychologist Dean Keith Simonton’s model of evaluating presidents.

He maintains that historians generally view leaders, including presidents, positively to the extent that they fit a deeply ingrained image of someone who is strong, active and good. And that image comes to mind when they think of attributes and events linked to a president that suggest he was a good leader. Examples include how long he served, whether he was a war hero and whether he was assassinated, and in that sense, was a martyr.

On the other hand, historians also easily recall scandals, such as Richard Nixon’s Watergate and Harding’s Teapot Dome. These detract from these presidents’ “good” image, as evidenced by Nixon’s and Harding’s rankings of 31st and 37th, respectively, in C-SPAN’s 2021 survey.

Race matters

In recent years, presidents’ positions on race and racism have been important factors in historians’ evaluations of their records. For example, Wilson’s rather startling efforts to segregate federal offices and the military are becoming more widely known as scholars explore that aspect of his presidency.

His actions in that regard may overshadow his international idealism, which favored morality over materialism and has been viewed positively. He is no longer considered one of our “great” presidents. In Schlesinger Sr.’s 1948 survey, he ranked fourth of 29 presidents. But in 2021, historians ranked him 13th of 45 for C-SPAN.

Jackson dropped the most in C-SPAN’s surveys, from 13th in 2000 to 22nd in 2021. His commitment to Indian removal from Southern and Midwestern states, not unique for the time, and the resulting Trail of Tears – the forced and violent relocation of Native Americans from their homelands – are important topics in today’s political discussions.

Several other presidents who lost ground, including James Polk, Zachary Taylor, Rutherford B. Hayes and Grover Cleveland, were associated with efforts to extend slavery or with failure to protect African Americans following Reconstruction.

Then there is the case of Grant. Ranked at the bottom as a failure in the mid-20th century, he had the largest ranking change of any president in the C-SPAN surveys. He jumped 13 places from 33rd in 2000 to 20th in 2021. He had already moved up from second-to-last place in the 1948 and 1962 Schlesinger surveys to somewhere in the bottom quartile in 2000, to a position in 2021 where more presidents ranked worse than he did.

The 2021 C-SPAN survey ranks Grant sixth on “pursued equal justice for all,” behind only Lincoln, Lyndon Johnson, Barack Obama, Harry Truman and Jimmy Carter. Given the centrality of equal justice, which may overshadow whatever connection Grant may have had to scandals in his administration, such as Crédit Mobilier and the Whiskey Ring, Grant rises in historians’ overall evaluation.

Moral authority

This all suggests historians have quite simple ways of evaluating presidents. We have an image of the ideal leader. Just a few pieces of information relating to that ideal make a big difference in whether we view presidents as fitting or not fitting that image. This is particularly true of our perception of how good they were. Presidents’ moral commitments speak loudly to whether or not we view them as good.

Interestingly, on the quality of “moral authority” in the C-SPAN surveys from 2000 to 2021, Grant’s ranking rose 14 rungs, from 31st to 17th, even more than it did on “pursued equal justice for all,” where it rose 12 rungs, from 18th to sixth. Wilson and Jackson dropped 13 and 18 places, respectively, on “moral authority.”

Clearly, moral judgments loom large in historians’ assessments of presidential leadership.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: George R. Goethals, University of Richmond

Read more:

Measuring a president’s first 100 days goes back to the New Deal

All American presidents have lied – the question is why and when

George R. Goethals received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health from 1971-1983. He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association, the Society of Experimental Social Psychology, and the Association for Psychological Science and a member of the Society of Personality and Social Psychology and the International Leadership Association. Dr. Goethals met Dean Keith Simonton at a professional meeting.