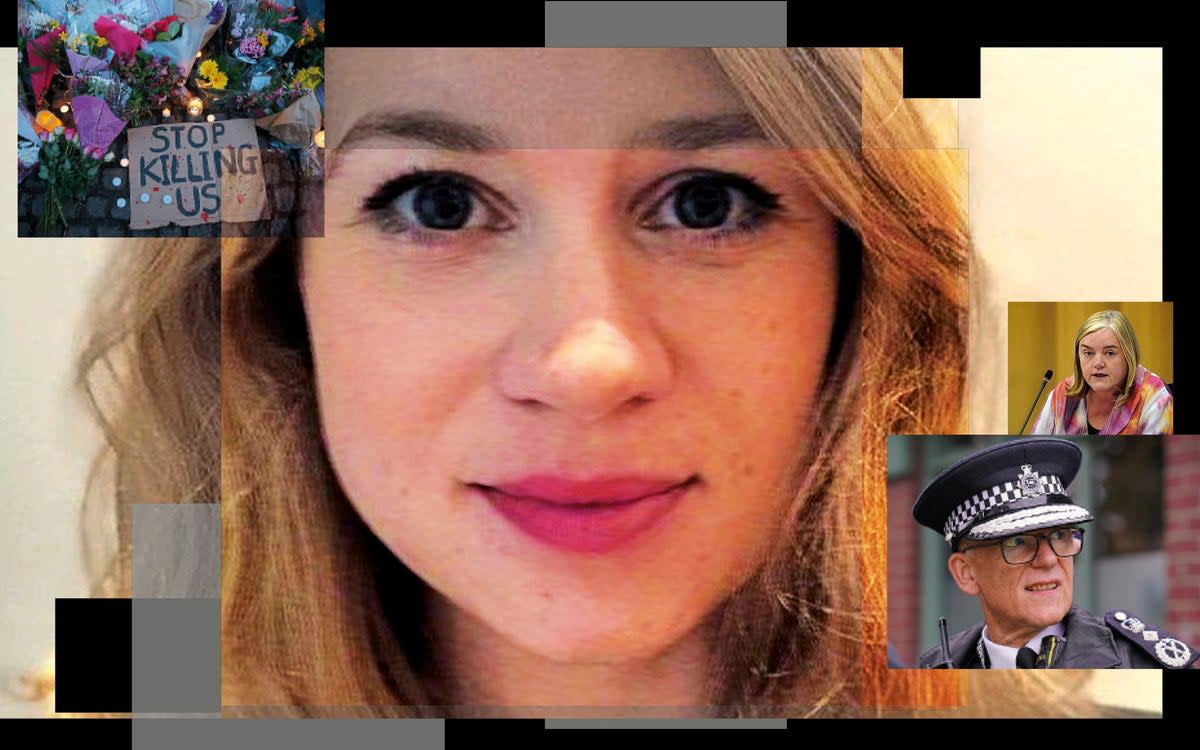

'Three years after Sarah Everard's murder, we feel more afraid — not less'

Arabella James still has just as many questions as she did in those first, unforgettable few days after Sarah Everard’s death three years ago, when news that she’d been murdered by a police officer shocked the nation and galvanised a movement on women’s safety.

The south-west Londoner and her housemates still live within a mile of the street in Clapham in which Everard, a 33-year-old Durham graduate and marketing executive, was abducted, raped and killed by an off-duty Metropolitan Police constable in a series of shocking events set to be retold in a bombshell BBC documentary next Tuesday.

James, 29, thinks about the story often, whenever she’s walking at night or tracking her housemates home on her iPhone’s Find My feature. If a police officer stops and asks her to get in his car, what are her options? Will carrying a rape alarm still be the reality for women like her living in London in 30 years’ time? And what will it take to feel like the police are taking women’s safety seriously, then, if not the brutal murder of an innocent young woman by one of their own?

“It’s hard to imagine a news story that could shock us more than what happened to Sarah,” says James, an executive assistant working in the city. “What’s even more shocking is how little it feels has been done since then. The mayor is supposed to be helping make us feel safer, but instead he seems to be spending his money on renaming Tube lines... It’s getting boring now: praying for summer to come around so we feel safer. I think I can speak for all my female friends when I say I feel just as afraid walking home at night as we did three years ago... if not more so.”

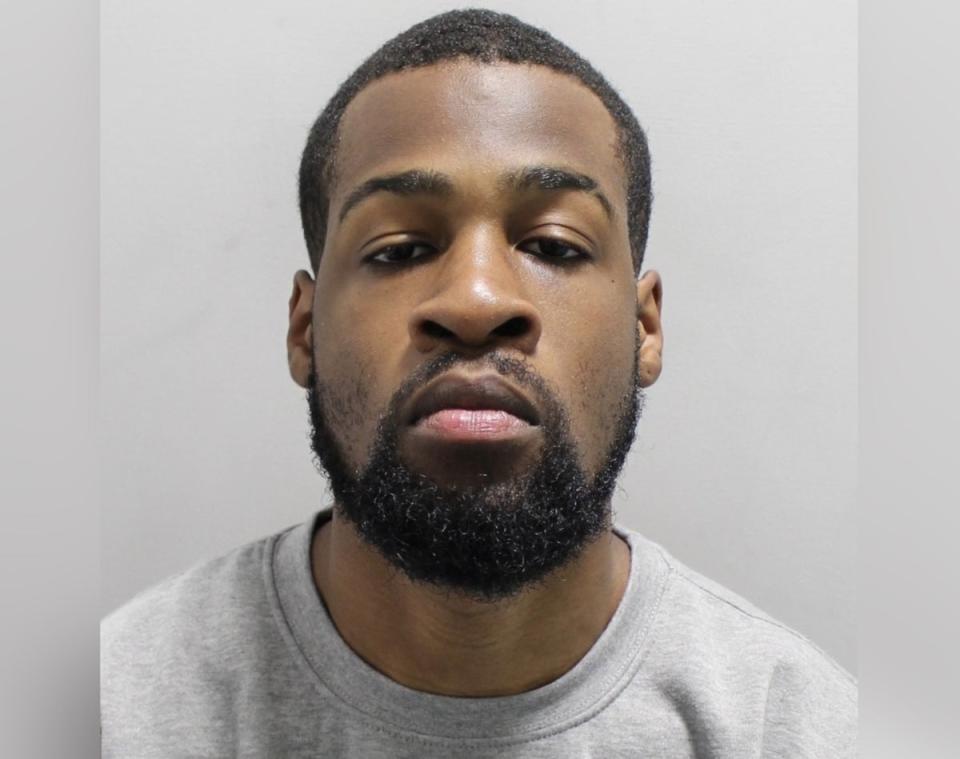

James and her friends are hardly alone in their fears. This Sunday, March 3, marks three years since Everard’s brutal murder and questions are naturally being asked about what, if anything, has changed for women’s public safety. "We're not learning, we're not changing things,” says Lisa Squire, whose daughter Libby was abducted and killed in Hull in 2019 amid reports of a continued stream of violence against women since Everard’s killing — the murders of Sabina Nessa, Zara Aleena, Ashling Murphy, to name a few — and calls for greater vetting of police recruits and work to prevent repeat offenders (Couzens reportedly exposed himself in public, twice, hours before he murdered Everard). “Something has gone horrifically wrong with the way police officers are recruited. Brutes are permitted to join their ranks,” former cabinet minister Nadine Dorries said last week following news that Cliff Mitchell — a serving PC who was appointed after Everard’s murder — had been found guilty of kidnap and multiple rapes, including three against a child, despite having been accused of raping a child before joining the force.

The Met insists it is listening to the fears of women and girls it’s let down; that it acknowledges Couzens was more than one bad apple and is determined to improve its service with a practical and cultural shift. “We’re using innovative tactics to target predatory men who pose the greatest risk, creating safer spaces for women and girls to enjoy without fear and embedding a culture across the Met where tackling violence against them is a priority,” says Deputy Assistant Commissioner Helen Millichap, its lead for Violence Against Women and Girls.

New tactics include a new V100 project to identify the most dangerous sexual predators (39 men have been arrested and 17 convicted since it launched in July), telephone data analysis to better identify stalkers, and a rapid video response pilot for responding to domestic abuse reports within minutes. So far, rape charges are up 41 per cent on last year, stalking protection orders have doubled and new safe spaces have been introduced at “high risk locations” such as festivals and bars.

I feel just as afraid as three years ago. It’s getting boring now: praying for summer to come around so we feel safer

Arabella James, 29, an executive assistant living less than a mile from where Everard was abducted in 2021

But campaigners say it’s not enough — a damning report into Couzens’ history was released today, concluding that the Met and other forces ignored a succession of “red flags” about his predatory offending that should have stopped him being in the police. Among the alleged crimes by Couzens were a knifepoint kidnapping in north London in 2015, two rapes in the capital, and an “alleged sexual assault against a child (barely in her teens” before he joined Kent Police as a volunteer officer in 2006.

At least 154 UK police officers have been convicted of crimes since Couzens’ eventual arrest in 2021. “Something is horribly wrong,” Laura Richards, the former head of New Scotland Yard’s Sexual Offences Section, said following the Mitchell news last month. And even staff within the Met have agreed the culture shift their bosses speak about is lacking on the ground. Last week, Sam*, a current officer in the Met, told the Standard he still witnesses that testosterone-fuelled “alpha male” culture every day — rude language to describe women, brags about sleeping with junior colleagues, victim blaming — and believes any talk of a culture change by senior staff is “bull***”. “How would the senior leadership team know what the Met culture is?” he asked. “The only time we see them is when they’re on BBC News.”

Police failings aren’t the only concern fuelling women’s fears that women are feel less safe than they were before the events of March 3, 2021. “It’s impossible to say we’ve seen any visible improvements in practical resourcing,” says Natasha Walter, a feminist writer and founder of the charity Women for Refugee Women, pointing to London’s continuing court backlogs and cuts to public services like survivor support groups and street lighting. Just last month, Havering London Borough Council announced it was to dim thousands of street lights at night in a bid to tighten budgets — a “backwards step” that campaigners called just another example of women’s safety continuing to be “an afterthought”. Others point to the frightening rise in self-professed “misogynist” influencers like Andrew Tate, believed to have fuelled a turn against feminism among young men. “My son’s a feminist, but this real backlash to women’s equality is really, really worrying,” says Walter.

So what lessons have been learnt since Everard’s murder, if any? What can be done to rebuild trust in the police and prevent atrocities like the Everard case from happening again? And has women’s safety really got worse, as insiders suggest?

That depends who you ask and where you look, says Suzanne Jacob, CEO of domestic abuse charity SafeLives. Everard’s story sparked a collective sense of grief, fear and rage and gave many women a platform to share their everyday experiences of harassment and abuse — often for the first time. There were other positives, too, like the subsequent Everyone’s Invited movement in schools across the country; businesses investing in employee safety and self-defence classes; and pledges by the police and other authorities to address the issue at its root. “This is a moment for men to ask why this keeps happening, and why the common denominator, over and over, is a man who felt entitled to take something that didn’t belong to him,” Jacob said at the time.

The resulting movement was quickly nicknamed #ReclaimTheStreets to reflect the sense of empowerment many women felt by the national conversation on safety — but do women actually feel empowered, as many hoped? “We’re going forwards and backwards at the same time,” Jacob explains, three years on. “Forwards, in that some police forces including the Met Police have started to recognise the scale of the problem. Policing oversight bodies such as the National Police Chiefs Council are pressing ahead with change on issues like vetting, operational responses to VAWG, and culture change. Backwards, though, because we know this commitment to change isn’t shared by all officers, and is being actively resisted in some places. When you have progress, so you have a backlash.”

Rebecca Goshawk, head of partnerships and public affairs at domestic abuse organisation Solace Women’s Aid, agrees. She believes women’s safety online has gone backwards thanks to the rise in nonconsensual images and the proliferation of deepfakes — threats that spill over into the real world. Offline, the threats might not be as new but fear of them is just as fresh today as they were in the weeks after Everard’s murder, if not more so. “Women cannot and will not forget,” Woman’s Hour host Emma Barnett said ahead of the third anniversary of Everard’s murder. “I am certainly more vigilant and aware of my surroundings since [Everard’s murder],” says Natasha Tiwari, a psychologist and founder of education consultancy The Veda Group.

We know this commitment to change isn’t shared by all officers. When you have progress, you also have backlash

Suzanne Jacob, CEO of domestic abuse charity SafeLives

Dene Josham, Angelina Jolie’s former bodyguard and co-founder of Streetwise Defence, which runs street safety workshops for staff at corporates including Vita Coco and Infosys Consulting, believes Tiwari speaks for most women in the capital. “Women are definitely more worried [than they were before Everard’s murder],” he says. “They don’t feel safe travelling alone in London, especially on public transport and especially at night.”

Josham says he sees the same themes come up again and again in his workshops: that there’s still a lack of visible police patrols across the capital; that women fear they’re not strong enough to defend themselves; that they still don’t know what their options are if they find themselves in Everard’s situation of being stopped by a police officer (the Met says anyone who wishes to check the identity of a police officer should call 999). “I [walked home alone at night] once after Everard’s murder and a police car was driving towards me and I realised I was more not less scared,” says Thalia Pellegrini, 48, a nutritionist and TV presenter from north London. “It was a sad realisation. Now, I just don’t do it at all.”

Goshawk feels sad to think this is still the case, three years after an atrocity that people across the world hoped would be a turning point. She welcomes efforts by authorities like the police and the mayor’s office, which launched its Women’s Night Safety Charter in December, as well as the stream of tech companies and volunteer organisations joining the crusade. Platforms like Citymapper have brought in Walk Less features to maximise time on public transport. Hotlines like Strut Safe (03333350026) have been set up to talk to victims as they’re walking home. And apps like Epowar promise to send alerts if victims are attacked.

But small, individual efforts like this are not enough — and still place the responsibility on women to change their behaviour, says Goshawk. “Women are fed up of key-clutching, we’re fed up of rape alarms, and we’re exhausted with texting our friends to check they’ve got home ok,” says Eliza, a primary school teacher from Tooting, who believes women’s text-me-when-you-get-home culture still feels like the most reliable safety mechanisms she and her female friends use day-to-day.

“It’s one of the biggest things that separates my male and female friends’ London existence,” she continues. “Men get home from the pub, brush their teeth and go straight to bed; women brush their teeth and still up sit scrolling Instagram until they get that WhatsApp saying ‘Home x’. It might not do much to help if the worst does happen to one of us, but the reality is we still feel responsible for each other’s safety because we can’t trust the authorities to be.”

For Goshawk, the conclusions of Baroness Casey’s 2023 report into the Met — that the force is broken and rotten, that public trust in it has collapsed, that it’s guilty of institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia — only added to the need for attention needs to move away from women’s daily calculations and compromises towards tackling the problem at its root: the beliefs and attitudes of perpetrators, largely men.

Women are fed up of key-clutching, we’re fed up of rape alarms, and we’re exhausted with texting our friends to check they’ve got home ok

Eliza, a primary school teacher from Tooting

So what can be done? Stricter sentences, greater reporting of crimes, and more specialist training for officers in tackling violence against women and girls, if you ask campaigners like Squire, Goshawk and Jacob. Everard’s case confirmed the links between more minor acts of sexual offence such as flashing, and how they can escalate to the worst possible forms such as rape and even murder, and statistics show that 25 per cent of offenders go on to reoffend. “It does feel like, not just me, but any victim in these circumstances is a guinea pig,” Rhianon Bragg, who survived being stalked by her ex and held at gunpoint for eight hours, recently told Woman’s Hour of the news that her ex is to be set free after just four-and-a-half years in jail.

The Met says it recognises there is more to do but is taking steps to address this, launching a 10-point Violence Against Women and Girls Action Plan in 2022, which will see an extra 500 officers and staff dedicated to identifying offenders and supporting victims.

But the fact that the perpetrator in Everard’s case was a member of the Met’s own workforce has inevitably turned the spotlight towards its internal culture. A recent YouGov poll carried out for the domestic abuse charity Refuge found that 53 per cent of women feel that the police have made little or no progress in addressing problems of sexism and misogyny among officers over the past year. The replacement of the Met’s first female commissioner Cressida Dick with another man, Sir Mark Rowley, hasn’t helped this. Nor have several revelations that have come to light since Everard’s murder, such as the Met constables who shared images of murdered sisters Nichole Smallman and Bibaa Henry on WhatsApp groups with their mates, and the swapping of violent and sexist messages between offices at the Met’s Charing Cross outpost.

“The problem is you can’t legislate culture change,” says Sam*, a current officer with the Met. He believes the Met’s so-called “toxic” internal culture has only worsened since Everard’s case because male staff became defensive and concerned for their own welfare, rather than for victims. “In the 18 months immediately [after the Everard case], I know loads of male officers who’d say they wouldn’t speak to female officers unless they spoke first, because it’s wasn’t worth the risk,” he recalls. “The senior leadership team can speak as much about the culture as my ice cream man can. They know they can’t change the culture; they have no interest in changing it properly; what they do have an interest in is looking like they’re changing it.”

Sam says he is hopeful that the culture will slowly change over the next 10 or 20 years, as older members of staff retire out of the service and younger, hopefully more culturally-sensitive recruits move in. The Met doesn’t exist in a vacuum, after all — it reflects society. “It’s a revolving door of 35,000 or so individuals, so naturally policing culture will change as society changes.”

Education is the most effective way to bring about this societal change, most agree — but it’s complicated. After Everard’s murder, there was an initial leaning-in by young people, their parents and educators: schools and universities introduced workshops on safety and consent, and the Everyone’s Invited movement encouraged victims of sexual assault to speak about their experiences.

A counter movement is operating really successfully to tell boys and men that they’re being victimised, and that better rights for women means harm to men

Suzanne Jacob, CEO of domestic abuse charity SafeLives

But since then the conversation among young people appears to have taken a more sinister turn. Last month, research by King’s College London’s Policy Institute and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership found that boys and young men from Generation-Z are more likely than older baby boomers to believe that feminism has done more harm than good — a “new and unusual generational pattern” that many put down to the rise of toxic masculinity poster boys like Andrew Tate (a fifth of those surveyed claimed to look on him favourably).

Others disagree, saying “Tate is the symptom, not the cause” of a growing problem; that we need to consider why Gen-Z might feel it’s harder to be a man than a woman. Do they feel confused? Attacked? Threatened? “Where survivors of violence are speaking out about what has happened and advocating for change, a counter movement is operating really successfully to tell boys and men that they’re being victimised, and that better rights for women means harm to men,” says Jacob.

Starting a conversation — as we did in those weeks after the Sarah Everard tragedy — is the answer again, in her view. She welcomes recent campaigns by the Mayor of London and the Home Office aiming to start a direct conversation with boys and men, and supports Labour’s plan to train young male influencers to provide a “powerful counterbalance” to the negative impact of misogynists like Tate.

Can we be hopeful for women’s safety, then, three years on? For Jacob there’s no question. “I have hope every time I see a woman stand up and talk about what’s she lived through and the change she wants to see. We’re not going back,” she says, firmly. Walter is less confident. “I don’t really feel hopeful at the moment, but that doesn’t stop me being active,” she says. “That’s the conversation I’ve been having a lot among the feminist movement: we can’t wait for hope to move us to act. We have to act and hope it makes space for hope.”

In ten years, yes, Walter has faith safety will have changed for the better. But a decade is a long time, she says — and that’s the thing about safety: “we don’t have time to waste.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities