Why Nigel Farage’s Reform is a company and not a party - and what that means

Nigel Farage has announced he will become the new leader of Reform UK and that he will stand for election in Clacton, Essex.

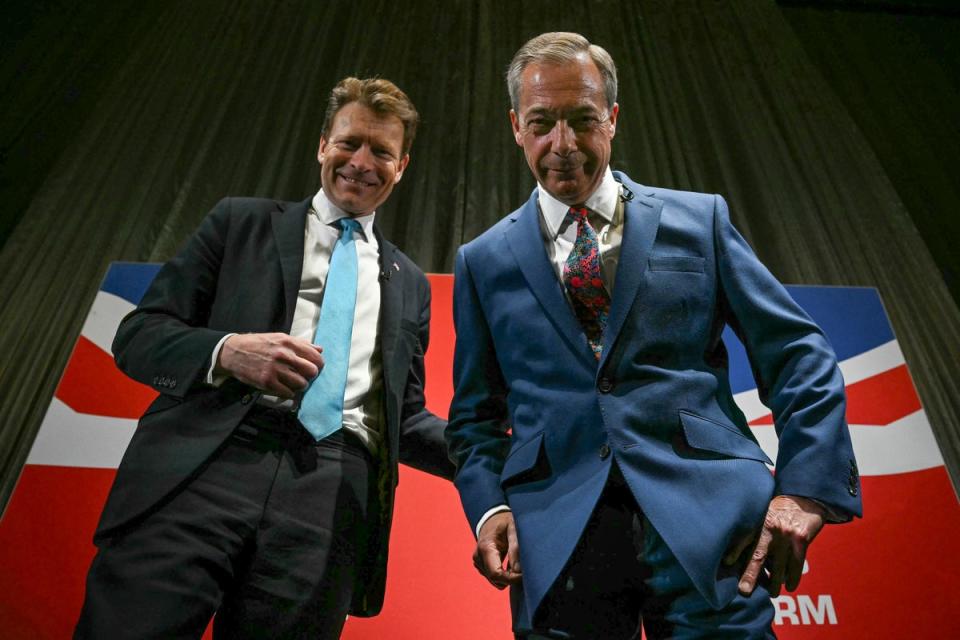

But there was one burning question: who had appointed him? The answer was no one, really - or possibly former leader Richard Tice.

As an “entrepreneurial political start-up” with Mr Farage as the company’s director and majority shareholder, there was no internal leadership election, like Labour or the Conservative Party.

Mr Farage claimed Reform UK would “democratise over time” after he was accused of running a “one-man dictatorship” by broadcasters.

With the party set to contest constituencies up and down the country on 4 July, The Independent takes a look at the company’s unusual structure and how it differs to other parties.

What is Reform UK?

Reform UK Party Limited was founded in November 2018 as an “entrepreneurial political start-up”. Mr Farage owns 53 per cent of the company.

It says it is a UK national political party “offering common-sense policies on immigration, the cost of living, energy and national sovereignty,” according to its website.

Mr Farage is able to remove Mr Tice as director, and take the decision to unilaterally dissolve the organisation, making him the party’s ultimate decision-maker.

Meanwhile, Mr Tice has a minority holding of around one-third of shares, and chief executive Paul Oakden and party treasurer Mehrtash A’zami each hold less than 7 per cent.

How is it different to other political parties?

British political parties are traditionally formed as unincorporated associations composed of a membership, rather than established as corporate entities.

Rules are usually set out in a written constitution, while party affairs are handled by a committee chosen by members - like that of Labour or the Conservatives.

However, all political parties, including Reform, are required to register with the Electoral Commission and comply with obligations under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA).

Reform’s co-deputy leader has previously said the structure allowed the organisation to “cut through” as an “insurgent party” without the possibility of factionalism which can plague other parties.

How will it affect the election?

As it is registered with the electoral commission, Reform UK is allowed to run for election like other major political parties on 4 July.

But with 115,00 paying supporters with no voting power to influence policy, Reform has admitted its structure might not be sustainable in the long-term - something that could change after this year’s election.